In the first installment of this series, we discussed how missile and nuclear technologies first arrived in North Korea. A number of agreements on mutual cooperation with Soviet and Chinese missile specialists led to the DPRK entering the new millennium armed, technically prepared, and full of desire to regain full control over the Korean peninsula.

But first, the Juche country decided to “repay its debt” to its past sponsors. Unexpectedly, it turned out that the stockpiles of weapons (in particular, missiles) which the DPRK has been accumulating for almost 40 years is enough not only for their regime’s own needs, but also to sell to third countries, primarily its recent investors.

The partnership continues, and the DPRK is already present in Earth’s orbit: in 2023, the first North Korean spy satellites began to appear over the Korean Peninsula. We can see through the development of North Korea’s missile and space program that a clear anti-Western alliance is taking shape.

The illusion of silence

It may seem strange now, but the DPRK entered the new millennium as a negotiating partner — in mid-September 1999, American diplomats were able to pressure Kim Jong Il into not conducting new tests of medium-range ballistic missiles (up to 5,500 km).

For its part, the US agreed to provide security guarantees and to significantly ease the sanctions pressure on North Korea, which suffered from a colossal economic and food crisis during the 1990s. At its peak, this crisis even led to a genuine famine, from which, according to various estimates, 250,000 to 3 million citizens of the country died (1.25-15% of the entire population). Achieving this compromise, which allowed for the reduction of military expenditures, was very beneficial for Pyongyang, because it got the opportunity to focus on solving internal problems due to concessions in the region. However, the arrival of George W. Bush in the White House changed everything radically.

A series of mutual diplomatic spats and the American invasion of Iraq had a lot to do with it. Since 1999, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had been building relations with Kim Jong Il’s regime in the DPRK in regards to missile development. Moreover, according to CIA reports, Iraq was seeking to sign a $10 million contract with North Korea to receive Hwasong-7 missiles. Thus, when the US launched a military operation to overthrow the Hussein regime, North Korea actually sided with the beleaguered dictator.

After the defeat of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, North Korea began stepping up its criticism of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which expressly prohibited Pyongyang from enriching uranium and producing plutonium. New, more powerful nuclear reactors came to North Korea from Pakistan in exchange for NoDong-1 missiles. Cooperation in missile development between Pakistan and the DPRK began in the 1980s, when both countries used their specialists in the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988, at that time on the side of Iran. The supply of new reactors showed that cooperation between Pakistan and North Korea had continued into the new century.

In 2002, the US announced, based on their intelligence, that the DPRK was continuing to produce and stockpile plutonium-239 and at that time already had from 7 to 24 kg of the fissile material, which it could use in the production of its own nuclear weapons.

In response to the accusations at the beginning of 2003, the DPRK officially announced its withdrawal from TPNW. The country had threatened to take this step back in the early 1990s, but while earlier it may have been an obvious bit of political blackmail against the US and its allies in the region, the process started in 2003 was significantly different from what the world had seen before, as the exit was official. North Korea felt more and more independent both in the accumulation of nuclear weapons and in the production of its own fleet of means for their delivery.

