The world is hearing more and more news about North Korea, ironically named the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), in the context of new missile launches, the deployment of spy satellites, and even the country’s supply of ballistic missiles to aid Russian aggression against Ukraine. This is not the first decade in which the small “aquarium of communism,” tightly preserved since 1953, has threatened the world in all directions with its missiles. But if earlier such intimidation was a figment of North Korean propaganda’s imagination, today the threat is not so far from reality. The missile sector of the Juche country is constantly expanding, bypassing the sanctions imposed by the UN with the direct participation of its closest neighbors: the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation.

North Korea’s accumulation of missile weapons and the development of its own nuclear program clearly indicate that the country remembers the main idea of its founding – the spread of Juche communist ideology throughout the Korean peninsula. At first, Pyongyang pursued this goal mostly alone, but it has recently brought in influential allies whose missile capabilities promise to make this absurd dream a reality.

The first part of our material will be devoted to the formation of the DPRK’s missile arsenal in the 20th century.

The start of support: Soviet jets of the Korean War era

The first Soviet jet technologies reached North Korea during the Korean War of 1950-1953, but they did not yet include ballistic missiles. The newest Soviet MiG-15 jet fighters began their first combat sorties in November 1950, just as the war between the two Koreas had become an ideal testing ground. The planes had North Korean and Chinese markings, and at the beginning of the war, the jets were mainly flown by Soviet pilots. American pilots repeatedly heard Russian in the whirlwind of air battles.

In some ways, the MiG-15 surpassed its main competitor, the American F-86 Saber jet fighter, which fought on the side of South Korea. The Soviet aircraft had a higher altitude ceiling and a higher rate of climb (9,200 feet per minute, as opposed to the Sabre’s 7,200 feet). In case of danger, Soviet MiGs were able to skilfully withdraw from the battle, rising to a height unreachable for American fighters.

The jets also carried superior armaments to their American prey. The MiG-15’s H-37D automatic 37 mm cannon was capable of hitting targets at a range of 1 km, which was considerably further than the range of the weapons carried by American aircraft. For example, the machine guns installed on the protective turrets of American B-29 bombers could only be aimed at up to 400 m, meaning the Soviet MiGs had a 600-meter window for aimed fire at speed without risking being hit by the bomber’s fire. American bombers simply could not carry out their missions without fighter cover, as was the case during World War II.

However, the advantages of the MiGs quickly evaporated in the hands of North Korean pilots. Their lack of experience and deficient understanding of even the basics of air combat was immediately noticeable to the American pilots in their F-86 Sabers.

Source: National Museum of the United States Air Force

However, the DPRK had no chance of winning the war that it had started, as it found itself faced with the military and economic might of a UN coalition, in addition to a large contingent of American troops who helped repulse the North Korean onslaught. In addition, after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, the USSR no longer saw any promise in continuing to support the war. The latest flight tactics of the UN coalition pilots were able to inflict great losses on the Soviet MiG-15 fleet through the end of the war. In just three weeks of May 1953 (from the 8th to the 31st), 56 MiG-15s were confirmed shot down for the loss of only one American F-86 Saber fighter. Soviet pilots left the Korean theatre of operations and no longer took to the skies with their jets, leaving some of them in North Korean hands.

Already after the end of the hot phase of the war, a working version of the Soviet jet plane fell into the hands of the UN coalition. On September 21, MiG-15 #2057, piloted by a North Korean pilot Lt. No Kum-sok, landed at the Kimpo Air Base on the outskirts of Seoul, South Korea. He decided to escape from the communist dictatorship using the fastest means – a military jet. As he sat on the tarmac of his enemy’s airfield, Lt. Kum-sok was not even aware that the US had offered a reward of $100,000 for a serviceable MiG-15 as part of a previously planned operation codenamed Moolah. In just one day, the lieutenant became not just a free man, but also a rich man.

