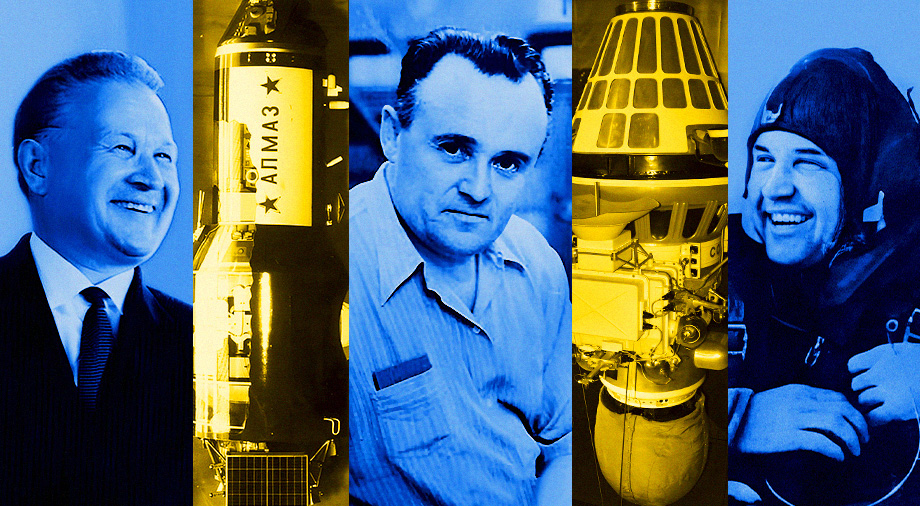

Last time, we talked about the Ukrainians who were among the first cosmonauts of the USSR. However, the contribution of Ukrainians to the development of cosmonautics was not limited to them. At least three of our compatriots played a decisive role in the design (Volodymyr Chelomei and Serhiy Korolyov) and operation (Georgiy Dobrovolskyi) of the world’s first orbital station, the Salyut-1.

This article is a long-awaited continuation of the story about outstanding Ukrainians who etched their names in the world history of space exploration.

The first concepts of orbital stations

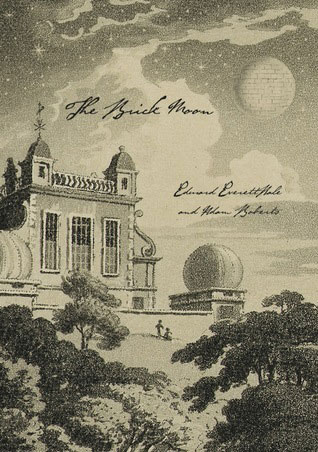

Mankind dreamed of the idea of orbital stations almost 100 years before the beginning of the conquest of space. In 1869, the American science fiction writer Edward Everett Gale drew a description of a similar apparatus for long-term human habitation in space. His short story The Brick Moon is about a 200-pound, man-made sphere made of bricks that was planned to be launched into a 4,000-mile high Earth orbit to create a navigation router. The project’s designers intended for the sphere’s bright glow to be visible in the night sky. However, due to engineering negligence, the brick sphere suddenly flies off into space with its crew still aboard.

The story has a happy, expected ending, with the crew being rescued. However, as we will see later, real orbital stations were not so safe.

Source: goodreads.com

The first people to begin doing actual scientific work on this idea of science fiction were the Russian theoretician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and the German rocket engineer Herman Obert. In their writings and reflections, they argued for the inevitable appearance of populated orbital stations for future space exploration and even described the basic principles of their operation and management.

