Compared to all the other giant planets in the solar system, Uranus seems the least distinguished. It is not as beautiful as Neptune, it does not have the same impressive rings as Saturn or the same impressive moons as Jupiter.

But this is a very misleading impression. In reality, Uranus is one of the most unusual and intriguing planets in the solar system which has so many mysteries still waiting to be revealed. It is our subject for today.

The Great Expansion of the Solar System

The apparent magnitude of Uranus ranges from 5.4 to 6.0. This means that under ideal conditions, it can be seen with the naked eye as a very faint star. In the past, before the Industrial Revolution, when the earth’s atmosphere was much cleaner and there was no light pollution in the sky, this was much easier to do than it is now.

There is no doubt that many people have seen Uranus throughout history, but it was simply too dim for anyone to suspect it was anything more than an ordinary star. Some scientists believe that the small star included by Hipparchus in his famous star catalog was in fact Uranus. The first confirmed observation of the planet dates back to 1690, when astronomer John Flamsteed observed it at least six times through his telescope.

This begs the logical question: why is Flamsteed not considered the discoverer of Uranus? The fact is that although the astronomer observed Uranus, he did not recognize it as a planet and registered it as star 34 in the constellation Taurus. This could have been a factor both of the insufficient magnifying power of his telescope and the fact that scientists of that era were not really searching for planets. The solar system was believed to end at Saturn.

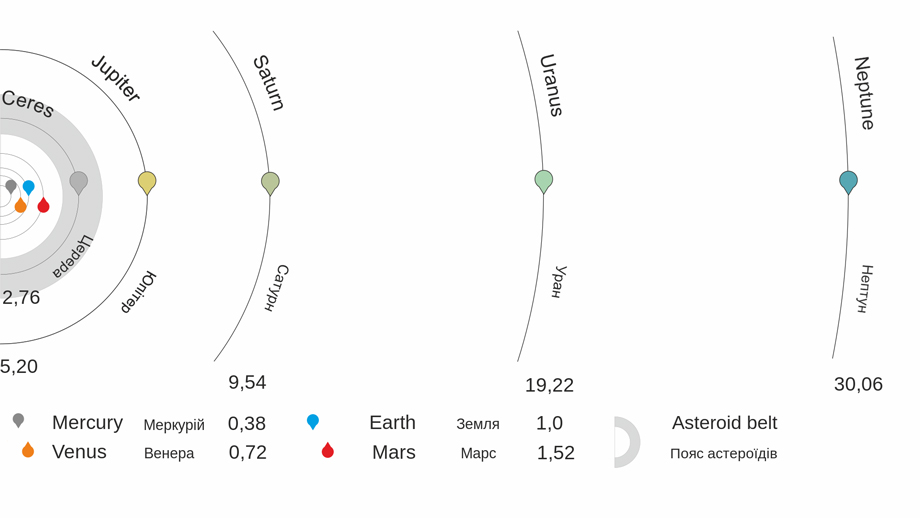

Subsequently, several more astronomers would spot Uranus, but none of them recognized its true nature. Everything changed only in 1781, when the planet was observed by William Herschel. He realized that it was not a star, but at the same time, that he had initially misclassified the object as a comet. To a certain extent, this demonstrates the power of inertia in the scientific thinking of that era. Only after a series of subsequent observations, carried out both by Herschel himself and by other astronomers, did they come to the conclusion that it was not a comet, but a previously unknown planet. Thanks to this discovery, the Solar system almost doubled in size – after all, if Saturn is approximately 9.5 AU (1.43 billion km) from the Sun, then the orbit of Uranus lies at a distance of 19.2 AU (2.87 billion km).

However, problems arose with choosing a name for the new planet. Herschel himself proposed calling it “George’s Star” in honor of his patron, King George III of England. But the astronomical community as a whole reacted very coolly to such an initiative. French astronomer Joseph Lalande proposed naming the planet in honor of its discoverer – “Herschel.” The options “Astraea” and “Neptune” were also considered. But in the end, the name “Uranus” was assigned to the seventh planet. The name “George’s Star” proposed by Herschel was used only in Great Britain, but by the middle of the 19th century they, too, had switched to using Uranus.

“Rolling” planet

By the time of Uranus’s discovery, the presence of moons around other planets no longer seemed unusual. Astronomers thus began searching for Uranus’ companions. Their first success came as early as 1787, when the planet’s two largest moons, Titania and Oberon, were identified. Ariel and Umbriel followed in 1851.

Uranus was also used as a kind of test subject for the then-new law of universal gravitation. Scientists were interested in whether the law held for planets located at a great distance from the Sun. Decades of observations have shown that Uranus is “willful” and does not move across the sky exactly as it should according to theory. This gave astronomers the idea that there was another as yet unknown planet in the solar system whose gravity was affecting the orbit of Uranus – and they began to look for it.

