Unlike many countries and private companies, China did not launch any new missions to the Moon in 2023. The Celestial Empire compensated for this by intensifying plans to create its own lunar coalition, acting as a sort of counterweight to the Artemis Accords coalition. The Beijing-centered bloc included countries such as Azerbaijan, Pakistan and South Africa.

But what are China’s successes in this field? And how does the new lunar race differ from the previous one? Let’s look closer.

A Brief History of the Chinese Lunar Program

Chinese leadership began developing a national lunar program back in the 1990s. Its existence was officially announced in 2004. It was named Chang’e, in honour of the Chinese goddess of the Moon. The program was divided into four main phases.

- The first phase was to send orbiters to the Moon capable of making detailed maps of its surface in order to select suitable landing sites for future missions.

- The second phase involved landing stationary platforms with scientific instruments and autonomous rovers on the lunar surface.

- The third phase would be marked by taking a sample of lunar material and bringing it back to Earth for study.

- The finale of the Chang’e program was to be the construction of a robotic research station at the Moon’s south pole, which would lay the foundation for the subsequent construction of a habitable base.

After outlining its goals, China began to methodically implement its plan. The first launch to the Moon took place in 2007, when the Chang’e-1 station successfully entered a selenocentric orbit and compiled a detailed map of the lunar surface, as well as assessing the distribution of a number of chemical elements in the lunar crust.

Photo: china-pictorial.com.cn

Three years later, China sent its Chang’e-2 to the Moon. It had the same design as its predecessor, but with a more advanced camera. Chang’e-2’s main task was to find a suitable landing site for China’s next lunar mission.

Chang’e 2 successfully completed its task, paving the way for the third probe, which was intended to carry out a soft landing on the Moon. To understand the complexity of this challenge, it is important to remember that no one had ever successfully carried out a soft lunar landing on the first attempt. China, however, did, completing a safe landing on the Moon on December 14, 2013, Chang’e-3 became the first earthly emissary to the Moon since 1976.

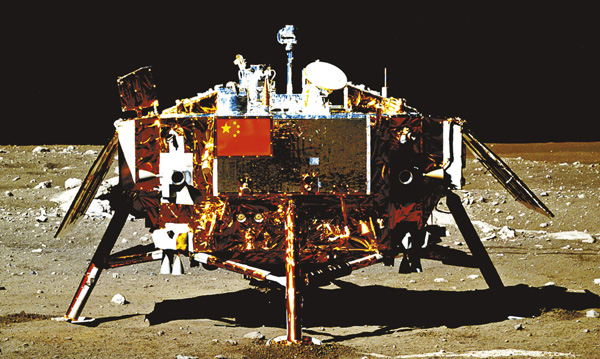

Photo: xinhuanet.com

The Chang’e-3 delivered to the lunar surface not only a platform with scientific instruments, but also the 140-kilogram Yutu – the first wheeled vehicle on the Earth’s satellite since the time of Lunokhod-2. The nominal lifespan of the lander was one year, and that of the rover was three months. However, the Chinese lunar rover managed to keep operating for 31 months, and radio enthusiasts still manage to periodically pick up the lander’s signals to this day, indicating that it remains functional now.

