The aerospace transport sector, which can be conventionally divided into launch vehicles (for launch) and spacecraft (for travel in space or atmosphere), promises plenty of interest to come this year. Some aerospace concepts will stem from approaches and developments from previous years (and even decades), while others will be debuting for the first time.

Let’s take a look at the main presentations of the rocket and space industry, scheduled for 2024, and try to understand what requests they form for the modern aerospace industry in general.

Heavy and reusable: vision of the ideal launch vehicle

A kind of “interlude” to the replenishment of the rocket variety was performed by Blue Origin, having carried out a successful mission with the landing of the first stage of its New Shepard rocket. Despite the fact that the launch took place as early as December 19, 2023, it points to a continuing demand in the sector for return-capable rockets. This is particularly the case with launch vehicles from super powerful propulsion systems or spaceships with a set of advanced electronics, because the loss of these modules greatly reduces earnings from the launch.

Pictured: Landing the first stage during the NS-24 mission

Jeff Bezos’ company Blue Origin is of course not the only giant in the rocket market that is betting on return modules, as SpaceX has been doing so since 2016. However, while SpaceX uses its Falcon 9 to launch payloads into Earth orbit, Blue Origin classifies its New Shepard as a suborbital rocket for space tourism purposes. For cargo launches, Blue Origin has the New Glenn, which is also re-usable, and is set to debut this year. The rocket will be able to send up to 45 tons into low Earth orbit, and up to 13 tons into geostationary orbit.

Blue Origin took a long 15-month pause after its failed most recent attempt to launch New Shepard in 2022. This embarrassing fiasco was preceded by 22 consecutive successes. The company has already stated that during 2024, it will increase its launches of its new rocket for commercial orders, as Blue Origin is already getting higher demand for these services.

SpaceX is also making moves in 2024. This year, we should see new Starship/Superheavy launches, with which SpaceX plans to deploy a presence on the Moon as part of NASA’s Artemis lunar program. Two launches took place last year in April and November, but were only partially successful, as both launches ended in the loss of the rocket and spacecraft. These rockets were billed by SpaceX as fully reusable (both the booster and the spacecraft), so in 2024 the company intends to rehabilitate its image with a third Starship/Superheavy space launch.

It should be noted that the upcoming Starship/Superheavy launches are only a small part of SpaceX’s global plan to deliver large volumes of cargo to the Moon. In order to achieve the announced goal for which Starship/Superheavy was designed — the delivery of 100 tons (with a possible expansion to 150 tons) of payload to the Moon, Elon Musk’s company plans to refuel its rockets in orbit. Currently, during future Artemis missions, a single rocket launch to the Moon will require three more boosters. Thus, the first will deliver the Starship/Superheavy modification into orbit, which will act as a refueling station, while the next two launches will fill it with metalox fuel via docking in orbit. A possible fourth Starship/Superheavy rocket will carry people or a payload on board and, after refueling from the orbital refueling module, will be able to head to the Moon. This plan of actions will allow SpaceX to deliver large volumes of cargo during future colonization missions.

The scheme proposed by Musk is effective, but too complex, because it requires a serious burden on SpaceX’s manufacturing capacity. Current plans to achieve all the goals of the Artemis program, according to preliminary calculations, will require at least 20 launches of SpaceX’s Superheavy rockets. And if they were all headed to the Moon, 75% of these launches would be needed to prepare just one translunar trip.

Solving the in-orbit refueling problem (or at least reducing the number of rockets that will be used during this part of the mission) may be an essential challenge for SpaceX. The reduction in NASA budgets observed throughout 2023 demonstrated that the space agency is not ready to overpay even for the implementation of its most ambitious projects. This was the case with the Mars Sample Return (MSR) program, which is now suffering from a totally devastating lack of funds. Today, launching one Starship/Superheavy costs approximately $100 million, with a $400 million price tag for a trip to the Moon, but Elon Musk believes that in a few years it will be possible to reduce this amount to $10 million. If SpaceX manages in the coming years to get many commercial orders and increase its number of rockets, things might work out as they have with the Falcon 9 and Heavy.

While SpaceX is making plans for future trips to the moon, China’s combined industrial might is trying to keep up with it in regards to launching orbital Earth rockets. China’s oxy-fuel Tianlong-3, produced by the commercial company Space Pioneer, plans to debut in 2024. The rocket is very similar in design to SpaceX’s Falcon-9, which is exactly how it is positioned in the Chinese press.