Source: National Museum of the United States Air Force

As for the future fate of the DPRK, after the end of the hot phase of the war, the country was preserved for decades and was fueled by the ideas of revanchism and the constant mobilization of the population under communist dictatorship. While the USSR would bow out of the Korean war, although the USSR came out of the conflict, the de facto existence of the DPRK as an enclave of communism in the East was just as beneficial to the newly-consolidated People’s Republic of China as it was to the Soviets. This policy was not changed even by the ascendance of Nikita Khrushchev and the beginning of the official recognition of Stalin’s crimes and condemnation of his cult of personality and the cannibalistic regime he introduced.

Starting at the end of the 1950s, the USSR actively promoted the development of the DPRK’s nuclear program, exchanging missile technologies with the Juche regime and sending its nuclear specialists to the country.

Start of the nuclear program: Nuclear center in Yongbyon

The de jure beginning of the DPRK’s nuclear program took place in 1956, when the USSR and North Korea signed their first agreement on the mutual training of nuclear specialists. Of course, this training was only mutual on paper, because Soviet scientists acted as instructors for the North Koreans, who had rather indirect knowledge about nuclear fusion.

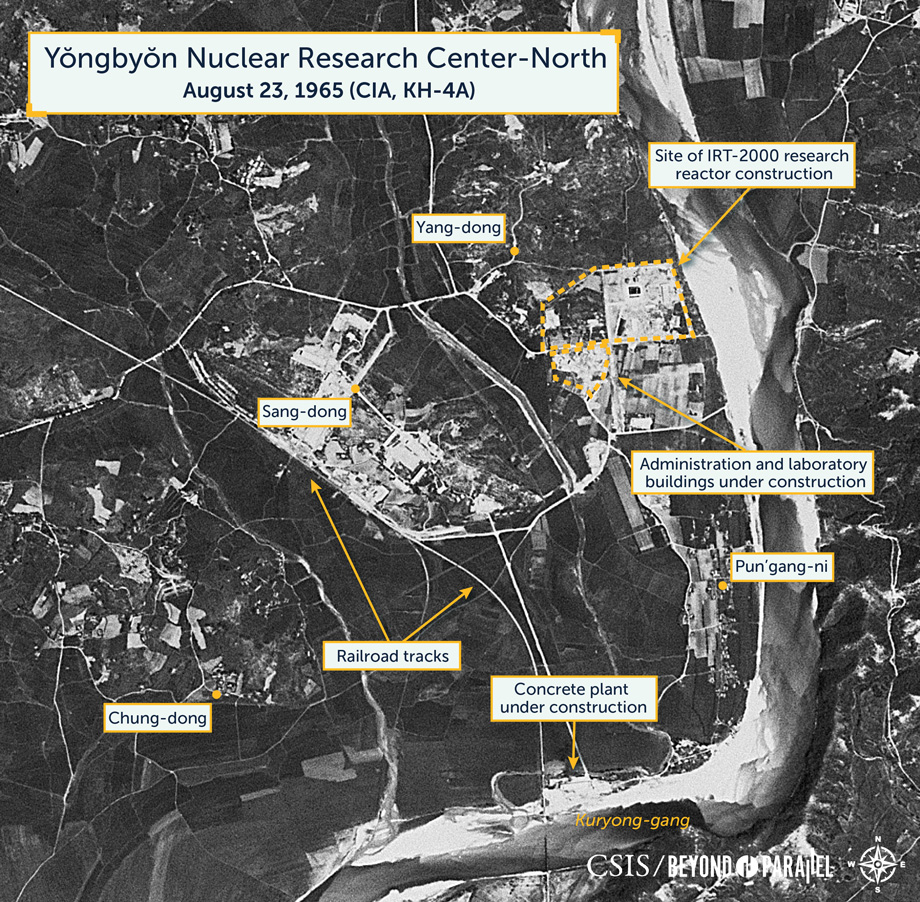

Three years after the signing of this agreement, the DPRK concluded another document with the USSR, this time on cooperation in the peaceful use of nuclear energy. This agreement marked the beginning of the construction of the country’s first nuclear research center, which was built around Yongbyon. It was there that the DPRK’s first nuclear reactor, the IRT-2000, was built by Soviet specialists. The North Koreans would start nuclear fission experiments as early as 1965, as soon as IRT-2000 reached its minimum power of 2 MW.