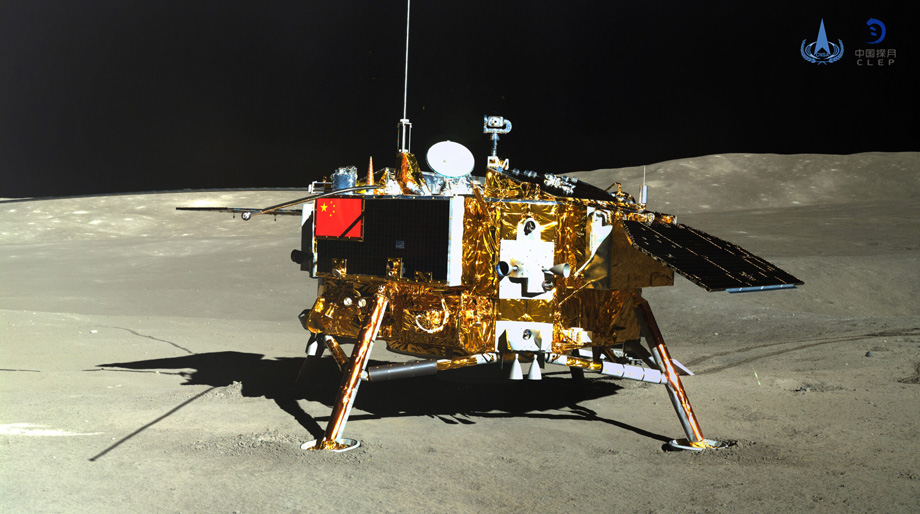

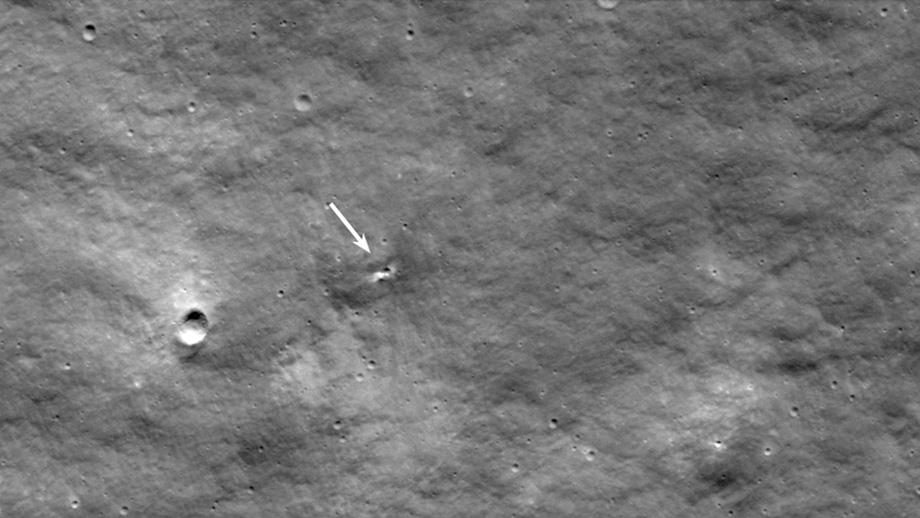

Photo: doi.org

The next Chinese mission, Chang’e-4, was even more ambitious. The Celestial Empire decided to land a lunar rover on the far side of the Moon. To do this, China first sent a special relay satellite, Queqiao, to the L2 Lagrange point of the Earth-Moon system. It was followed by Chang’e 4 itself. The probe launched on December 7, 2018, and a month later made a historic landing in the southern part of the Karman crater on the far side of the Moon. The success of this mission marked China’s transition from the phase of merely replicating old Soviet and American achievements to the phase of conquering new milestones.

But Chang’e-4 earned a spot in the history books not only because of its landing site. In addition to traditional scientific equipment, the device carried a sealed container with a closed life support system containing seeds and insect eggs. A few days after planting, a camera installed inside the cylinder recorded the germination of one of the cotton seeds. This is the first time in history that an earthly plant has sprouted on another celestial body.