Outstanding designer Volodymyr Chelomey

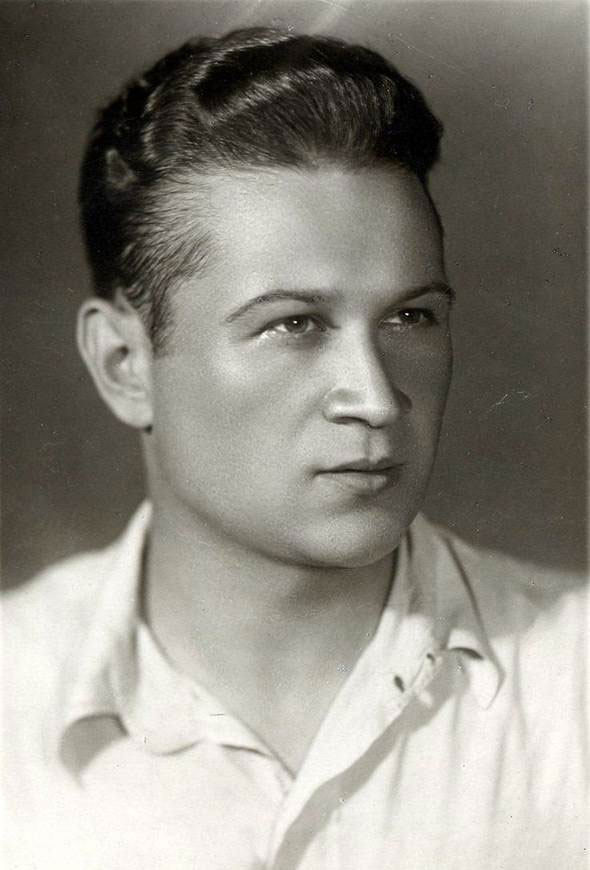

Soviet aerospace engineers were the first to turn the ideas of the theorists of the past into reality. One of them was Volodymyr Chelomey, who was born in the Polish town of Siedlce. His family fled the violence of World War I when he was two years old to the Ukrainian city of Poltava, and later to Kyiv. In 1932, he entered the Aviation Faculty of the Kyiv Mechanical Engineering Institute (later the Kyiv Aviation Institute), from which he graduated early in 1937.

As a student, Chelomey became interested in mathematics, physics, and engineering. He closely studied the theory of oscillations, which gave him a strong understanding of motors. He also worked in quality for the local plant manufacturing motors and components (the modern-day Motor-Sich).

Source: aki.nau.edu.ua

Chelomey’s designing genius really came out during World War I, when developed projectile aircraft for the Red Army. The first tests of these Soviet kamikazes took place at the end of 1944, but the war ended before any of them would see combat. However, it was at that point that Chelomey’s talent was noticed by the top management, thanks to which he was invited to work in the rocket industry in the future.

The start rocket development

Chelomei began the 1950s as a developer of cruise missiles for the Soviet Navy as part of the newly created Special Design Bureau (OKB) No. 52, where he was soon named a general designer.

In the early 1960s, during the golden age of Soviet cosmonautics, his OKB began to manufacture the first satellites (in particular, the maneuverable satellite Polyot-1) and the UR-100 and UR-500 intercontinental ballistic missiles.

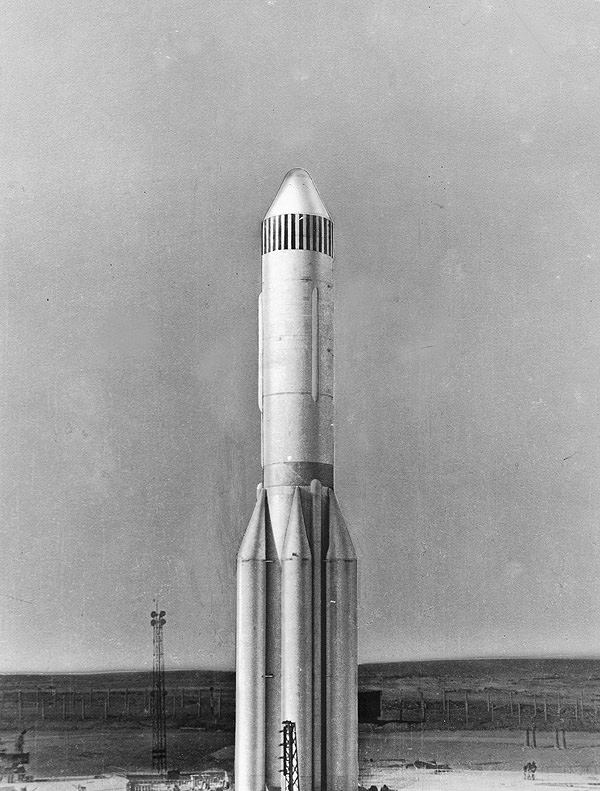

The Proton rocket family Chelomey’s OKB was a true work of engineering art for its time. The first two-stage Proton (which was structurally identical to the UR-500) was later replaced by the more powerful three-stage Proton-K, capable of launching 22 tons of payload into orbit and 5 tons of cargo into an interplanetary transit orbit, namely a lunar one. It was with these rockets that the USSR planned to conquer the Moon before the United States.