North Korea expands its arsenal

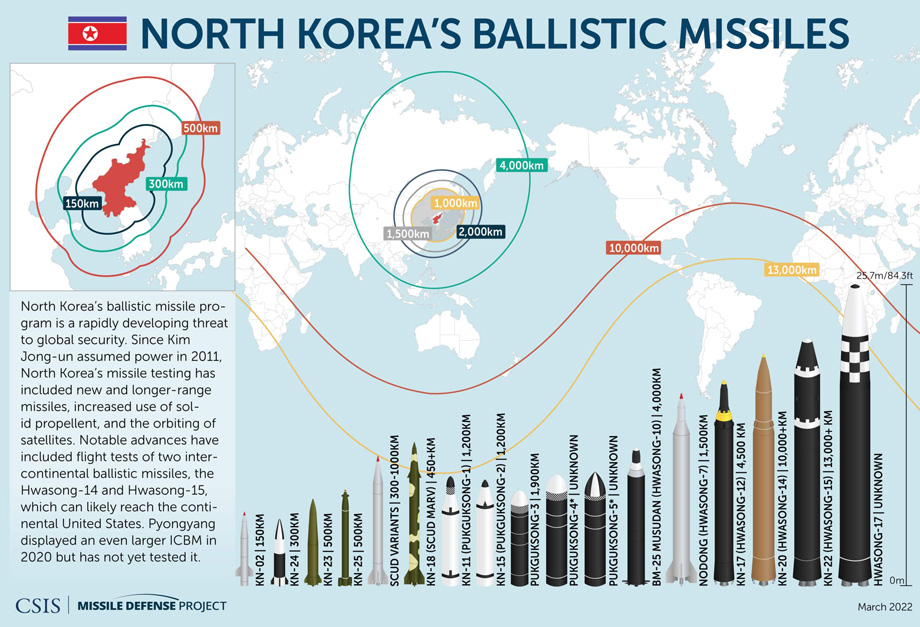

North Korea spent the first decade of the new millennium adding new missiles to its arsenal. First was the Taepodong-2, which the DPRK first tested in 2006. Immediately perceived by the US as a new intercontinental ballistic missile (with a range up to 10,000 km, according to US estimates), the Taepodong-2 was actually intended purely for space launches, which was officially recognized by the US Department of Defense in 2012. The military came to this conclusion based on many factors, including the testimony of a North Korean scientist involved in the development of the missile who fled to South Korea.

It was not only the Taepodong-2 which was tested in the early 2000s. Obsolete missiles based on the Soviet R-17 (Scud-B) also needed replacement. In 2019, the DPRK would begin testing the new KN-23 and KN-25 short-range (500 km) solid-fuel ballistic missiles. The first tests showed that these new missiles were more economical, reliable, and accurate than the Hwasong-5 and Hwasong-6.

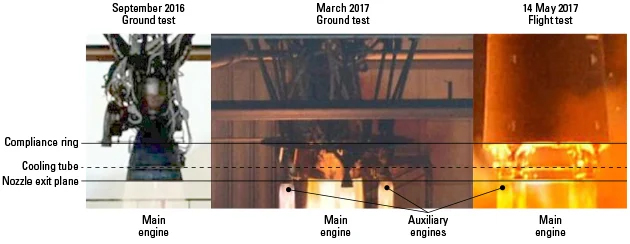

In April 2017, Pyongyang conducted the first tests of its new Hwasong-12 (KN-17) missile, capable of covering a distance of 4,500 km, which is more than three times higher than that of the NoDong-1 put into service in 1994. Again, the North Koreans relied on Russian equipment, since the main thrust of the Hwasong-12 came from a replica of the RD-250 liquid rocket engine, which was used on Russian R-36M missiles (NATO classification SS-18).

The North Korean replica of the RD-250 engine was much more powerful than its replica of the Soviet 4D10 which powered its Hwasong-10 missile, whose test launch had taken place a year earlier in 2016. North Korea also installed versions of Soviet rocket engines on their Pukguksong-1 (KN-11) submarine-launched ballistic missiles, which they began testing in 2014.

The 4D10 engines were not bad for their time, but they did not allow rockets to fly long distances. However, North Korea learned suspiciously quickly to exploit their potential in its missiles, making significant progress in improving the design of the Pukguksong-1 in just two years. Test launches from 2016 showed a 16-fold increase in the missile’s flight range (from 30 to 500 km), which allowed them to reach the target area of Japan’s air defense systems.

Since 2011, when Kim Jong-un took over as dictator of the DPRK, the failure rate of North Korean missile launches has also decreased sharply down to 15%. Overall, since 2012, Pyongyang has already conducted 214 missile tests (as of January 2024), significantly higher than any 12-year period prior to that.

It is worth noting that it was the successful test experience of the Hwasong-12 that opened the way for North Korea to develop its first domestically-produced intercontinental missile, the Hwasong-14 (KN-20). Pyongyang began testing it in July 2017. The missile’s aerodynamic design allowed it to cover a distance of 10,400 km. This signaled that North Korea finally had a missile delivery system capable of reaching the US West Coast. The appearance of the Hwasong-14 and the Hwasong-15 (with a flight range of more than 13,000 km) would force the United States to accelerate the improvement of its ground-based anti-missile defense system (GMD), currently the only system capable of protecting the US from long-range missiles.

But let’s return to the modifications of Russian rocket engines on North Korean missiles, since as the case of missile transfers to Egypt in the 20th century showed, this story may have mediators who may not be obvious at first glance.

Yesterday’s customer is today’s supplier: strengthening cooperation with Iran

Once upon a time, Iran was one of North Korea’s first missile customers, purchasing about 100 of Pyongyang’s Hwasong-5s. For many years, researchers studying Iran’s possible cooperation with North Korea in the missile field viewed this process purely through the prism of commercial orders. However, the devil, as always, is in the details, namely in the international agreements between the two pariah countries.

