Mars has been in the spotlight of both scientists and ordinary people for several centuries. Many see it as a potential second home that could save our civilization from extinction. Others hope to find life there. Others still view the planet as an example of a “failed Earth,” a world that never had a chance to become habitable. In any case, almost everyone has an opinion. Thus, it’s time for us to talk about some of its secrets which humanity has already begun to unveil. The first part of our series will be devoted to the initial period of studying the Red Planet.

The emergence of interest in Mars

Mars has been known to mankind since time immemorial. Its signature red colour, as well as the nature of its movement across the sky, markedly distinguished it from ordinary stars. Astronomers of antiquity left many records of their observations of Mars, and they were able to figure out certain things about the planet. Thus, in the 4th century BCE, Aristotle observed Mars being covered by the Moon, which led him to conclude that Mars had to be much further away from Earth than the Moon.

When the telescope was invented, astronomers discovered that different regions of the planet had different reflectivity. They also figured out Mars’s period of rotation, which turned out to rather closely resemble that of Earth.

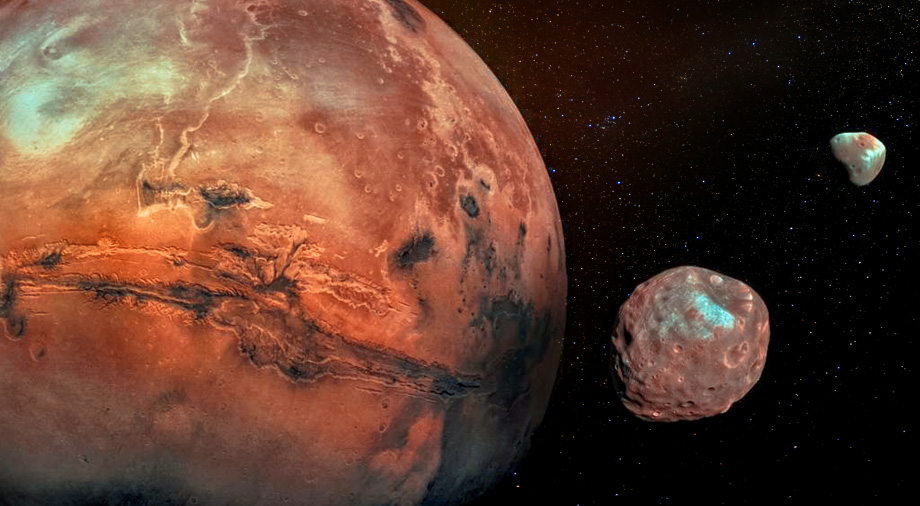

The real surge of interest in Mars occurred in the 19th century. There were several main reasons for this, the first of which was significant progress in the creation of telescopes. More powerful optical instruments have made it possible to detect a number of new features on the Red Planet’s surface and draw up rough maps of it. Astronomers were able to discover that it has two small moons, which were called Phobos and Deimos. Curiously, a whole 150 years prior, Jonathan Swift Jonathan Swift had accidentally predicted the presence of two moons on Mars in his book, Gulliver’s Travels. In addition, the first attempts were made to analyze the Martian atmosphere. They showed (erroneously, as it would later turn out) that it contained a noticeable amount of water vapour.

Another driver of interest in Mars was the popular theory at the time that the further a planet was from the Sun, the older its age, and that the Sun had grown much weaker over time. Based on this logic, Mars would have been older than the Earth and also would have been a much warmer planet in the past. This means that if there were intelligent life on the Red Planet, it would be much older than humanity and thus at a much higher level of development.

All this paved the way for subsequent observations of Martian “canals,” which created a real sensation. Most newspapers of the late 19th century wrote about the existence of these canals and the Martians who built them as a reliably proven fact. As a result, Mars quickly became the star of a new genre that was gaining popularity: science fiction. Authors from all over the world began to write numerous novels which took place on the Red Planet or were somehow connected with it.

