Space exploration would never have gone so far if mankind had confined its approach to astronomy exclusively to observation from Earth. Gazing into the starry sky, the first astronomers of Arabia and Greece began the process of understanding the universe through discussing and theorizing several millennia ago.

However, the 20th century gave humanity a unique opportunity not only to contemplate space, but also have a physical presence there. Theory finally gave way to empirical knowledge. Starting with putting small experimental satellites into orbit, in just a few years mankind dared to send human experimenters with them. This duty was taken on by the aces of fighter jet aviation, whose experience was ideally suited for performing tasks in space.

Today, we will talk about Ukrainian cosmonauts who were part of the selection group for the first manned space mission in human history. The paths of their lives are very different: tragic, ironic, full of greatness. Some of their exploits have forever entered the history of world cosmonautics, while others became part of the space heritage of Ukraine.

This is a story about five prominent Ukrainians from the first detachment of Soviet cosmonauts.

Ukrainian core of the programs “Vostok”

For many years before Yuri Gagarin became the first to reach orbit, hundreds of young pilots from all over the USSR had dreamed of touching the heavens. The 1950s were also full of dreams about space. Ultimately, under extreme secrecy, the USSR began selecting its best pilots to form a cosmonaut squadron in the late 1950s.

During this selection, 3,461 personal files of the best fighter pilots from the USSR, Poland, and East Germany were carefully studied. The commission chose 12 outstanding graduates of aviation schools, to which eight more were added a little later.

At the previous interviews, the young men were not told that the matter would directly relate to space research, with authorities instead assuring them that they would participate in tests of the latest Soviet technology. There was some truth in these words. All the cards laid on the table when the pilots were designated as astronaut trainees at the newly formed Cosmonaut Training Center of the Soviet Air Force. In order not to attract too much attention, the unit was called Air Force Group No. 1. At the end of April 1960, it was finally formed with 20 cosmonauts.

One of the cadets was Senior Lieutenant Valentyn Bondarenko from Kharkiv, an experienced Pilot 3rd class with the rank. At the time of selection, Valentyn was 24 years old.

Photo: wikipedia.org

Bondarenko was not the only Ukrainian cosmonaut in the detachment. He served alongside Crimea’s Hryhoriy Nelyubov, Luhansk native Heorhiy Shonin, Bila Tserkva’s (Kyiv Oblast) Pavlo Popovych.

The honor of commanding the detachment was given to Zhytomyran Serhiy Pavlovych Korolyov, the ideological father of the Soviet rocket and space program, which he led from 1958, working in Department No. 9 of his design bureau. He was already responsible for putting the first satellite, and now his main goal was to put a human in space. The team of cosmonauts would meet him only on June 18, 1960, when Korolyov personally presented the Vostok spacecraft to them for the first time.

Cosmonaut Bondarenko’s tragic mistake

The cosmonauts’ training began in the spring of 1960 and consisted of many stages, which included both theoretical knowledge and physical testing to establish the limit of the capabilities of each potential participant in future space flights.

Exhausting tests with simulated space conditions became routine. During one of these tests in March 1961, Valentyn Bondarenko had to live for 10 days in a pressurized isolation chamber (known as SBK-48), with the closest imitation of the conditions inside a spacecraft. The experiment was successful for Valentyn and was coming to an end.

Photo: Yuri Gagarin Museum

Before leaving the chamber, Bondarenko first had to remove the sensors monitoring his condition, which were kept on his body throughout the experiment. He removed the adhesives from his skin by wiping it with cotton soaked in alcohol.

But it was then that he made a fatal misstep. Valentyn tossed the used piece of cotton wool into the garbage container installed next to the electric stove, on which he had recently cooked his food. Unfortunately, the wool fell on the still-hot coil of the electric stove. With the air consisting of pure oxygen, the fire instantly engulfed the chamber.

Bondarenko’s quick rescue was prevented by an artificial pressure drop inside SBK-48. When the pressure was equalized and the cell door was finally opened, Valentyn was still breathing. Doctors fought for his life for several hours, but the next day, March 23, Valentyn Bondarenko died. It happened 20 days before Yuri Gagarin’s flight into space.