In September 2012, the DPRK and Iran concluded an agreement on scientific and technological cooperation. A standard document at first glance, it actually led to a number of rather threatening steps – in the more than ten years since the agreement was signed, both countries have created a number of scientific groups and laboratories, starting the process of exchanging scientific and technical experience, in particular regarding missile production.

Since 2005, Iran has been increasing its cooperation with Russia in the rocket and space industry. Thus, the bilateral agreement between Tehran and Pyongyang has provided an opportunity to gain at least partial access to joint Iranian-Russian developments in the missile industry. It was likely through Iran that North Korea acquired the lion’s share of knowledge about the technologies on which Russian ICBMs were built.

In the photo: Kim Jong Un in front of a Hwasong-15 missile complex

Only the position of Moscow itself remained uncertain in this story. In the early 2010s, its position in the world was still teetering on the edge of moderation, and there was little pronounced anti-Western rhetoric. However, in only a few short years, Russia’s participation in supporting the regimes of Iran and North Korea would no longer be considered a coincidence. It has become increasingly apparent that by supporting both countries’ missile programs, the Kremlin is strengthening its potential allies in the future global confrontation between East and West.

So, while some countries have given North Korea access to their own missile technologies, others have strictly prevented such attempts. Several such cases have occurred during Ukraine’s independence, when, through espionage, the DPRK tried steal missile technologies from the Dnipro-based Pivdenmash and Pivdenne Design Office to obtain schematics of the above-mentioned RD-250 rocket engines, which were manufactured in the companies’ workshops.

Espionage scandals and expulsion of criminals from Ukraine

After the collapse of the USSR, the Russian and Ukrainian missile industries largely merged with each other. A number of joint projects (such as cooperation in the production of Ukrainian Zenit-3SL rockets for the Sea Launch platform) only emphasized the utility of unbroken industrial and logistical chains between the two former Soviet republics.

It was in the 1990s that the first reports emerged about attempts by North Korean spies to get hold of technical documentation and drawings of rocket engines produced by the Dnipro-based Pivdenmash and Pivdenne Design Bureau. Kyiv officials announced that these plots were successfully detected and disrupted at the time.

In 2012, the DPRK again aimed to obtain Ukrainian missile technology, but now everything was not limited to espionage scandals in the press. Thus, the two North Korean spies tried their best to establish relations with Pivdenmash employees, offering to purchase schematics of the rocket engines produced by the enterprise. . In June 2012, this led to the arrest of the perpetrators and a subsequent diplomatic scandal which resulted in the North Korean ambassador and almost the entire staff of the North Korean embassy in Ukraine being expelled from the country.

However, the attempts to steal Ukraine’s technical documentation for its rockets did not stop there. For a third time, in December 2015, two North Korean diplomats who arrived in Ukraine from Belarus, wanted to get access to Ukrainian missile technologies during one of their official visits. But even these sad spies were exposed and arrested.

It should be noted that despite Kyiv’s firm position on non-distribution of its own missile technologies to third countries, a corruption component cannot be ruled out. These are the assumptions made by analyst Michael Elman in his report The Secret to North Korea’s ICBM Success, published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies on August 14, 2017.

To confirm his assessment, Elman pointed out that the nozzles of rocket engines installed on North Korean missiles very strongly resemble the design of the RD-250, which was produced by the Ukrainian rocket company.

In addition, the breakdown of contacts between Ukraine and Russia after the start of Russia’s armed aggression and annexation of Crimea threatened to put the Ukrainian missile company on the verge of bankruptcy, and raised the risk of certain disgruntled employees looking for easy money by selling secret missile technologies to third countries. But the official management of Pivdenmash and the Pivdenne Design Office, and later Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, denied the analyst’s accusations.

And even if we assume that the DPRK could have corruptly obtained a certain share of the schematics from the Dnipro-based Pivdenmash and Pivdenne Design Office, it should be understood that our country was by no means among the first to contribute to Pyongyang’s development of its deadly long-range missile arsenal.

Bypassing its own sanctions: why is China strengthening North Korea?

In 2003, the United States criticized Beijing’s export policy, by which a group of Chinese contractor companies organized the supply of missile components to a number of countries, including North Korea. It is worth noting that the DPRK is the only country with which the PRC is in a defense alliance after the signing of the Sino-North Korean Treaty of Friendship, Community, and Mutual Assistance in 1961. Starting from this time, China has maximally contributed to the strengthening of its friends in Pyongyang, both in terms of circumventing Western sanctions, and by revitalizing the import of Chinese military and technical technologies into the country.