Photo: Beijing Control Center

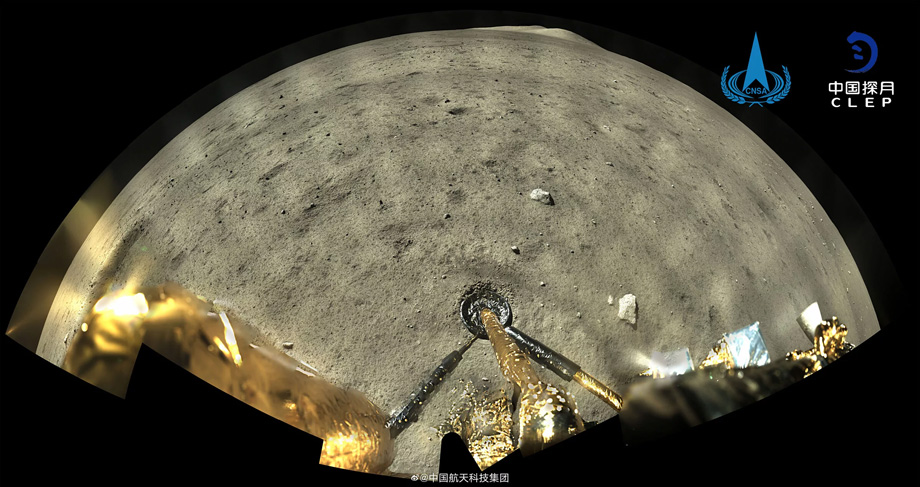

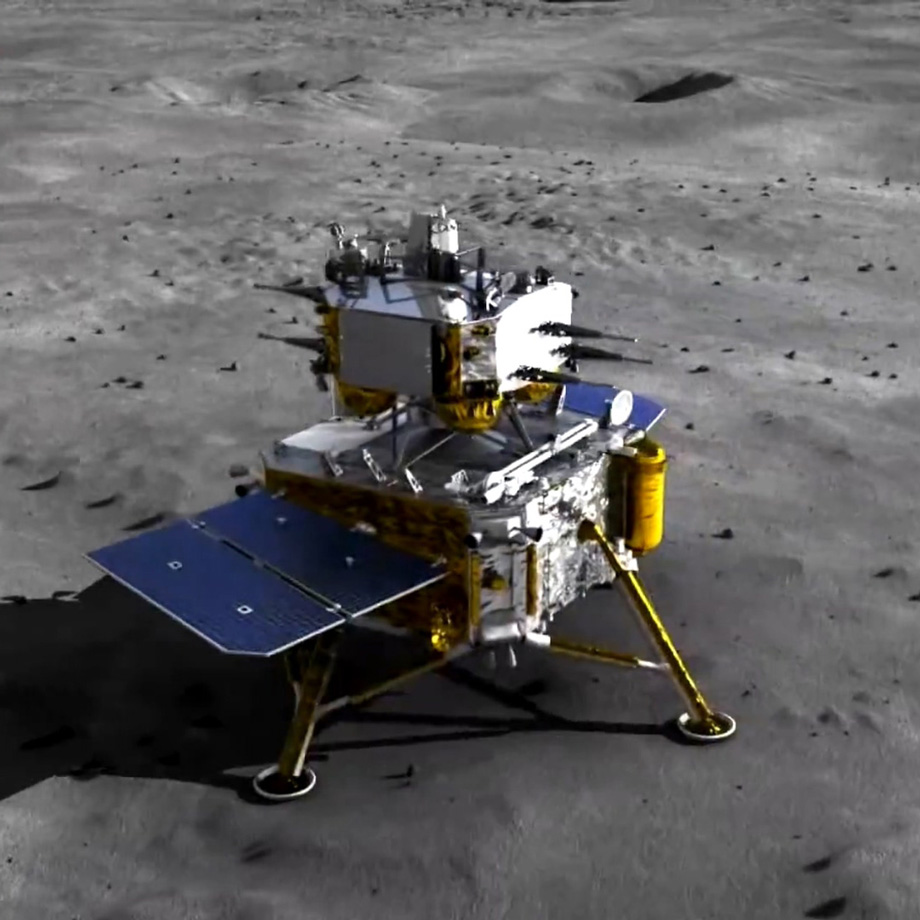

The most recent Chinese lunar mission was Chang’e-5, whose purpose was to deliver a sample of lunar soil to Earth. Preparations for it began back in 2014, when China launched the Chang’e-5T1 probe. It circled the Moon, then headed back towards Earth and deployed a test capsule. This was a dry run for the main stages of the future Chang’e-5 mission.

Chang’e 5 launched towards the Moon in November 2020, and went off without any difficulties.The lander successfully landed in the area of Rümkera Peak (a volcanic formation in the northwestern part of the visible side of the Moon) and took a soil sample. The sample was then transferred to the return module, which set off on a return course to Earth. The sample capsule landed in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region on December 16, 2020.

Photo: CNSA

Subsequent analysis showed that the samples delivered by Chang’e-5 were formed up to 2 billion years ago. That is, China received at its disposal much “younger” soil samples than those delivered to Earth by the Apollo expeditions and the Soviet Luna stations.

Immediate plans for the Chinese lunar program

The implementation of the Chang’e-5 mission drew a line under the third phase of the Chinese lunar program. The country’s scientists and engineers are now working on its next stage.

As early as March 2024, China plans to send a new relay device to the Moon to support the Chang’e-6 mission, which is scheduled to launch in May. It will land on the moon’s south pole and then return a sample of soil to Earth. The choice of this region is not at all accidental. It is the south pole that is considered one of the most suitable places for establishing the first human lunar settlement.

Photo: China News Service

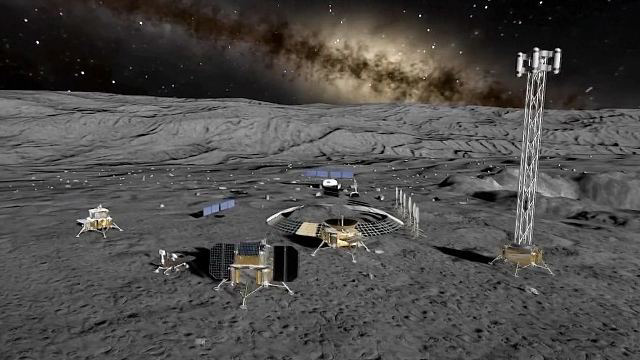

Following Chang’e-6, China will send two more unmanned spacecraft to the Moon: the Chang’e-7 and Chang’e-8. Their main goal will be a comprehensive study of the South Pole. These missions will include landers, rovers, and even aircraft. In addition, the missions will test certain technologies that may be useful to China’s taikonauts during their construction of a future base. One example is 3D printing using regolith as a raw material.

Photo: CFP

The next step will be to land taikonauts on the moon and build a permanent base there. China has not kept these plans secret. In 2021, the PRC signed a memorandum of cooperation with Russia regarding the creation of the so-called International Scientific Lunar Station. At that time, it was assumed that the Luna 25, Luna 26, and Luna 27 missions would serve as Russia’s contribution to the project.