It is worth noting that in reality, not all astronomers actually saw these canals. Many rightly pointed out that the maps of them contradicted each other. This meant that the canals were, at best, nothing more than an optical illusion, and at worst, a desire to see something that didn’t actually exist.

However, at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a strong belief in the possibility of intelligent life on Mars. It got to the point that on August 21, 1924, two days before the closest approach of Mars to the Earth in the 20th century, a national day of radio silence was declared in the United States. For a day and a half, all American radio stations stopped their broadcasts for five minutes every hour. At this time, employees of the US Naval Observatory listened to the airwaves to try to catch the signals. The American army even assigned a special cryptographer to decipher messages from the “Martians.” But, of course, his services were never needed.

Photo: nytimes.com

That same year, astronomers were able to measure for the first time the amount of heat emitted by Mars’s surface. The data received indicated huge differences in daily temperatures. This, as well as the results of other observations, dealt a significant blow to the image of Mars as a world favourable for life. It turned out that, in terms of surface conditions, the Red Planet at best resembled Antarctica. Soon the first models of the Martian atmosphere were developed, and while they differed significantly from the real picture, even then it became clear that it was much less supportive of life than that on Earth.

However, all these discoveries only slightly changed the general public’s understanding of Mars as a world where there is, or at least was, life. Even in the early years of the space age, many scientists seriously hoped that at least some primitive vegetation could exist on the Red Planet. Adding fuel to the fire was the hypothesis expressed in 1959 by astronomer Joseph Shklovsky, according to which Phobos is hollow and is in fact a giant orbital station. Later, of course, it became clear that Shklovsky’s calculations were based on erroneous data. But in those years, such speculation only confirmed to the idle public what was already well “known” to everyone. There is definitely life on Mars, and humanity just needed to go find it.

Disappointment of the century

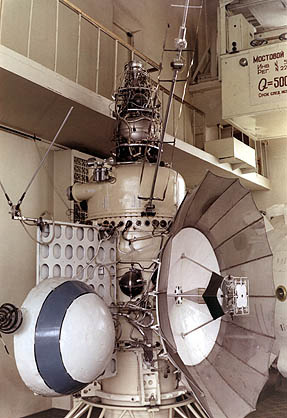

The first attempt to reach Mars was made by the Soviet Union in October 1960. A pair of Object M spacecraft was entrusted with the task of carrying out a flyby of the fourth planet and obtaining photographs of its surface. However, they suffered a fate similar to that of most early interplanetary probes: due to launch vehicle failures, both devices were unable to even reach low-Earth orbit.

Two years later, the USSR tried again. This time, Soviet designers decided to send three devices to Mars at once: two were to explore it from a flyby trajectory, while the third was to make a soft landing on the surface. Looking back, one can only marvel at the courage of the engineers, who intended to take on this challenge nearly blind. It is now obvious that their attempts were extremely ambitious for those years, especially considering the very low reliability of space technology. Moreover, scientists had too little real data about the Martian atmosphere, which made the task of creating an effective landing system almost impossible.

As a result, of the three probes, only one managed to escape from near-Earth orbit and head towards the Red Planet. Due to a leak in its navigation system, this device, called Mars-1, failed midway through the journey.

Photo: NASA

During the 1964 launch window, the USSR planned to send four vehicles to Mars at once and to again try to land on its surface. However, astronomers presented an unpleasant surprise. The latest spectrometric observations showed that the atmospheric pressure on Mars was several times lower than previously thought. This put an end to the idea of a soft landing since due to the overly-thin atmosphere of the already-built descent vehicles, the parachute simply would not have time to open. As a result, three of the four probes were hastily converted for missions to study Venus. In order to deliver a Soviet pennant to its surface, only one, the Zond-2, would be launched towards Mars. However, it never reached his destination due to a breakdown.