It is worth noting that by supplying missile equipment to the DPRK, China violated a number of its own restrictions, which it imposed on itself in 2002. Beijing then joined UN restrictions and adopted several laws on its own export controls aimed at non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (including nuclear, chemical, and biological arms) to third countries.

With evidence of violations of these rules, in July 2003 the United States imposed a series of sanctions against five Chinese companies that were involved in a scheme to circumvent sanctions restrictions. They included the China Precision Machinery Import/Export Corporation (CPMIEC), Taian Foreign Trade General Corporation, Liyang Yunlong Chemical Equipment Group, China North Industries Corporation (NORINCO), and Zibo Chemical Plant. The North Korean company Changgwang Sinyong Corporation, which, according to foreign intelligence, was connected to the supply of Scud-B (Hwasong-5) missiles to Yemen in 2002, also fell under American sanctions.

Sanctions did not stop China’s support for North Korea and Pyongyang’s production of its own nuclear weapons. Despite the fact that the weapons of mass destruction were located literally on the Chinese border, they were nevertheless located in a friendly communist regime, whose inviolability the PRC was keen to guarantee. In implementing this policy, China even found itself in a strange position – the country had to again violate its own sanctions, imposed on North Korea after another round of nuclear tests, which it had been carrying out since 2006.

China’s deliberate ignoring of the DPRK’s nuclear weapons development is not only for political purposes – Chinese front companies make good money from contracts with the Juche country, and a number of other shady schemes are clearly aimed at laundering money (mainly cryptocurrency) which is stolen by North Korean hackers. According to US estimates, the amount of such revenues only in recent years could be as high as $3 billion. It is no surprise a boom in the growth of the DPRK’s missile sector has coincided with this period.

The physical presence of Chinese equipment is easy to see on North Korean mobile missile launchers, because even the chassis on which they move are made in China. Beijing officials denied this with statements at the UN, saying that it supplies heavy trucks to North Korea exclusively for the country’s logging companies. The PRC seeks to deflect suspicions from the UN by all possible means, sometimes reaching the point of absurdity in this matter. Thus, in response to a recent call for China to conduct its own investigation into a possible violation of export controls and sanctions against the DPRK, the Chinese replied that it could not proceed with the case, because the names of all companies involved in shady schemes were provided to it only in English and Korean.

Such frank mockery of the official regulatory bodies did not lead to anything other than periodic “letters of indignation” from UN countries supporting the sanctions pressure on the DPRK. Therefore, North Korean ships still enter Chinese ports without any obstacles, and only the parties involved in this process know exactly what is being transported in their cargo holds. One thing is clear – both countries continue to promote this activity at the highest level.

Presence in space: satellites in exchange for missiles?

In our previous installment, we discussed how North Korea’s first attempts to put their own satellite into orbit began in 1998. At the end of the last century, Pyongyang announced that it had managed to deploy its Kwangmyongsong-1 satellite into orbit, but independent observers concluded that this was most likely a bluff, since the device has never actually been observed.

Since the beginning of the new century, the DPRK has tried several times to send its own artificial satellite into orbit, and also failed. In April 2009, a three-stage launch vehicle Taepodong-2 (Unha-2), modified for the needs of orbital launches, was launched from the Tonghe missile complex, with the Kwangmyongsong-2 satellite on board. However, the rocket failed to separate its stages, causing the payload to be lost.

In 2012, North Korea made two more attempts to deploy satellites. And while the launch of Kwangmyongsong-3 on April 13 again turned into a fiasco, the country managed its first success in December. Pyongyang proudly announced that it had put a surveillance satellite into orbit, but many experts have concluded that it does not even have a feedback system with the Earth. However, the event itself remained an established fact — the DPRK has the ability to deliver satellites into orbit.

After the first success in orbit, the DPRK established a new structure – the National Aerospace Development Administration. From now on it iswill take over issues of space exploration, as Pyongyang never gets tired of asserting, “exclusively for peaceful purposes.” The pace at which the new agency worked turned out to be quite slow — for almost 10 years, the country stopped trying to launch new satellites, resuming exams only in 2023.