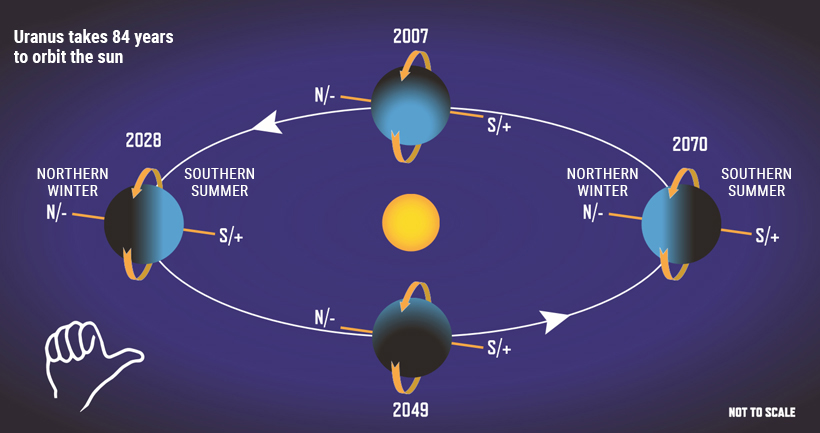

Subsequent observations revealed another unusual feature of the planet. It turned out that the plane of Uranus’s equator is inclined to the plane of its orbit at an angle of over 90 degrees. That is, the planet rotates retrograde, lying on its side slightly upside down. Therefore, if other planets are usually compared to spinning tops, then Uranus is more like a rolling ball.

Because of this feature, the planet has a very unusual seasonal pattern. The rapid change of day and night occurs only at the equator, while the Sun there is located very low above the horizon (as in the Earth’s polar latitudes). As for the poles, one of them is in darkness every 42 Earth years, while the other is constantly illuminated by the Sun for 42 years. Then they change places.

As for the physical characteristics of the planet, it was possible to establish that Uranus is four times larger and 14.5 times more massive than the Earth. This makes it the fourth most massive planet in the solar system. Before the start of the space age, it was believed that Uranus was similar in its internal structure to Jupiter and Saturn and was mainly composed of hydrogen and helium.

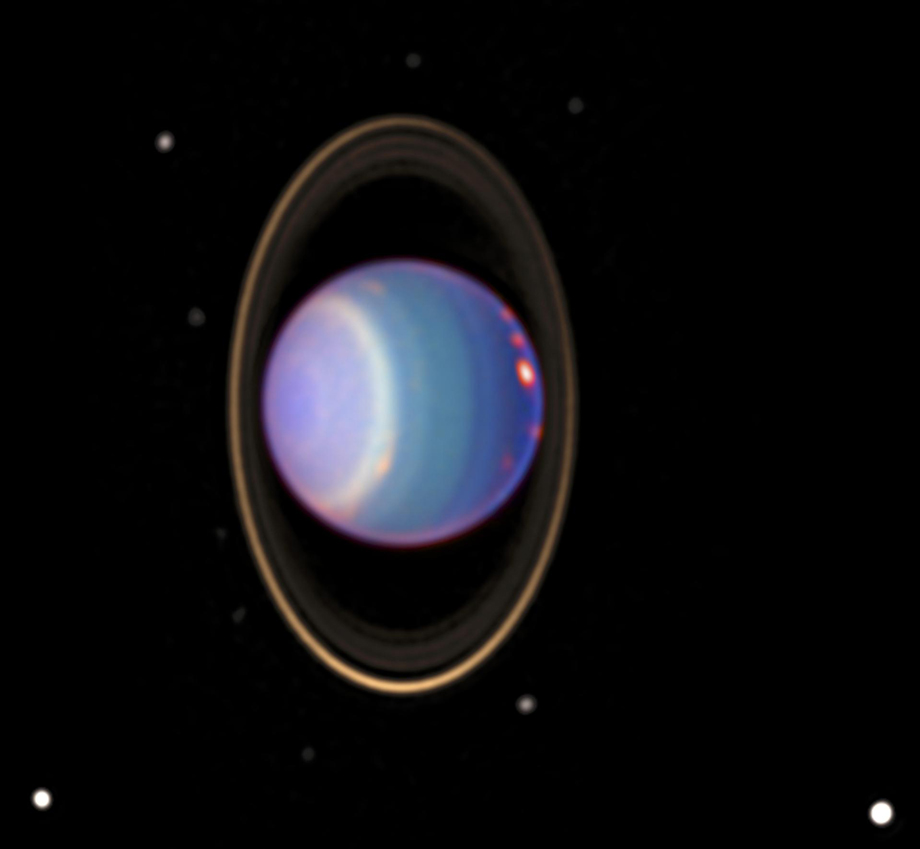

The last important discovery made before Uranus was visited by an earthly messenger occurred in 1977. It turned out that the planet has rings. This was actually an accidental discovery. Astronomers were observing the occultation of Uranus by a background star in order to study its atmosphere. However, shortly before and immediately after the occultation, they detected a decrease in the star’s brightness, indicating that the planet has rings. In this regard, it is curious that back in 1789, William Herschel announced that he had observed rings around Uranus. However, given their lackluster quality, most scientists still chalk this statement up to scientific error.