Interestingly, while he was overseeing the building of the Protons, Chelomey was in competition with another famous Ukrainian rocket designer, Serhii Korolyov. Korolyov’s N-1 launch vehicle was chosen to demonstrate its capacity for launching spacecraft to the Moon. In many ways, the choice in favor of Korolyov’s project was due to his past merits in launching spacecraft into lunar orbit.

In early April 1966, it was Korolyov’s OKB No. 1 that successfully launched the 245 kg Luna-9 automated interplanetary station (AMS) into lunar orbit, using a single-use Molniya-M four-stage medium-class launch vehicle.

Source: Pline, via Wikimedia Commons

However, Molniya-M was clearly not powerful enough to launch heavier spaceships, including equipped piloted landing modules. This required a fundamentally new and significantly more powerful modification of the launch vehicle.

The choice in favor of Korolyov’s OKB-1 Korolyov, however, did not justify itself. The design of the H-1 involved building the rocket almost from scratch, starting with the main stages and ending with the rocket engines. This circumstance played an evil joke on the Zhytomyr designer, as despite the fact that the N-1 was developed on time, all four attempts to launch it ended in failure. The Soviet lunar program again turned to Chelomey’s Protons, but their full-fledged launch (with a redesigned unmanned Soyuz spacecraft) took place only at the turn of 1969-1970, when the lunar race had already been lost.

This is where the fierce competition between Chelomey’s OKB-52 and Korolyov’s OKB-1 began. Later, the degree of confrontation steadily increased, when the struggle for whose bureau would be the first to develop and launch a manned station into orbit was already in full swing.

From Almaz to Salyut

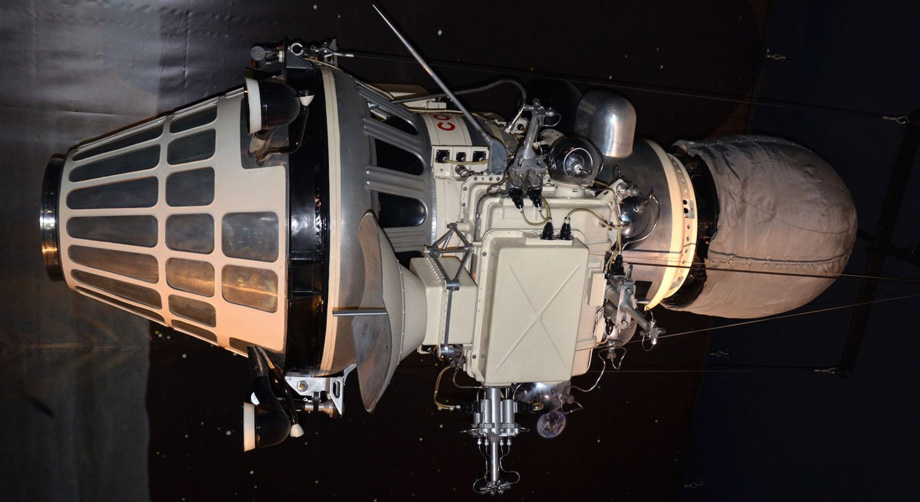

The forerunner of the appearance of the Salyut-1 scientific long-term orbital station was the concept of the Almaz orbital station, which was developed under Volodymyr Chelomey for the Soviet military. According to the plan, the Almaz was supposed to be the first manned orbital reconnaissance station with a crew of two to three cosmonauts and with the possibility of being in orbit for a period of 2-3 years.

The station was supposed to carry out satellite surveillance, radio-electronic reconnaissance, and even, if necessary, take on the role of an orbital command post that could guide the conduct of hostilities from orbit. Planning work for the station started on October 12, 1964.

Work on the Almaz progressed very slowly, primarily due to delays in the development of life support systems and engines. By the early 1970s, the Soviets had barely managed to develop only the orbital station’s main body. That is when the Soviet cosmonaut and rocket engineer Konstantinin Feoktistov, who had been working at Korolyov’s OKB-1 since 1957, had the idea to install the systems and aggregate components of the already-functioning Soyuz spacecraft on the ready-made hull of Chelomey’s Almaz station, thereby speeding up its future launch.

