In early April 2024, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released its new “Commercial Space Integration Strategy.” This document outlined the United States’s strategy for expanding integration with commercial space companies. Attracting private sector space firms to help address national security issues has been of increasing interest to the Pentagon, and numerous military contracts have been concluded with private firms in recent years. With the publication of the new doctrine, however, the Pentagon seeks to promote greater transparency and systematicity within this process.

This article examines which areas of the aerospace industry are of most interest to the American military and, given the risks involved, what kinds of guarantees the DoD must provide to the commercial sector given that the involvement of private businesses in the military sphere increases their risk exposure.

Overview of recent developments

The involvement of the private space sector in security and defense is long overdue. By 2023, when the new DoD strategy was still under development, the United States Air Force (USAF) and the United States Space Force (USSF) had already concluded contracts to procure certain services from commercial satellite operators. In particular, there was interest in using commercial telecommunications satellites to extend the capabilities of military satellite constellations by using them as broadband relays, thus increasing signal resilience and transmission speed.

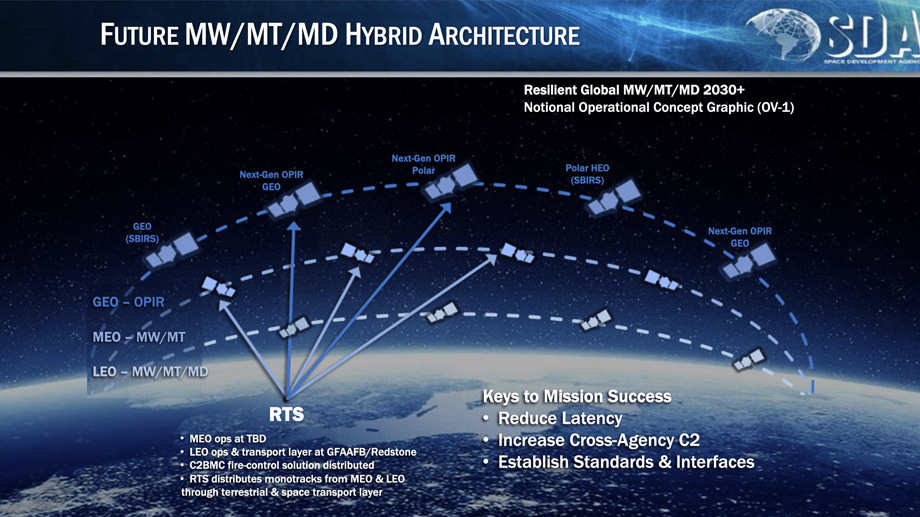

What was envisioned was a unified architecture that would include both commercial and military systems and would involve not only American satellites but also those of allied countries, primarily in the NATO bloc. The creation of this multi-layered satellite network was a frequent topic of discussion during briefings within the United States Intelligence Community (IC), the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), as well as in statements issued by the USAF and USSF.

In practice, these agencies have already been working in one way or another with commercial space companies for years. At different times, this has meant involving private firms in satellite data transmission processes, leasing space technology, or purchasing ready-made services. Such practices have particularly benefited companies engaged in satellite observation and imaging of the Earth’s surface.

It should be noted that, thus far, such initiatives have been purely ad hoc and have lacked a unified, systematic approach in matters of contract procurement, research support, and insurance compensation. Moreover, the internal budgets of organizations like the NRO, the NGA, and other defense agencies have remained opaque regarding how much funding they are willing to allocate for space business integration. As a consequence, commercial space companies have lacked strong incentives to fully participate in defense collaboration.

Credit: Space Development Agency

Some steps in this direction began in 2023, when the NRO awarded contracts to Airbus US, Albedo Space, Hydrosat, Muon Space, and Turion Space, all of which specialize in supplying high-quality electro-optical satellite imagery on demand. These companies joined the Electro-Optical Commercial Layer (EOCL) initiative, which provides U.S. intelligence agencies with satellite observation data from some of the most promising companies in this market. The decision to contract with them became public in December 2023, when it was disclosed during an open NRO briefing.

These firms, however, were not the first to provide services to the NRO: since at least 2022 the agency had also been purchasing data from Maxar, Planet Labs, and BlackSky as part of its first EOCL contracts. Notably, these companies provided crucial intelligence to Ukraine’s leadership during Russia’s invasion in February 2022.