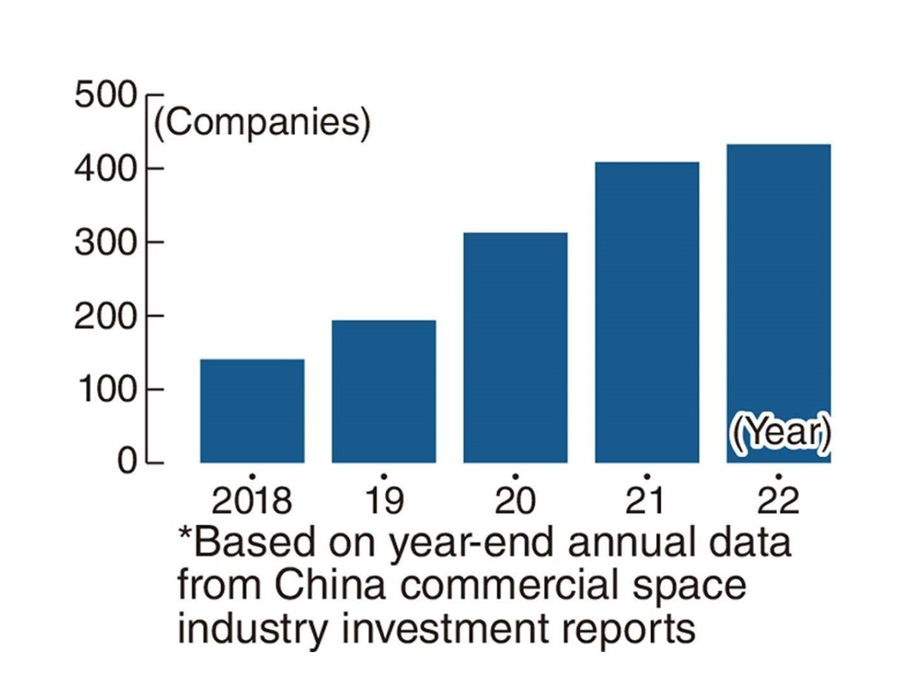

However, even now it is noticeable that, at least in terms of carrying capacity, Tianlong-3 will be inferior to its American competitor. The rocket from Space Pioneer will be able to lift only 14 tons of payload into low Earth orbit (LEO), which is more than a third less than the Falcon-9 already offers to the user. In addition, it is obvious that the Chinese private rocket sector still makes up a significantly smaller share of the total rocket sector of the PRC, and accordingly has a much smaller industrial capacity. It should be noted here that the share of commercial space companies in the PRC is steadily growing, but they will definitely not become fully competitive with the US private aerospace market in 2024.

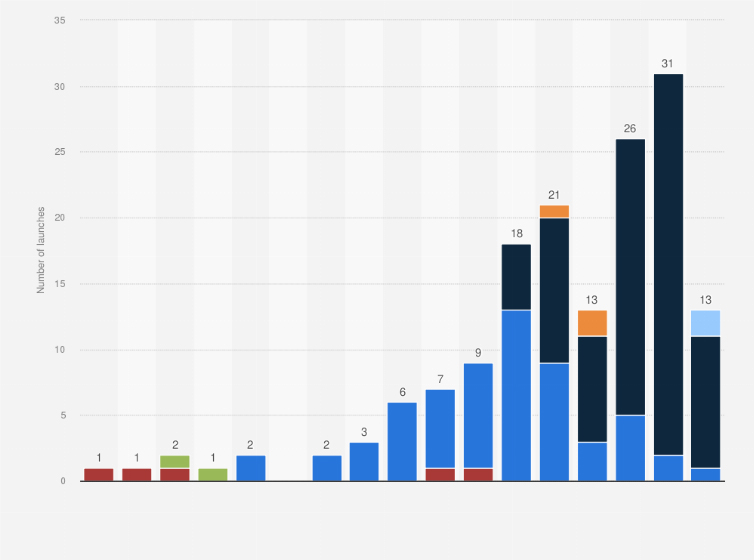

This is what prompts us to doubt the ability of Chinese aerospace companies to even come close to the number of launches currently offered by American space companies. And although SpaceX did not reach 100 launches of its Falcon-9 in 2023, according to the company’s latest statements, it intends to achieve 12 launches per month in 2024, meaning an annual plan for an incredible 144 launches. To understand the scale of these ambitions, let’s note that in 2023, the whole world carried out 210 successful orbital launches (108 of which belonged to the US).