Thanks to his personal connections with Communist Party Central Committee secretary Dmitry Ustinov, Feoktistov managed to bring his project to the highest circles of the USSR. Ustinov liked the idea of improving the station, so he lobbied Feoktistov’s project in the Politburo. The final decision came quickly, as after reviewing the detailed plan of the project, the Central Committee passed a resolution transferring several components of the already-built Almaz orbital station from OKB-52 to OKB-1 for further development and launch of the station.

Chelomey later remarked that this devastating blow “was a pirate raid on my island.” Of course, the Soviet Union’s leadership was never in the mood for long discussions about their own decisions, so the designer had to silently accept this “destiny.”

For the sake of fairness, it should be noted that under Korolyov’s leadership, the project was implemented very quickly. Judging from the standpoint of completion speed, we can confidently say that if it were not for Feoktistov’s initiative, the first ever manned space station would been not the Soviet Salyut-1, but the American Skylab, which NASA planned to launch in 1972 (the actual launch date was May 1973). But the price of this triumph turned out to be too high.

Start of operation

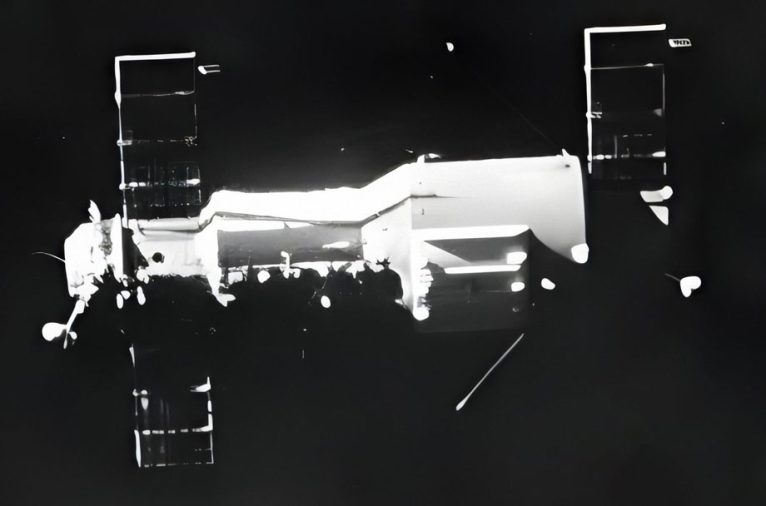

On April 19, 1971, the first ever long-term space station, the DOS-1, which consisted of Salyut-1, Vyrib-17K, and Object #121, was launched into orbit on board a Proton-K rocket from the Baikonur cosmodrome.

Interestingly, the space station was initially to be called Zarya, but that was already the name of a satellite previously launched by China. Therefore, the Soviet press decided to rename it to Salyut, even though it had taken off with the inscription “Zarya” on board. Due to the high secrecy of the project, no photos of DOS-1 have ever been made public.

The Salyut was a brilliant invention of engineering thought of that time. It was planned to remain in orbit for half a year, with the possibility of accommodating a crew of three cosmonauts for up to three weeks.

The crew of the Soyuz-10 spacecraft, launched on April 24, 1971, five days after the launch of Salyut-1, was supposed to be the first people to board the station, as soon as it entered working orbit. It included Soviet cosmonauts: Kazakhstan-born Vladimir Shatalov and Russians Alexey Yeliseyev and Nikolai Rukavishnikov.

The crew of the Soyuz-10 was not destined to come aboard the Salyut-1 due to docking problems that arose shortly after approaching the station. Despite the fact that the pin docking of the spacecraft assembly entered the receiving cone of the station, in the end it was not possible to pull it inside to create a hermetic space for the cosmonauts’ safe onto the space station. In order not to risk the lives of the cosmonauts or the safety of the orbital station itself, the flight control center decided to issue a command for automatic disconnection. However, this failed to happen, and the station continued its movement in orbit, not letting go of Soyuz-10.