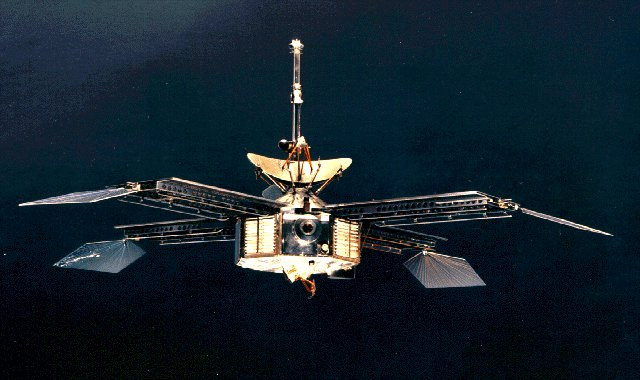

That same year, the United States made its first attempt to reach Mars. The Mariner 3 and Mariner 4 spacecraft were tasked with taking images during a flyby. The launch of Mariner 3 ended in an accident, but Mariner 4 was successfully sent to its destination. On July 14, 1965, the probe passed at a distance of 9,800 km from the Red Planet, transmitting 22 photographs of its surface.

Photo: NASA

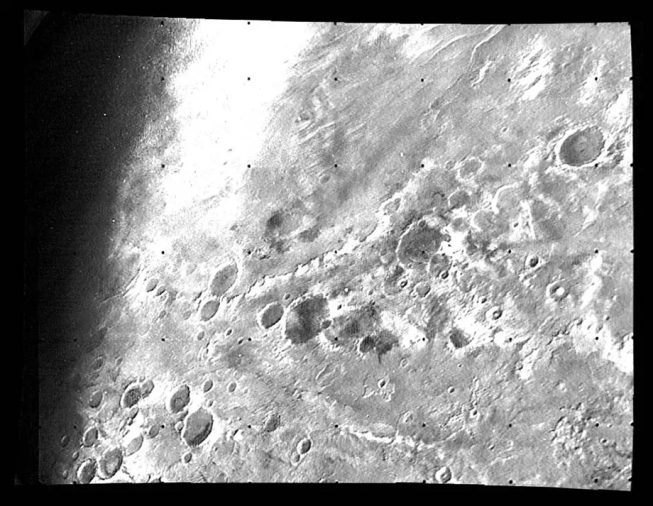

This event was accompanied by enormous excitement. Scientists, journalists, and ordinary people all dreamed of looking at the surface of Mars. Everyone wanted to hear the long-awaited answer to the question whether there was any life there. Employees at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which built the device, were so eager to find out what Mariner 4 had recorded (the photo processing process took quite a lot of time back then) that they simply printed out the data transmitted by the probe in digital form, and then coloured each number in different colours depending on the brightness pixels. This is how the first photograph of Mars from space was born.

Photo: NASA

The data from Mariner 4 left everyone who was hoping to see Mars populated by advanced life bitterly disappointed. Despite the rather low resolution, the photographs captured an ancient, cratered landscape that in many ways resembled the surface of the Moon. Information about the atmosphere of Mars also did not add optimism. It turned out that its density did not exceed 1% of Earth’s, and it consisted of at least 80% carbon dioxide. On top of that, the probe failed to detect signs of the planet having a global magnetic field or water on the surface.

Despite these disappointing results, not all supporters of the theory of life on Mars were ready to accept the end of their hopes. In the end, Mariner 4 only took images of a small part of the planet. But four years later, a new, even more crushing blow was dealt to their dreams. In 1969, four spacecraft were launched to Mars. While the two Soviet probes failed to reach their destination, the American Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 spacecraft made a successful flyby of the planet, mapping approximately 20% of its surface. At the same time, by coincidence, the devices missed the most geologically interesting areas of Mars.

Images from Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 once again showed a very dull, cratered landscape with no visible signs of life. This led to the understanding of the Red Planet as a geologically dead world, where nothing interesting has happened for a long time.