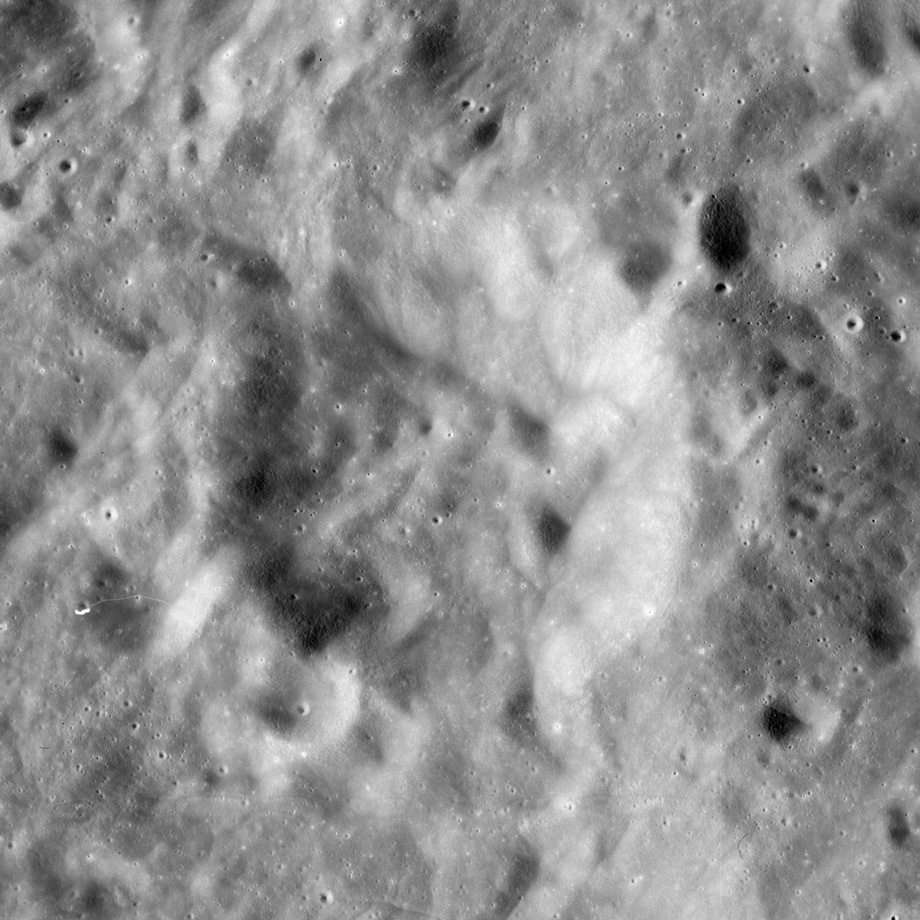

The Ukrainian cosmonaut was the first sacrifice that humanity paid for its aspirations to reach space. And although a tragic accident cut short his life, depriving him of the opportunity to reach orbit, he still ended up on the Moon, as a crater on its far side was named in Bondarenko’s honor.

Photo: NASA

Despite the tragic fate, cosmonaut Bondarenko did get to the place he always dreamed of being.

Nelyubov’s big mistake

Shortly before the first launch of the Vostok-1 spacecraft, Yuri Gagarin was chosen as the mission’s pilot. The first alternate was the Russian German Titov, and the second was the Crimean Hryhoriy Nelyubov.

Hryhoriy Nelyubov was born on March 31, 1934 in the Crimean village of Porfiryivka. He developed an interest in space from an early age.

Photo from the book Half a Step to the Start

Despite being from Crimea, Hryhoriy spent the lion’s share of his childhood in Zaporizhzhia, where he studied at Comprehensive School No. 50. At the end of 9th grade, he enrolled in the school’s aero club, and became interested in astronomy.

After graduating from his school’s flying club, Hryhoriy Nelyubov already had 50 flight hours on the Soviet Yak-4 aircraft. He then served as a naval aviator for several years, where his exceptional flying abilities caught the eye of his commanders. Soon, their reports would play a decisive role in the selection of Nelyubov’s candidacy to be one of the first cosmonauts.

He was a real favorite of the Space Training Center and also had a very warm relationship with Titov and Gagarin, as their whole families became friends. It is not surprising that this trio of friends was ultimately selected for the flight on Vostok-1, and later, after this successful mission, cosmonaut Nelyubov was under consideration to be the pilot for the Vostok 2, 3, and 4 spacecraft. However, Nelyubov would unfortunately never get his chance to reach the stars.

On March 27, 1963, Hryhoriy Nelyubov and two fellow cosmonauts, Ivan Anikeev and Valentyn Filatyev, started a fight with military police officers at a railway station. The cosmonauts were on leave and decided to visit a cafeteria, where they decided to enjoy some champagne in anticipation of Nelyubov’s birthday. The men decided to arm wrestle, and accidentally broke one of the cafeteria’s dishes. The woman working there was angered and decided to summon the military police. After an argument that turned into a fight, the officers detained the three cosmonauts and took them to the commandant’s office. At first, Nelyubov was only held as a witness, but due to his fiery character (and perhaps due to the alcohol), he began cursing at the commandant on duty, which garnered attention to the whole affair.

The blame for the incident was placed entirely on the cosmonauts. Nelyubov’s fate was uncertain at first, as he was the least involved in the incident of the trio. His comrades tried their best to shield one of the best members of their squad from punishment, but Nelyubov himself flatly refused to admit his guilt, which ultimately affected the decision of the disciplinary commission. All three participants in the incident were suspended from further participation in the space program and expelled from the squadron. For Nelyubov, this meant his career was ruined.