Voyager 2 visit

To this day, only one spacecraft has visited Uranus. This was done by Voyager 2 in 1986, which carried out a close flyby of the seventh planet. The visit might not even have happened. Initially, Voyager 2’s flight plan only included visiting Jupiter and Saturn. Fortunately, NASA wisely ensured that the flight plan also included the possibility of subsequently traveling to Uranus and Neptune. And after its launch, NASA managed to secure the allocation of additional funding, which made it possible to continue the device’s journey.

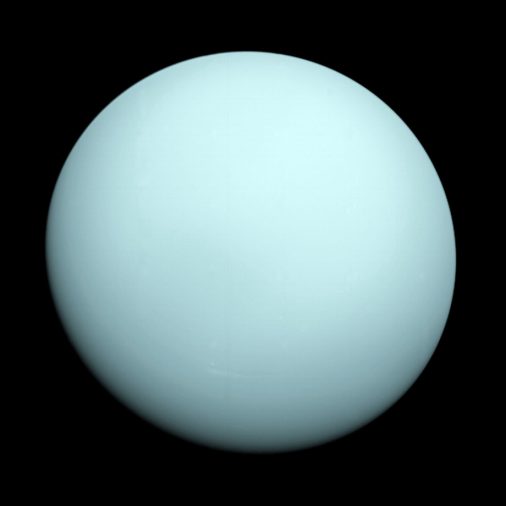

The historic flyby of Uranus took place on January 24, 1986. Voyager 2 passed at an altitude of 81 thousand km from the tops of its clouds. From a visual point of view, the seventh planet looked completely blank. Voyager 2 was unable to detect any characteristic streaks in the atmosphere or major storms on Uranus—only a few bright clouds.

But, as we know, appearances can be deceiving. Although Uranus did not make much of an impression on the outside, what was hidden under its cloud cover presented many surprises.

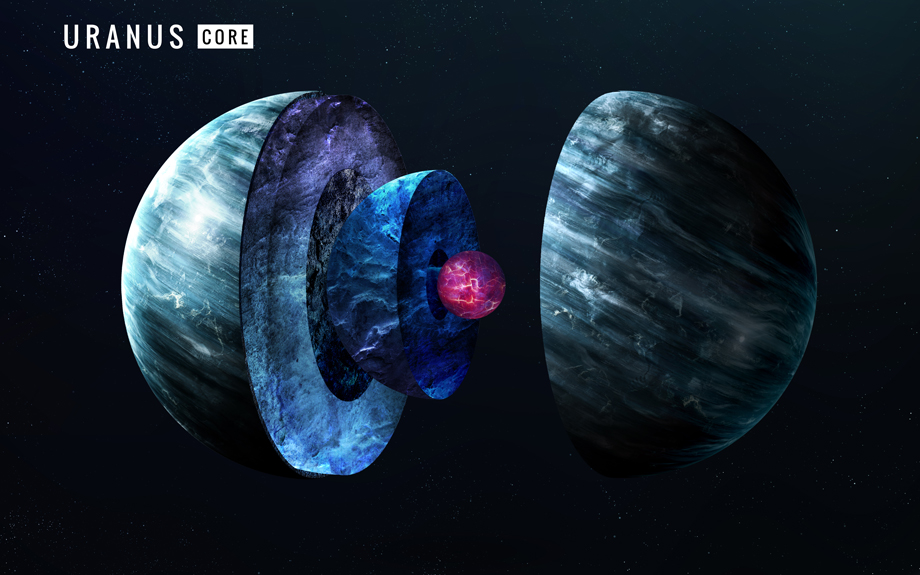

The most important discovery was that Uranus is very different in structure from Jupiter and Saturn. 90% of the mass of these planets is hydrogen and helium. However, on Uranus, only the atmosphere consists of hydrogen and helium. Beneath it is an icy mantle consisting of a mixture of water, ammonia, methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other substances. In the center is a rocky core. Because of these features, astronomers later decided to classify Uranus into a separate subcategory called ice giants.