Photo: NASA

The Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 missions coincided with the climax of the lunar race and, in a sense, marked the end of the era of cosmic optimism – the golden era in the history of astronautics when it was believed that humanity would soon conquer neighbouring planets. But these hopes were shattered by exploration missions which showed that the surface of Venus was a hot hell and Mars is a cold and deserted world almost devoid of atmosphere which makes Antarctica look like a resort. Humanity had to come to terms with the idea that it was almost certainly alone in the solar system and say goodbye to dreams of rapid interplanetary expansion. All this contributed to a significant decrease in interest in space research from the general public.

The first globe of Mars

However, despite humanity’s fundamental disappointment in Mars, scientists were not going to be satisfied with what they found. Most of the planet was still a blank spot where the most unexpected discoveries could still lurk. In addition, the question of Mars’s past remained. Was it always a lifeless world, or could the planet have been similar to Earth before?

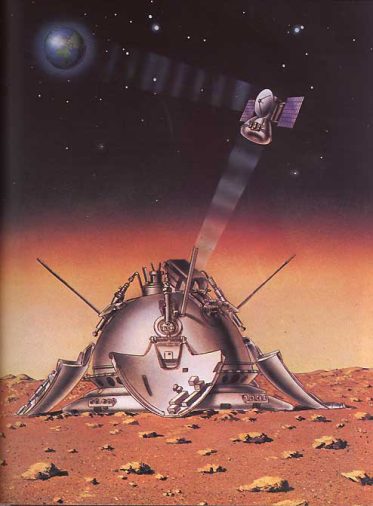

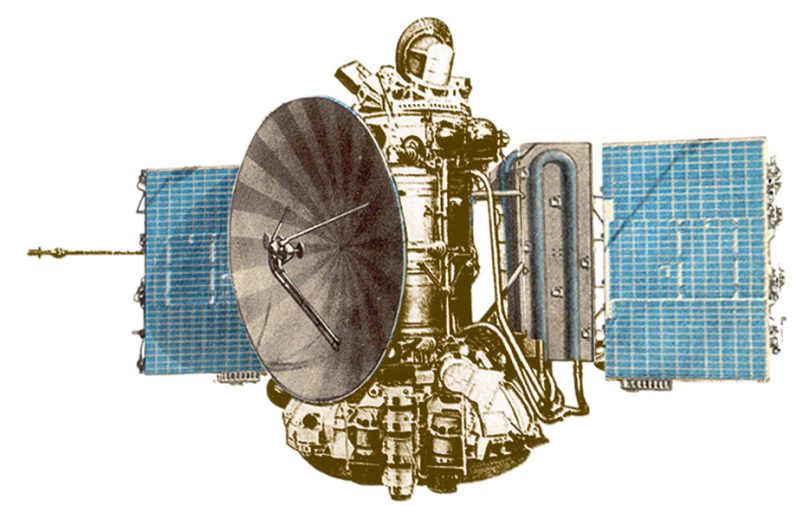

In 1971, a new flotilla of two Soviet and two American spacecraft set off for Mars. The US goal was to place a probe into orbit around the Red Planet and map its entire surface. The USSR again set itself a much more ambitious task, including not just to put a probe in orbit of Mars, but also to send one to the surface with a soft landing.

The American Mariner 8 was the first to leave the race. Due to a malfunction of its upper stage, the device fell into the Atlantic Ocean shortly after launch. Mariner 9 was luckier. In November 1971, it became the first artificial satellite to ever orbit Mars.

Photo: NASA

The Soviet Mars-2 and Mars-3 soon also reached the Red Planet. The Mars 2 lander crashed during landing, while the Mars 3 was a little more successful. Its descent vehicle managed to achieve a soft landing and even began transmitting a panorama of the surface. Alas, this achievement, while outstanding from a technical point of view, did not lead to anything, because just a few seconds after the start of its transmission, Mars-3 fell silent forever. Soviet Mission Control received only a chaotic set of stripes on which nothing could be distinguished. What exactly happened to the device is still unknown. Looking ahead, we can say that Mars-3 marked the high point of the Soviet program for studying the Red Planet. None of the devices subsequently sent by the USSR ever managed to make a soft landing on Mars.