The IRT-2000 was a basin-type research nuclear reactor, operating on light water (beryllium water), which acted as an electron reflector. It was a low-power reactor, and could produce only 4 MW of energy at the peak of its capacity, which was not enough to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons.

In the mid-1960s, when the Yongbyon Nuclear Center had just begun its work, it was barely a square kilometer in area. However, in the late 1980s, when the world no longer had any illusions about the DPRK’s development of its own nuclear program, it had grown to 3.5 sq. km. The infrastructure at Yongbyon included an extensive network of railway tracks, support buildings, experimental laboratories, and living quarters for station personnel located in the two previously-abandoned villages of Sandong and Yangdong.

Despite the Soviet-North Korean nuclear cooperation, Moscow was not too interested in Pyongyang producing nuclear fuel on its own. The Soviet ambassador to the DPRK, Vasyl Moskovskii, repeatedly emphasized that from an economic point of view, it would be much more profitable for North Korea to purchase pre-enriched nuclear fuel from the Soviet Union, in order to further process it into electricity using the IRT-2000. Even a small amount of Soviet uranium would be enough for North Korea to cover all of its internal energy needs. Instead, the “Northern comrades” persistently argued to their Soviet counterparts that a small share of uranium would not be enough, and that their country’s main goal was to accumulate its own nuclear fuel. Of course, the Soviet ballistic missiles which North Korea would later arm with nuclear warheads first arrived in the country in the early 1960s.

Transfer of the first ballistic missiles

In the 1960s, the USSR supplied North Korea with the first batch of 24 operational-tactical 9K52 Luna-M (NATO classification: FROG-7) missile systems to strengthen the communist regime’s defense capabilities. These missile complexes used unguided 3P-11, 9K21, 9M21, R-65 (FROG-7A), 9K52, 9M52, and R-70 (FROG-7B)ballistic missiles, and could be mounted on both wheeled and tracked chassis (like the 2K- 6 Luna) which increased their mobility.

The Luna-M’s unguided ballistic missiles flew on solid fuel and used a high-explosive fragmentation warhead. The range of the Luna-M missile systems was a relatively low 40 km, which was obviously not enough for offensive combat operations. In addition, unguided ballistic missiles had insufficient accuracy, as with incorrect targeting, its error range could be from 400 m to several kilometers.

However, after the Cuban Missile Crisis, which almost led to the start of a hot war between the USSR and the USA, the Soviets became more cautious about the direct supply of weapons to friendly regimes, including the DPRK. In 1976, when North Korea received a new batch of Soviet R-17 liquid-fuel ballistic missiles (NATO classification SS-1c Scud B) for the Elbrus operational-tactical missile systems, North Korea was only able to procure them from Egypt, which was friendly with the USSR at the time.

When the world learned that Pyongyang had acquired R-17s, Moscow categorically denied that they had done so with Soviet permission, but it is simply impossible to imagine that the Egyptian government would have dared to go against the Kremlin’s position on the issue of transferring its weapons to third countries. In exchange for the missiles received from Cairo, the DPRK presumably agreed to provide military support to Egypt in its confrontation with Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

The range of the new P-17 was 300 km, which put almost the entirety of South Korea in range of missiles launched from the border. The DPRK’s acquisition of these missiles seriously aggravated the security situation between the two countries of the Korean Peninsula, which were still formally at war.

North Korea’s possession of R-17s was even further threatening in the context of Pyongyang’s first steps in the 1970s to develop its own nuclear weapons. However, while it hoped for support from Beijing and Moscow, North Korea did not wait for its main allies’ approval to develop nuclear weapons. Indeed, neither the USSR nor the PRC wanted to have even a friendly country equipped with weapons of mass destruction on their borders. However, while Moscow and Beijing may have held this position in the 1970s, the future would bring drastic changes.

With or without nuclear warheads, the presence of the P-17 in the DPRK freed the hands of North Korean missile specialists to modernize their ballistic missiles (North Korea had developed these specialists since the 1960s). It was the P-17 that was used as the basis for the first North Korean-made missile, the Hwasong-5 (NATO classification: Scud-B), which was produced in the DPRK in the mid-1980s. With it, the DPRK began the production of its own ballistic missiles, and since that point, North Korea’s stocks of ballistic missiles have been steadily accumulating. They have constantly reminded other countries in the region about this fact with numerous missile tests.