These collaborations followed earlier efforts by the NRO from as early as the summer of 2019, when the organization conducted a series of studies among commercial satellite communication providers to identify the most promising vendors and services. At that time, “training contracts” were awarded to BlackSky Global and Planet, both of which were still in their startup phase.

Pictured: Chuhuiv Air Base on February 24, 2022.

Credit: Planet

Some NRO contracts were also awarded within the framework of the multi-stage Strategic Commercial Enhancement (SCE) program which, in addition to electro-optical reconnaissance, explored the radar reconnaissance, radio interception and countermeasures, and satellite signal relay capabilities offered by modern private space businesses.

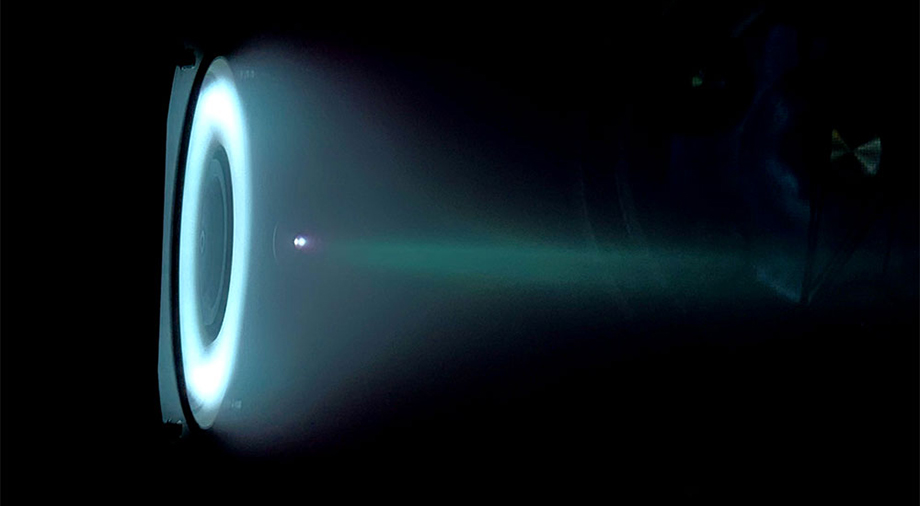

For its part, the USSF has also shown interest in expanding its tactical awareness capabilities using commercial services. The USSF hopes to strengthen the resilience of its networked satellite architecture, known as the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA), the development of which is being overseen by the Space Development Agency (SDA). The primary objective of the PWSA, which is part of the overall Transport Layer architecture, is to consolidate American space reconnaissance capabilities into a single, resilient, and coherent tactical command layer. Geospatial awareness and broadband satellite communications play a critical role in all contemporary conflicts, and it seems that the USSF aims to take the lead in this field.

Credit: BlackSky

However, the PWSA’s tactical-level objectives, which are primarily met by a constellation of satellites operating in low Earth orbit (LEO), are very different from the strategic intelligence goals pursued by the NRO.

According to a recent American Enterprise Institute report titled “Building an Enduring Advantage in the Third Space Age,” the United States has paid insufficient attention to the deployment of satellites in higher orbits. According to the author, Todd Harris, it will be necessary for the NRO to begin focusing on putting large military satellites in geosynchronous equatorial orbit (GEO), a practice the United States successfully employed before the recent LEO boom. Large GEO satellites, Harris argues, will be indispensable in future crises, since Washington’s strategic adversaries already possess the means to quickly disable large LEO satellite constellations, primarily using anti-satellite nuclear missiles. Thus, in the event of a sudden and simultaneous loss of LEO satellite capabilities, individual GEO satellites could still ensure continuous communication with ground-based units anywhere on Earth.

At the same time, a renewed interest in large GEO satellites would also leverage the capabilities of commercial heavy-lift rockets like Blue Origin’s New Glenn and SpaceX’s Starship. Washington’s primary geopolitical adversaries in Beijing and Moscow, meanwhile, lack a reliable means of significantly increasing their military GEO satellite presence.