As for the Mars-2 and Mars-3 orbiters, as well as Mariner 9, further trouble awaited them when a planet-wide dust storm broke out on Mars. Mariner 9 had a more flexible program, allowing engineers to delay the start of photography until after the storm had passed. Neither of the Soviet Mars probes could boast of such luxury. On top of all the troubles, the developers of their photo-television installations used the wrong model of the planet and chose the wrong shutter speed settings for the devices’ cameras. As a result, the images they took were overexposed, which, combined with the storm, actually led to the disruption of the main part of the scientific program.

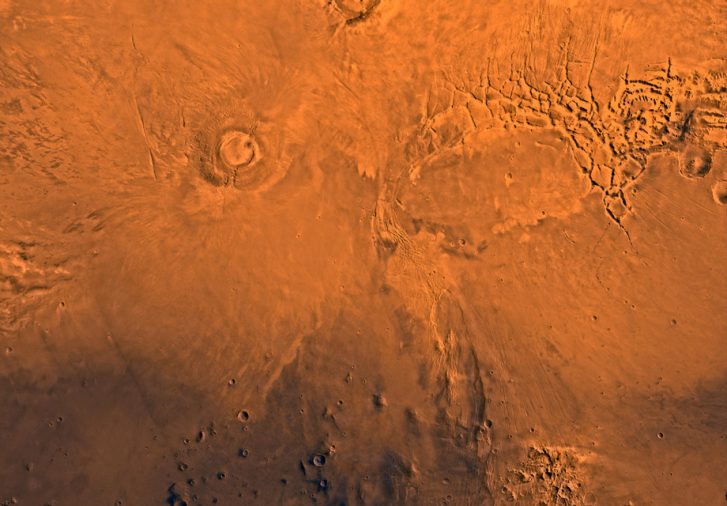

Mariner 9, after the dust settled, managed to map about 85% of Mars’s surface. The probe not only discovered the famous Martian supervolcanoes and a gigantic canyon system (later named Valles Marineris in its honour) but also photographed several formations indicating that streams of water once flowed across the surface of Mars.

Photo: NASA

These discoveries again revived interest in Mars. Yes, the planet is a desert now, but what if life existed on it in the distant past, when it had a full-fledged hydrosphere? To answer this question, new missions were required that could land on the surface of the planet and conduct a detailed analysis of its soil.

An experiment of the century

In 1973, the USSR sent as many as four devices to Mars. Mars-4 and Mars-5 were intended to enter orbit, while Mars-6 and Mars-7 were to land descent modules.

The Soviet bet on quantity did not pay off. Mars 4 failed to reach orbit around the Red Planet and went into space. Mars 5 reached its target but failed after just two weeks. Mars-7 simply missed the planet, passing at a distance of 1,400 km from its surface. As for Mars-6, it entered the atmosphere and transmitted information for 150 seconds, after which contact with it was lost. Modern-day astronomy enthusiasts have been able to identify the crater created by its descent module. However, what exactly caused the accident remains one of the many mysteries of the Red Planet.

It is worth noting that the Soviet Union initially did not intend to stop there. A project for new devices was already being developed, the purpose of which was to deliver Martian soil samples to Earth. But a string of failures that accompanied the Soviet Mars program and the cessation of work on the creation of the super-heavy N1 rocket led to the curtailment of these plans. As a result, the USSR forgot about Mars for a long time.