Start of own production: the first Hwasong

Soviet missile technology and China’s full diplomatic support proved effective: North Korea managed to modernize the rocket engine, guidance system and airframe of its missile, thereby increasing its range to 330-340 km. It was suggested that both countries (the USSR and the PRC) would benefit from the transformation of the DPRK into a missile warehouse, from where, if necessary, missiles can be exported to the whole world, without either country playing a direct role.

The first Hwasong-5 missile tests began in 1984, and two years later, the missile entered service with Pyongyang’s missile forces. The Hwasong-5 was able to carry a warhead weighing up to one ton. Since the 1990s, after completing a series of tests, the North Korean dictatorship has launched mass production of ballistic missiles, bringing their number up to approximately 300 producing several dozen launchers for them.

The appearance of Pyongyang’s own ballistic missiles significantly changed the DPRK’s position in East Asia. From now on, the Juche country no longer hesitates to threaten its southern neighbor with a “missile attack,” ignoring the diplomatic and sanctions pressure from many UN countries.

Along with its use for purposes of intimidation, North Korea’s development of the Hwasong 5 allowed Pyongyang to earn money by exporting its missiles to other countries. In the following decades, the DPRK would sell to the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, the Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Vietnam, and even Egypt, to which the previously provided Soviet missiles boomeranged back, but in a new wrapper.

Thus, without the participation of the USSR and its missile technologies, most of the countries that today supply missiles to kill Ukrainians simply would not have their own missile production (or would have only been able to develop it at a rather mediocre level). The Soviet colossus seems to have made an investment in the future, passing onto its partners and satellites long-range missiles which would later be converted into weapons of mass destruction.

Third countries would buy not only North Korean missiles, but also the technologies by which they were built. With the direct support of China, Pakistan was able to gain access to the missile technology used in the construction of the Hwasong-5. In the future, Pakistan would use the experience of Chinese and North Korean missile specialists to create its own missile fleet of short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, which it still has in service.

Iran followed the same path. In 1985 alone, the country purchased 90 to 100 Hwasong-5s from the DPRK for a total of $500 million. In Iran, the Hwasong-5s were designated Shahab-1s. As you can see, the Soviet R-17 missile underwent mass distribution, reaching almost every continent of the world (everywhere where Moscow had its interests).

The appearance of the Hwasong-5 in North Korea’s armed forces coincided with the final construction of the nuclear research center in Yongbyon, which took place in 1985. A new nuclear reactor with a graphite moderator opened the way for North Korea to produce plutonium, which serves as fissile material for nuclear warheads. The completion of the first reactor with a graphite moderator marked the start of the construction of another, more powerful nuclear reactor of a similar type.

Despite its membership in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which Pyongyang joined on December 12, 1985, Pyongyang’s testing and development of nuclear weapons has not stopped. The US was able to prove this only in 1989, when spy satellites clearly showed North Korea’s missile infrastructure and launch shafts. In the future, the increasing level of the nuclear threat even led to North Korea leaving the IAEA in 1994, after having joined it in 1974, thereby starting the nuclear blackmail which the country has been engaged in in one way or another ever since. Withdrawal from the IAEA and subsequent threats to end participation in the TPNW were an ambiguous political signal from the Juche country about what was really behind the DPRK’s nuclear ambitions — a peaceful atom was out of the question.

As for the Hwasong-5 itself, the missile was modernized throughout its life cycle, including in 1989, when it was replaced by a new version, the Hwasong-6. It was still the same Hwasong-5 (or rather Scud-B) with the only significant difference being an increase in range to to 500 km. North Korean engineers managed to achieve this by reducing the warhead (from almost 1 ton to 770 kg), as well as by lengthening the missile body, which significantly improved its ballistic characteristics.

But despite the significant increase in the missile’s effective range, North Korean engineers did not make any modifications to the Hwasong-5 guidance system, which meant that the missile’s error range could be as high as a kilometer, making it impossible to use for accurate strikes. It became obvious that in order to increase accuracy, North Korea needed new developments in missile technology, to which Pyongyang was able to get access in the mid-1980s and early 1990s.