Harris’s assessment is indeed correct, and the requirement for different levels of satellite support demands more diversified efforts in this area. Consequently, there is a need for increased budgetary resources allocated for these programs. It is currently unclear, however, whether military agencies will be able to sustain such a financial commitment.

Another factor to consider is that the aerospace business models that the Department of Defense is accustomed to working with are primarily geared toward traditional defense industry enterprises. Such models often lack the necessary mechanisms for specific and transparent assessment of the new opportunities becoming available from contemporary space business vendors.

Predictably, this has led to a situation in which the DoD does not always fully recognize the full potential of its investments, making it increasingly difficult for the military to attract new commercial partners. Therefore, it is imperative to organize new, specialized research structures to fill this gap. One model is the Commercial Space Office (COMSO), an internal administrative unit of the USSF that is dedicated to monitoring research in the commercial space sector and facilitating its adoption by the military.

In any case, judging by the steps taken by various military structures within the DoD, the Pentagon has become increasingly interested in expanding its connections with the commercial market over the past five years. The 2024 Commercial Space Integration Strategy thus serves as an announcement to entrepreneurs that “The Department of Defense is finally ready for this, and we have what it takes to make it worth your while.”

What functionality does the military want?

When considering their potential involvement in the military sphere, private vendors must be able to identify the military’s most pressing needs and how they can meet them. The Commercial Space Integration Strategy provides some much-needed answers to these questions.

First and foremost, the document outlines three general categories of operation, which are based on the security permissions granted to commercial companies:

- The realm of primary government missions encompasses mission types that will have minimal involvement from the commercial market. This category includes electronic warfare (EW) systems, positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) systems, missile defense (MB) and nuclear explosion detection (NUDET), as well as military command and control (C2) systems. Understandably, the American government currently has no plans to involve commercial businesses in these areas: information security takes precedence over everything else in such contexts.

- Hybrid missions involve combining the capabilities of military and civilian satellites to enhance satellite communication (SATCOM) systems, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems, EW countermeasures, and space domain awareness (SDA) systems.

- Finally, the domain of commercially oriented missions involves granting commercial companies nearly full control over a spectrum of operations related to space access, mobility, and logistics (SAML). One current example would be SpaceX fulfilling military contracts for payload delivery into orbit. In the future, another significant – and financially lucrative – mission type will be In-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing (ISAM), which will entail satellite servicing, refueling, and related capabilities.

The DoD’s new strategy is a clear signal that the share of contracts with firms operating in the commercial space sector to provide instruments and services will only increase. Ultimately, much will depend on how well the services offered by private firms will meet the Pentagon’s specific strategic goals.

At the same time, another significant factor will be the speed with which a company can deliver its services. In September 2023, for example, Firefly’s Victus Nox mission was able to put a satellite payload into orbit with only 24 hours’ notice, which greatly enhanced the company’s appeal to the DoD and set the bar for rapid delivery.

Credit: Firefly Aerospace

As the Victus Nox example demonstrates, regardless of the systems and services in question, quality and prompt delivery will continue to be a priority. Everyone understands that modern warfare does not wait.

Elsewhere, in the realm of SATCOM, the military’s focus has been on standardizing the different protocols used by satellite telecommunications providers. A situation in which different satellite operators employ different proprietary data protocols significantly complicates the communications landscape, increasing the time required for each transmission-reception cycle. This latency can have crucial repercussions at the tactical level, where every second is critical for determining the outcome of battlefield operations, and minimizing it is therefore a priority.

Standardization of protocols is viewed as the most effective way to address this problem. However, it does carry the risk of exposing private satellite companies’ trade secrets, since competitors will all have access to the same network. To mitigate this problem, it will be necessary for Congress to pass strong regulatory legislation. The military, meanwhile, must be able to provide assurances to commercial players that strict cybersecurity protocols will be implemented.

As mentioned above, another significant capability that the military seeks to have at its disposal is space maintenance and satellite refueling services, which will see significant involvement from the private sector. Although these sorts of forward-thinking initiatives are likely to be implemented on next-generation satellites, support for companies developing such technologies is already in place.