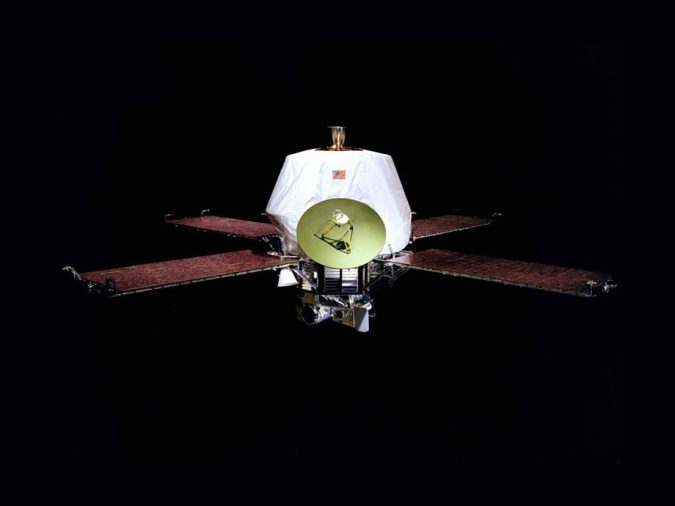

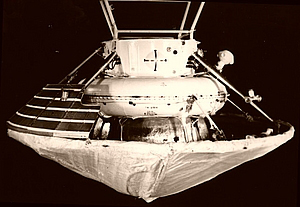

But the United States decided to keep going. In 1975, NASA sent a pair of Viking probes to Mars, consisting of an orbiter and a landing module. Their goal was to completely map the surface of the planet, as well as to study it. The highlight of the program was to be a very ambitious “experiment of the century.” The Viking landers were equipped with biological laboratories which were intended to detect traces of Martian life, should any exist.

Adjusted for inflation, the Viking program cost over $5 billion, making it one of the most expensive interplanetary missions in history. This money was not wasted. The Viking 1 and Viking 2 orbital modules operated until 1980 and 1978, and the landing stations transmitted signals until 1982 and 1980, respectively, which was an outstanding result for those years.

Photo: NASA

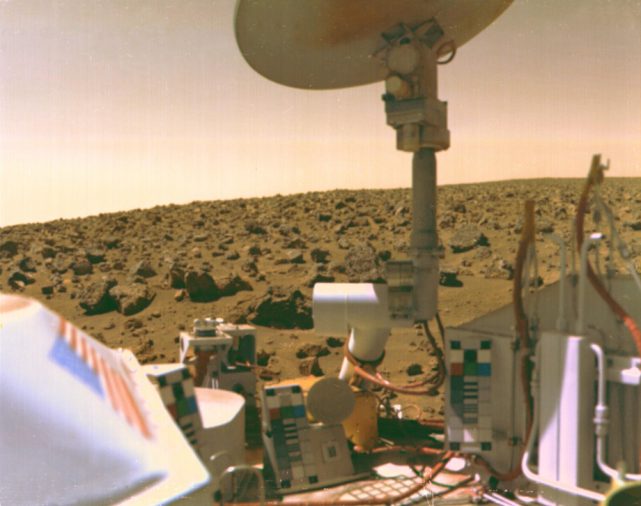

Over the years of its operation, the Viking spacecraft studied the Red Planet in great detail. After looking through the photos they took, planetary scientists found many geological formations that resembled dried-up riverbeds. This confirmed Mariner 9’s findings that Mars was once a much more hospitable world, with streams of water flowing across its surface.

As for the landers, they transmitted the first-ever images from the Martian surface and carried out a detailed analysis of the soil, atmosphere and climate of the planet. However, everyone was primarily interested in the results of the “experiment of the century.” They turned out to be… ambiguous. Soil samples showed unexpected activity, which could be mistaken for signs of microorganism life. However, further analysis showed that the whole point is that the methodology of the experiment itself was not well thought out, and its results could not be interpreted as evidence of life on the planet. Even now, scientists are still debating exactly how to interpret the Viking data.

Photo: NASA

This story became an important lesson for NASA. Yes, the idea of performing one decisive experiment that could provide a definitive answer to the question of the existence of life on Mars sounded very tempting. However, as usual, reality turned out to be much more complicated than they had planned. After this, NASA never again placed such global expectations on its Mars missions, deciding to break the task of searching for life on Mars into a number of intermediate stages.

In any case, although the Viking probes did not find life on Mars, they collected a lot of information that needed to be analyzed and systematized. Fortunately, there was plenty of time for this, because the next launches to the Red Planet had to wait many years.