It seems that the ten-year period of lull in satellite launches was no accident, because the beginning of the Russian Federation’s full-scale war against Ukraine marked a new stage in the DPRK’s military partnership with Moscow. As a result, the Russians have received artillery ammunition and even a number of operational-tactical and short-range missiles, which were later used for attacks on Ukraine. According to US military intelligence agencies, these were Hwasong-11 ballistic missiles (NATO designation: KN-23 and KN-24). Experts came to these conclusions after studying photos of missile parts provided by Ukraine which clearly showed fragments of a ring and a thruster blade very similar to those that North Korea installs on its ballistic missiles.

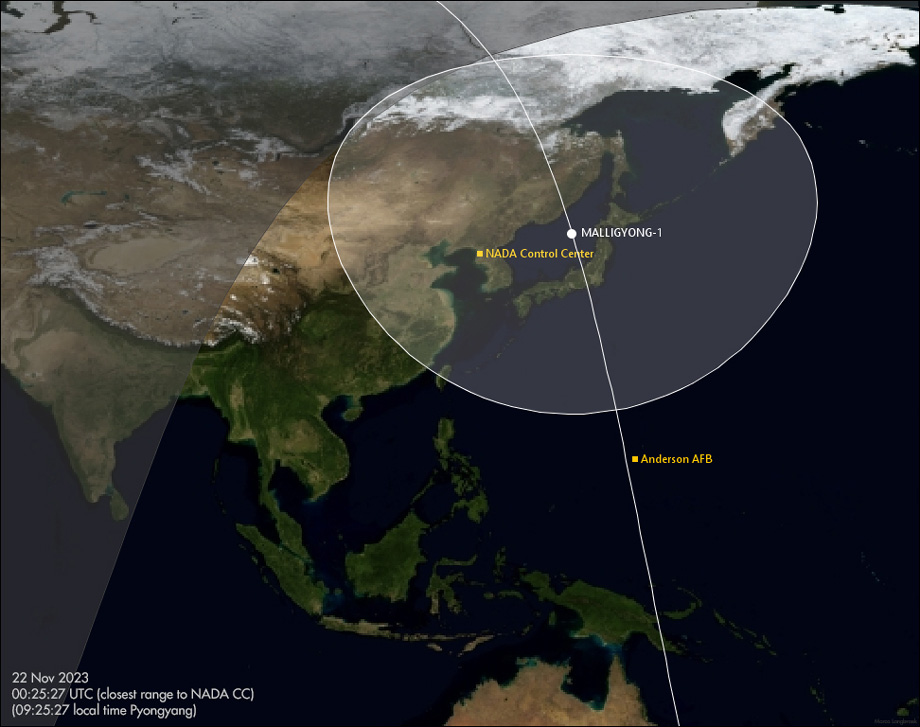

North Korea eventually waited to be rewarded for the weapons it now supplies 7,000 km from its territory. After two unsuccessful attempts last year (May 31 and August 24), the DPRK did manage to put its first military intelligence satellite into orbit, the Malligyong-1, which reached orbit on November 21, 2023 aboard a Chollima-1 rocket.

It is interesting that between the second and third attempts, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un made a visit to Russia, the main part of which was held with much fanfare at Russia’s main spaceport.

As a result of the meetings, the leader of the DPRK received a promise from Putin for Russian assistance with the production and launch of the next North Korean satellites. Just two months after this event, the DPRK announced that the first satellite images taken by Malligyong-1 had landed on Kim Jong Un’s desk. Pyongyang claimed that a number of US military bases deployed in the East Asian region were recorded on them, including military facilities on the island of Guam, the Navy base in Pearl Harbor, as well as the US Air Force base in Hickam (Honolulu).

Analyzing the success of its northern neighbor, South Korea concluded that Russian missile experts had most likely provided their North Korean counterparts with extremely important recommendations regarding the separation of missile stages, a key stage that the DPRK’s missile program had struggled to handle for so long.

Over the years of development of its missile program, the DPRK delivered more than 1,200 domestically-produced ballistic missiles to its customers in Iran, Pakistan, Yemen, the UAE, the Republic of Congo, and Russia. At the same time, the Juche country continues experiments with obtaining enriched uranium and plutonium-239, and according to a 2021 RAND report, it may have more than 200 nuclear warheads in its arsenal by the end of 2027.

The situation becomes even more threatening in light of North Korea’s recent statements regarding the termination of the inter-Korean military agreement, perhaps the last straw of hope for a peaceful coexistence between Pyongyang and Seoul. North Korea’s threats of a future war with South Korea are gradually moving from theory to reality. Many traditionally anti-Western countries have had a hand in this — so the war dog, which has been fed rocket technology for more than 60 years, is about to be let off the chain.