The first medium-range missile: NoDong-1

The next generation of North Korean missiles, the Hwasong-7, was strikingly different from its predecessors. While it still used four liquid propulsion units using modernized replicas of Soviet 9D21 rocket engines, the elongated body of the R-17 rocket made it possible to significantly increase its aerodynamic stability without the need for significant modification of its active stabilization system. As a result of the changes, the Hwasong-7 was even renamed NoDong-1. The name change indirectly confirmed speculation that the new missile was radically different from anything that was previously in the North Korean ballistic arsenal.

The NoDong-1 missile was also North Korea’s first in the medium-range category, which includes missiles with ranges between 500 and 1500 km. However, the NoDong-1 test trials, which took place in May 1990, were not successful, as the last missile exploded on the launch pad during launch. North Korea’s neighbors breathed a sigh of relief, because it seemed that the new medium-range missiles were nothing more than a myth constructed by the Juche regime’s propaganda. However, the North Koreans themselves were convinced otherwise, so they sought to find out the reasons for their fiasco.

In May 1993, exactly three years after the first launch attempt, the DPRK resumed NoDong-1 tests, with both test launches producing missile flights of over 500 km. This distance was impressive, but it turned out to be only the beginning – after studying the missile and its aerodynamic properties, the US came to the conclusion that the NoDong-1 was capable of covering a distance of 1,500 km, thus threatening not only its southern neighbor, but also other American allies in the East Asian region, primarily Japan, with which the DPRK had an old enmity. These alarming predictions would eventually come true, as subsequent upgrades of the NoDong-1 ballistic missile, which appeared in the North Korean arsenal in the late 1990s and early 2000s, were able to travel from 1,000 to 1,250 km.

The success of the second round of NoDong-1 tests rekindled interest from Iran and Pakistan, who subsequently bought licenses for the NoDong-1, releasing it under the names Ghauri-1 (Pakistan) and Shahab-3 (Iran).

During the 1990s, North Korea also managed to seriously improve the reliability of its missiles. While until 1994, every second ballistic missile launched by the DPRK would fail to achieve its goals, things began to change in the second half of the decade. Between 1994 and 2011, the failure rate of refusals fell to 23%. North Korean missile engineers learned from their mistakes, and with the direct participation of their Chinese colleagues, who at the turn of the millennium began to join the DPRK’s missile program as they modernized their own missile stocks, also entirely based on Soviet missile technologies.

This led to the DPRK demonstrating another medium-range ballistic missile, the Taepodong-1, in 1998. Unlike previous North Korean ballistic missiles, the Taepodong-1 had three stages, which, in theory, even allowed it to launch satellites into orbit. The first use of Taepodong-1 for these purposes took place on August 31, 1998, during the attempt to deliver the first North Korean satellite into orbit – Kwangmyŏngsŏng-1 (translated “Bright Star”). Pyongyang officially reported the successful launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-1 into orbit, but in the months that followed, no countries were able to confirm its presence in orbit.

Even the collapse of the USSR did not affect Moscow’s cooperation with Pyongyang in the missile field. Formally, the newly-created Russian Federation considered itself to be a democratic country (an ideology which the Juche regime officially virulently opposed), but in the mid-1990s, the North Korean government entered into an agreement with Russia’s Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau, signing a contract for the participation of Russian specialists in the design of a new North Korean ballistic missile. In order to reduce attention to this agreement, the terms of the contract stated that the new ballistic missile was designed specifically for peaceful space launches and the delivery of payloads into orbit. However, the entire forty years of North Korea’s existence testified to the fact that the country seeks to turn any peaceful technology into a military one in a matter of years.

It is this contract from the 1990s and the subsequent involvement of Russian specialists in the development of a new ballistic missile in the DPRK that would lead in the next millennium to the appearance of North Korea’s Hwasong-10 missile, capable of covering a distance of 2,500 to 3,500 km (depending on the warhead). You can read about that in the second installment of our series on the North Korean missile program.