It is not only the giants of the aerospace industry which are hoping to increase their rocket production. The American aerospace company Firefly Aerospace has plans to increase the production of its small Alpha class launch vehicle to 24 per year. Although Alpha does not have a return stage, it offers customers a low-cost solution built specially for delivering small loads to LEO. However, the production of 24 rockets per year is unlikely to be achieved in the next 12 months. There are currently 10 planned future Firefly Alpha missions, of which four are planned for 2024, with another six expected in 2025.

As for the Chinese national rocket manufacturing industry, 2024 is expected to see the debut of a new version of the Long March 6C (CZ-6C) rocket, similar to the first stage of the Long March 6, but with two rocket engines. The approximate cost of delivery per 1 kg of cargo into orbit using the Long March 6C starts from ¥87 000 (≈ $611). Of course, China continues to surprise with its prices, but it is moving quite gradually and is not in a hurry to achieve big results here and now.

The European Space Agency (ESA) will also most likely receive a new rocket this year. The next generation Ariane 6 is already in the final stage of testing on Earth and is due to make its first demonstration flight this year. The upper stage of the new European rocket will also be reusable, which opens up wide opportunities for launching European scientific missions within the solar system, with the subsequent return of extracted samples to Earth. So far, the debut of Ariane 6 is scheduled for June or July, and more detailed information about the mission will be released six weeks before launch.

The Ariane 6 is not the only rocket Europe is waiting for. The first flight of the Vega C medium rocket in a year and a half could take place as early as autumn. It is on this rocket that ESA plans to carry out the missions of its new reusable unmanned spacecraft Space Rider, which is being developed for scientific research in outer space and the Earth’s atmosphere.

Space Rider will land like an airplane using special modernized runways customized for spaceships designed for long-term journeys in orbit.

Space agencies are focusing on increasing the duration of crewed trips.

Manned and cargo spacecraft

ESA’s pace Rider will be the long-awaited, but far from the only spacecraft that will launch in 2024.

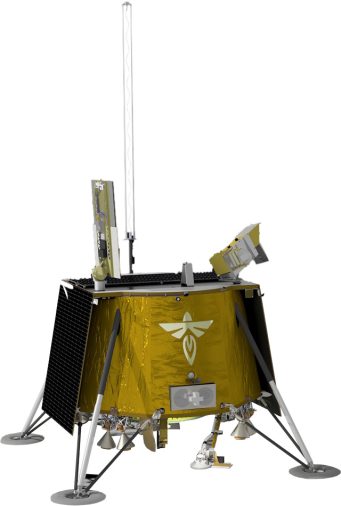

This year, Firefly Aerospace will send its Blue Ghost lander to the Moon, with the launch taking place between the 3rd and 4th quarters of 2024. Last March, Firefly received a $112 million contract from NASA for the delivery of a second Blue Ghost landing platform to the far side of the Moon in 2026.

NASA’s agreement with Firefly is the eighth contract under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. In 2024, Intuitive Machines will also fulfill its own order. The company will carry out three consecutive missions using the Nova-C robotic landing platform, which will deliver a NASA payload to the surface of the moon.

In the sector of space transporters, there is an obvious growing demand for long-duration crewed flights. Today’s spacecraft demonstrate phenomenal capability for long-duration suborbital journeys, guaranteeing advanced levels of safety, navigation, communications, and control. In addition, the number of astronauts who have to go on long journeys every year is increasing again. Twenty six astronauts in seven missions will launch from the Kennedy Space Center (Space Force station at Cape Canaveral) alone in 2024. This is the largest number of launches in the last 15 years, trailing behind only 2009, when towards the end of the Shuttle program, Space Center launched 35 American astronauts. However, while all astronauts in 2009 came from government institutions, in 2024, only 14 of the 26 astronauts launched will belong to NASA and partner country space agencies, while the 12 remaining slots will be available to others as a private service. It is possible that the number of commercial astronauts may exceed the number of government ones in 2024. This change is an expected result of the strengthening position of private companies that offer such solutions.

Even those space tourism companies which suffered a stunning collapse last year will try to get back on their feet. Thus, the company Virgin Galactic was forced to admit the failure of its strategy for organizing suborbital flights with its ship, VSS Unity. This spacecraft could make only one trip per month, so only six crew members could reach Earth’s orbit. This sparse flight schedule led to significant losses, since the preparation of the flight cost significantly more than the four tickets sold to board it (two seats were reserved for the spacecraft’s pilots). In the end, Virgin Galactic resorted to radical solutions, laying off 18% of its staff and completely suspending ticketing and flights of its VSS Unity to focus on developing a new modification of its Delta spacecraft.