However, Russia then launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. After this, many observers noticed that China stopped advertising the aggressor country’s participation in the project at international forums. And the inglorious death of Luna-25 finally made it clear that the Russian Federation is unlikely to be of much help to China in the exploration of the Moon, and may even be detrimental.

Photo: NASA

Be that as it may, Chinese engineers are already hard at work creating technology for a manned lunar program. Thus, in 2020, they carried out a successful test of a prototype of a new generation spacecraft designed both for delivering taikonauts to an orbital station and for missions into deep space. It was launched into low-Earth orbit and performed a series of maneuvers that made it possible to increase its apogee to 8000 km. Thanks to this, the ship’s capsule entered the earth’s atmosphere at a speed of about 9 km/s, which is higher than during conventional flights to low Earth orbits. This made it possible to test thermal protection under conditions reminiscent of returning to Earth from an interplanetary expedition.

However, when it comes to a mission which involves the landing of taikonauts, then just one ship will not be enough. For this, China will also need a separate lander and a fairly powerful rocket capable of delivering it to the Moon.

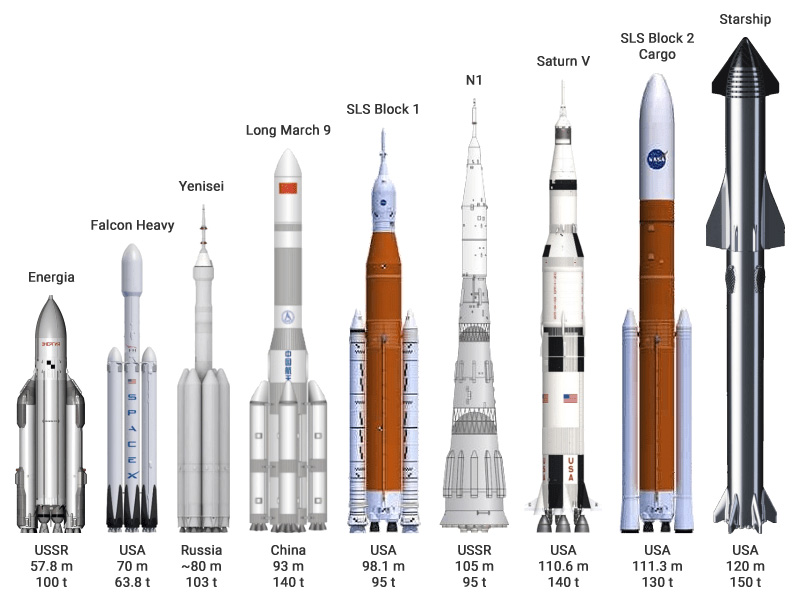

Currently, China is busy creating two such carriers at the same time. The less powerful short-range rocket is called the Long March 10. It will be able to launch up to 27 tons of cargo on a flight path to the Moon, which is comparable to the carrying capacity of the American SLS in its basic configuration.

The current plan is to use two Long March 10s for the lunar mission. One will send a ship with a crew to the Moon, while the second will send a lunar lander. They will dock in a selenocentric orbit, after which the taikonauts will descend to the moon, land, and hoist the red flag. At the moment, China plans to achieve this goal by 2030.

It is important to understand that the expedition described above will last several days and will essentially represent a repeat of the Apollo missions. In order to set up a permanent base at the south pole of the Moon, the PRC will need a much more powerful carrier. This will be the Long March 9 rocket, which has been in development since the mid-2010s. In addition to missions to the Moon, the Long March 9 is expected to be used for assembling various space structures, as well as flights into deep space.

Image: ixbt.com

However, the Long March 9 carries an element of uncertainty with it. After the Chinese government approved plans for the rocket, its design was radically altered several times. It started as a classic super-heavy rocket with a large number of disposable stages and boosters. The project was then revised, and the carrier received a reusable first stage. Further, apparently with inspiration from SpaceX’s Starship, the designers proposed creating a fully reusable two-stage rocket. Then they returned to the idea of a three-stage rocket with a reusable first stage. It is possible that in the future, Long March 9 will again go through some kind of metamorphosis.

In any case, Chinese leadership expects that the Long March 9 will be put into operation at the beginning of the next decade. This will allow the construction of the International Lunar Station by 2035.

It is still difficult to predict who will get to the Moon first. In theory, the United States has a few years of head start, but in practice everything will depend on the speed at which Starship is commissioned. It is now obvious that the rocket will clearly not be ready to fly to the Moon by 2025, as was set forth in the current plan. An estimate of 2027-2028 looks much more realistic. But if the construction of Starship continues to drag on, this will give China a good chance to make the first manned.landing on the moon in the 21st century.

It should be understood that despite the great propaganda effect of this event, the event in itself will not affect the outcome of the second lunar race. The main thing will be how successfully the parties are able to solve the problem of delivering a large amount of cargo to the Moon and building a permanent base there.