Credit: Orbit Fab

Generally speaking, the military has demonstrated a clear trend toward moving towards a “leasing versus buying” approach when it comes to procuring space equipment. However, in certain domains, including specialized military satellites, this rule has, predictably, not been applied. In 2023, for example, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, traditional military suppliers, were awarded a contract worth $1.55 billion for producing 72 satellites for the Transport Layer satellite network (each company being set to manufacture 36 satellites). In 2024, another contract, this one worth $439.6 million, was concluded between the USSF and Boeing for the construction of a WGS-12 military communication satellite (previous versions of which were also produced by Boeing).

However, such reliance on traditional defense-oriented partners remains largely in the realm of primary government missions, which the Pentagon has no plans to open to commercial players. Elsewhere, including in the space services market, the “lease” approach is likely to prove much more convenient and economically efficient.

Safety incentives and guarantees

Importantly, the Commercial Space Integration Strategy provides relatively clear mechanisms for involving private players in the common cause of protecting national security. The plan identifies four key priorities for the successful integration of commercial space solutions into its military doctrines:

- Commercial solutions, satellite leasing, and service contracts should be applicable across the spectrum of military conflicts (referring to all regions where the US may conduct military campaigns);

- Integrating these solutions before the emergence of a crisis is crucial. In other words, they should be in place before the beginning of a direct military confrontation, when the active implementation of new approaches may be complicated by wartime circumstances;

- It is necessary to establish security protocols for suppliers of commercial space services, as well as financial mechanisms for reimbursing assets in case of their loss due to military actions;

- And, finally, it is important to support the development of new commercial solutions.

While these guidelines are helpful, commercial space firms are still faced with several important questions, not the least of which is just how financially viable this new approach will be. While the Pentagon frequently encourages private sector collaboration, the actual amount of funding allocated for this purpose, as well as the formation of actual budgets and contracts, remains largely opaque.

Indeed, at present there is a certain disconnect between the statements and actions of American military structures in this area. For example, in its 2025 budget request, the USSF did not request any increase in spending for commercial space funding. Meanwhile, the proposed 2024 defense funding law allocates only $40 million in funding for commercial operations related to providing both communications and optical-electronic intelligence services. While such sums may be of interest to new startups, they are plainly insufficient vis-a-vis the aerospace industry as a whole, especially for established companies.

Furthermore, the much higher risks that private civilian companies face in the military sector provide strong disincentives for collaboration without adequate insurance. The space business itself is already quite risky: it is quite difficult to design and build a spacecraft, put it into orbit, and then properly maintain it. So, when that spacecraft also risks becoming a military target, the stakes for commercial firms become even higher.

The U.S. government has some mechanisms in place for compensating risks and potential losses through state commercial insurance. However, at this stage, these protocols only cover maritime and aviation assets. To better reassure space companies, there is a need to develop a legal framework that will specifically cover the space sector. The USSF’s Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve (CASR) program, which is currently in the development stage, represents a positive move in this direction. Similarly, the efforts of commercial entrepreneurs like NewSpace to establish transparent security guarantees and legislative regulations regarding compensation for damages are also important.

Several specific recommendations have been developed during research into the mechanics of cooperation between the military and private business. One RAND report, entitled “Leveraging Commercial Space Services: Opportunities and Risks for the Department of the Air Force,” made several concrete recommendations for hastening the integration of private enterprise into military affairs:

- Actively analyze opportunities in the commercial space services market and explore the viability of new technologies at the earliest stages of their emergence;

- To increase the complexity of contracting, make contract requirements more specific and precise;

- Adopt a flexible approach in providing companies with necessary resources, especially in negotiations regarding service contracts. This can significantly expedite their execution;

- Engage in limited investment strategies in the early stages of developing space services (such as the prototyping phase, etc.), when market risks and investment returns are still uncertain;

- Attract companies offering services with relatively low market risks, or develop a mechanism for distributing these risks among as many stakeholders as possible.

While these are all good recommendations, the truth is that the current situation is one in which words on paper substantially precede meaningful action. Until entrepreneurs begin to see concrete initiatives implemented with adequate budgetary support, progress in this field is unlikely to advance very far.

Recent years, however, have demonstrated that making important strategic decisions (be it military support for allies on the ground or crucial decisions about space policy) can be very difficult for policymakers in the United States. Nevertheless, with the advent of the Commercial Space Integration Strategy, this process has at least commenced. Now, it is just a matter of waiting until the system is ready.