According to the scraps of information known at this point, Delta will increase the number of seats on board to eight (along with two pilots) and conduct up to one launch per week. 2024 will tell us whether Virgin Galactic will have time to prepare its Delta for launch this year. The company plans to put into operation its new spaceship manufacturing plant in 2024.

The urgent replacement of VSS Unity by Delta clearly demonstrates the key conditions necessary for the success of the space tourism business as such – a high density of launches and more spots on board. However, price remains an obstacle to obtaining a significant number of orders for a suborbital flight, with the price of a single passenger seat on the already-used VSS Unity costing $450,000.

The space transporter sector predictably seeks to increase the carrying capacity of its new models. The PRC is doing this better than anyone else so far. At the beginning of 2024, the Tianzhou 7 cargo ship will be launched on board a Chinese Long March 7 rocket, which can deliver 14 tons of payload into orbit. China is showing impressive progress in the development of heavy-duty orbital carriers. For comparison, the American Crew Dragon from SpaceX is capable of delivering only 3,300 kg of payload to the ISS.

The emergence of new heavyweights like the Tianzhou is becoming vital to creating a sustainable logistics chain that can supply the recently built Chinese Tiangong Orbital Station, conducting timely crew rotations and meeting the astronauts’ needs for food and air. China plans to launch another Tianzhou 8 cargo mission sometime in late 2024. Both missions will deliver two crew rotations to Tiangong — Shenzhou 18 and Shenzhou 19, China’s primary manned spacecraft.

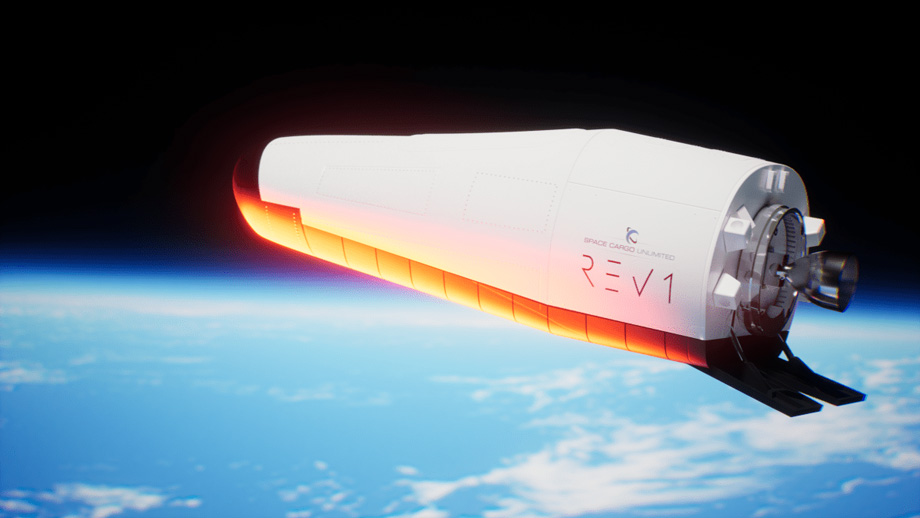

It is reusable unmanned spacecraft that are expected to become the future of the orbital manufacturing industry. This view is held today by a number of companies, including Thales Alenia Space, which aims to introduce its REV1 cargo spacecraft without a crew by 2025. The ship will be able to lift up to one ton of payload into orbit, with the possibility of a long-duration flight (Thales Alenia Space itself speculates that REV1 will be able to orbit for several months and dock with orbital service modules, which the company is also developing). The ship could become indispensable for the expansion of the market of space biotechnologies and pharmaceuticals, as well as among companies seeking to create products from space resources.

The greater convenience of using unmanned carriers compared to manned spacecraft lies in the greatly simplified safety system and the absence of the need for morally complex decisions. While manned ships must prioritize the safety of their crews over that of their payloads in emergency situations, unmanned ones will simply not have this choice. Of course, there will always be the risk of automation failure and the failure of critical spacecraft systems (which could be fixed by a human on board), but it is incomparably less serious than a situation in which an expensive payload will be lost by default in order to save human lives. In addition, unmanned missions, which do not require expenditures on crew training, are far more useful in organizing space missions for the production and delivery of supplies.

We will see what progress REV1 makes this year, but we are unlikely to see the spacecraft launch until 2025. As for manned space missions, they will have more advantages in the organization of future planetary missions (the Moon and Mars are already twinkling on the horizon), as they will require the physical presence of specialists at future extraplanetary bases. Reliable, stable manned spaceships and orbital carriers will become an indispensable link in organizing long-term human habitation on other celestial bodies.