Another surprise came from Uranus’ magnetic field. Before Voyager 2’s visit, astronomers did not know whether the planet had one, and the probe confirmed its existence. But it turned out that Uranus’s magnetosphere is very unusual and completely different from the that of other planets. The fact is that the magnetic field of Uranus is not directed from the geometric center of the planet, but is shifted from it by about a third of its radius. Because of this, the position of Uranus’s magnetic poles does not coincide at all with its geographical ones. The magnetic field itself is extremely asymmetrical. Its power at the poles differs by an order of magnitude.

Another surprise was that Uranus emits surprisingly little heat. We now know that it is even colder than Neptune, making it the coldest planet in the solar system. The lowest recorded temperature on the planet is -224 degrees Celsius. The main reason for such extreme conditions appears to be the already mentioned long polar nights, when some parts of Uranus do not see sunlight for more than 40 Earth years.

Voyager 2 photographed all of Uranus’s major moons (and also found ten previously unknown ones), as well as its rings. It turned out that the rings consist of a very dark substance, and were presumably formed as a result of the destruction of one of its moons.

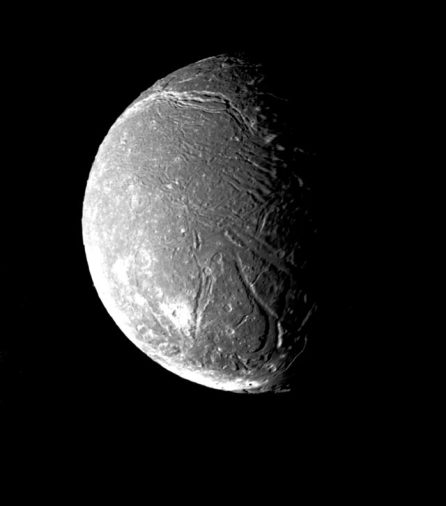

As for Uranus’s moons, Miranda has generated the most interest. Despite its relatively small size, its surface is an amazing mosaic of very diverse zones which contain all sorts of terrains: vast plains dotted with giant canyons, huge faults and cracks, valleys, craters of various shapes, ridges, depressions, rocks, and terraces. One of the main attractions of the satellite is the giant Verona ledge, which is up to 20 kilometers high and is the tallest such structure in the solar system. If you jumped from its top, the flight down will last about 12 minutes. A similar jump was even demonstrated in the famous short film Wanderers.

According to astronomers, Miranda’s rich geology is due to the fact that it was once broken into several parts during a powerful collision, and then “assembled” again in orbit. The collision is also often explained by the anomalous inclination of Uranus’s orbit. Calculations show that this would require a body roughly the size of Earth. The impact itself most likely occurred at the dawn of the solar system, when the planet was under a billion years old.

Future exploration of Uranus

As we have already said, Voyager 2 is currently the only Earth mission to explore Uranus at close range. Since 1986, astronomers have only been able to study the planet remotely – through telescopes or through the New Horizons probe. The latter, although located at a very great distance from Uranus, is capable of observing it from angles inaccessible to earthly observatories.

It is easy to guess that not all scientists are happy with the current state of affairs. Although Voyager 2 enabled a number of interesting discoveries, it provided only a quick look at the Uranus. At the time of the probe’s launch, it was not even known how much Uranus differed from Jupiter and Saturn. Of course, researchers would like to know more about its internal structure, strange weather cycle, and magnetic field. The large moons of Uranus are also of considerable interest, as they may well resemble Europa and Enceladus. It is possible that oceans are hidden under their surfaces, which may hold conditions for the existence of life.

Research on Uranus is also important for astronomers specializing in the study of exoplanets. The fact is that many extrasolar worlds that have already been found are similar in their physical characteristics to the seventh planet. Thus, a new look at Uranus may provide a better understanding of the structure of these worlds.

Given all this, it is not surprising that in the 21st century, a number of projects for new missions have been developed which may be oriented around Uranus. So far, however, they have all remained on paper due to lack of necessary funding.

However, scientists are not giving up. In the 2022, the Decadal Survey of Planetary Sciences (prepared by the National Research Council of the National Academies of Sciences), a mission to Uranus was ranked high on the list of American science priorities for the coming decade.

At the moment, NASA is developing the concept of the Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission, under which an orbiter and an atmospheric probe would be sent to Uranus. The best date for launching this mission is 2031–2032. In this case, it would reach Uranus in 2044. However, these plans may be hampered by both the already-mentioned funding problems and NASA’s shortage of plutonium-238, which will be required to power the device.

China also has a project for a mission to Uranus. It involves a 100-kilogram probe, which is planned to be launched together with the Tianwen-4 apparatus in 2030. It would be set to make a flyby of Uranus in 2036.

Based on all this, it is obvious that those who want to see Uranus again will have to stock up not only on patience, but also with good health to live to see their hopes come true. However, we can only hope that work on a new mission to the coldest planet will be completed. There is no doubt that it still contains many secrets and surprises that are just waiting to be discovered.