One of the options for emergency undocking consisted of using a system of pyro cartridges that would cut the docking cord and free the Soyuz-10 crew, but this would have made further operation of the Salyut-1 impossible due to blocking of the airlock. A group of engineers who participated in the construction were urgently tasked with solving the emergency situation docking node of the station. On the radio, they gave the Soyuz-10 crew precise instructions for assembling an alternative electrical circuit disconnection just in orbit.

After 5.5 hours of flight while connected that nearly killed both the station and the astronauts, the squeeze maneuver was finally successfully completed. The Soyuz-10 crew returned to Earth, providing the next shift of cosmonauts with the opportunity to still get aboard the station during a future mission. Unfortunately, this extreme event was only the first omen of the tragic fate that would later befall the orbital station.

Soviet “Solaris:” The tragic story of the last crew of the Salyut-1

The next crew that went to the orbital station on the Soyuz-11 spacecraft included a Ukrainian cosmonaut. The commander of the ship was Odesan Heorhiy Tymofiyovych Dobrovolskyi, who in 1963 was appointed to the second detachment of cosmonauts (Air Force Group No. 2), after which he underwent training as part of the Soviet lunar program. Along with Heorhiy Dobrovolskyi, the Soyuz-11 crew included Russian flight engineer Vladyslav Volkov and Viktor Patsayev from Kazakhstan.

It is important to note that the Soyuz-11 crew had been prepared as a reserve. Initially, a crew led by Alexey Leonov was supposed to fly to the station, but the team was suspended from the flight due to the unsatisfactory health of flight engineer Valery Kubasov (the third crew member was Petro Kolodin).

The Soyuz-11 launch took place on June 6, 1971, and on June 7 at 10 a.m., a docking maneuver with the orbital station was successfully performed. After boarding the station, the cosmonauts noticed heavy smoke inside, which could not be eliminated due to a malfunction in the station’s ventilation system. During the first day of their stay on Salyut-1, the crew carried out emergency repairs to the ventilation system, after which they returned to Soyuz-11, waiting for the day until the air inside the station cleared for safe operation of the orbital station.

Finally, the cosmonauts transferred back to Salyut-1 and began a three-week shift, during which they performed a number of planned scientific studies and technical tests. During this period, another fire occurred at the orbital station, but it was quickly localized and extinguished thanks to the coordinated actions of the crew. It became obvious that the rush to get Salyut-1 into orbit as soon as possible had a detrimental effect on the quality of the orbital station, as it was clearly very dangerous to be on board.

Despite a number of emergency situations, on June 29 the crew reported that all planned work had been completed, after which they received the command to prepare for the return to Earth. The separation maneuver was successful, as Soyuz-11 undocked from the station and even successfully braked, and then began a controlled descent from orbit.

Source: wikipedia.org

But in the upper layers of the atmosphere, during the separation from the main Soyuz-11 spacecraft, the launch capsule depressurized with the cosmonauts on board. Due to the dense structure and the extremely tight space inside the launch module, it was not possible for the cosmonauts to use the high-altitude spacesuits that could have saved them. Therefore, the entire crew of the Soyuz-11 was killed instantly. The Salyut-1 DOS itself, after spending about 180 days in orbit, was remotely de-orbited on October 11, 1971 and entered the Earth’s atmosphere, where it was finally destroyed. Its wreckage fell into the waters of the Pacific Ocean, forever burying with it the material memory of its existence.

The history of the Salyut-1 was full of great engineering ideas which were unfortunately rendered moot by carelessness and haste due to the space race between the US and the USSR. In the pursuit of primacy, the Soviets sacrificed safety, which resulted in the death of their talented cosmonauts.

As for the Almaz orbital station developed by Volodymyr Chelomey, OKB-52 continued its work, and on April 3, 1973, it went into orbit under the name Salyut-2. However, less than two weeks later, on April 15, 1973, a depressurization was detected inside the station, and communication with it was completely lost a day later. No longer controlled by anyone from Earth, the station de-orbited in late May 1973 and disintegrated during re-entry. Its wreckage, as in the case of DOS-1, was hidden by the waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Over the next few years, two more Almaz project space stations were launched into orbit – the Salyut-3 and Salyut-5. But in the future, the USSR would abandon the use of manned orbital military stations, concluding that their maintenance was significantly more expensive than the use of automated satellites, which were capable of performing the same amount of tasks with much less risk, primarily to cosmonauts themselves.