Hryhoriy was never reinstated in the cosmonaut squadron, and because certain officials refused to forgive his misdeeds, he was not even able to continue his career as a test pilot of new types of jet aircraft. A ridiculous domestic scandal put an end to a promising cosmonautics career.

The maneuverable duo: the story of Shonin and Popovych

The stories of two more Ukrainians from the first cosmonaut squadron, Heorhiy Shonin and Pavlo Popovych, turned out far better. Shonin, from the village of Rovenka in Luhansk Oblast, was one of the first to be enrolled in the cosmonaut squad on March 7, 1960, and waited for his space journey for nine long years.

He conquered orbit as the commander of the Soyuz-6 spacecraft during the world’s first simultaneous piloting of three spacecraft at once. Together with Shonin’s Soyuz-6, Soyuz-7 and Soyuz-8 participated in the orbital maneuvers.

The Soyuz-6 flight lasted almost five days (October 11-16, 1969). The Soyuz crews practiced space coordination, conducted an experiment on tracking the launch of ballistic missiles with help of the “Fakel” system, and for the first time in human history, performed a series of welding operations during a spacewalk with the Vulcan system. After his return to Earth, Heorhiy Shonin was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for his skill and bravery.

Photo: wikimedia.org

It was the first and only space flight in the career of the Ukrainian cosmonaut. His achievements brought him popularity and contributed to his further promotion in the service, which Heorhiy Shonin completed in 1990 with the rank of lieutenant general of aviation.

Pavlo Popovych, from the village of Uzyn near the Kyiv Oblast city of Bila Tserkva) first reached orbit seven years before Shonin. Between August 12 and 15, 1962, he participated in the first ever manned flight with two spacecraft: the Vostok-3 (piloted by cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolaev and Vostok-4 (piloted by Popovych).

Photo: NASA

During the three-day mission, Popovych and Nikolaev’s ships were able to establish stable radio communication with each other while in motion, conducted a number of physical and biological experiments, and even practiced ф maneuver of destroying enemy satellites with the help of a controlled battering ram with their own spaceships.

Shortly after the launch, Pavlo Popovych fulfilled the personal wish of the founder of Soviet cosmonautics, Serhiy Korolyov, who asked Pavlovych to sing one of his favorite songs in the spaceship. It was the first song ever sung in orbit, and it was in the Ukrainian language.

After returning to Earth, Popovych was awarded the title of Hero of the USSR. He made his next flight 12 years later – from July 3 to 19, 1974, piloting the Soyuz-14 spacecraft. During its mission, it docked with the Soviet Salyut-3 orbital station, where the crew of Soyuz-14 went to conduct scientific research on the Earth’s surface and atmospheric phenomena. For this mission, Pavlo was awarded the title of Hero of the USSR for the second time.

The leader: Serhiy Korolyov

Serhiy Korolyov was a major factor in the success of the Soviet rocket and space program and provided the first cosmonauts with the vehicles on which they would reach the stars.

However, Korolyov also experienced the political persecution by the Bolsheviks: at the end of June 1938, he was arrested for belonging to “…a pernicious Trotskyist organization that operated in Scientific Research Institute No. 3 (NKB USSR).” For this supposed crime, the man who would build the Soviet space program was sentenced to 10 years of correctional labor in a concentration camp. Joseph Stalin’s political paranoia, which led to the terrible repressions of 1937-1938, almost cost the life and health of one of the most talented rocket designers of that era.

Fortunately, Korolyov’s reputation and his personal appeal to Stalin (he wrote to the dictator several times) worked. Thus, in September 1940, Korolyov was initially transferred to an analogue of house arrest, being assigned to carry out forced labor for the development of the Soviet Tu-2 aircraft, which he did together with Andriy Tupolev during World War II.

While still in prison, Korolyov pondered the first concepts of space vehicles based on jet propulsion. He worked with Yuriy Kondratyuk to determine the optimal trajectory of travel to the Moon. It is rumored that the work of Korolyov and Kondratyuk was later used by NASA in planning the orbital trajectory of the Apollo 11 spacecraft.

Photo: vostok1.space

In 1944, all charges against Serhiy Korolyov were finally dropped, after which his life began to gradually improve. In the cosmonaut squadron, he enjoyed great authority. He personally promised that each member of the squad would fly into space, and for his part, he did everything possible to fulfill the promise.

In 1957, Serhiy Korolyov’s team launched the first satellite, putting into practice Vernadsky’s concept of multi-stage rockets. This was followed by a number of successful launches of Vostok spacecraft, as well as the launch of the multi-seater Voskhod spacecraft into orbit. During the Voskhod-2 mission, the first human spacewalk in history took place (made by cosmonaut Alexei Leonov).

It was during Korolyov’s lifetime that work began on the construction of an entire complex of Soviet space technology. Under his leadership, the first space vehicles of the Luna, Venera, Mars, and Zond series, some satellites of the Cosmos series, as well as the Soyuz spacecraft project, were created.

The success of the USSR’s space program surely did not rest solely on the shoulders of Ukrainians. It was the combined work of many other peoples united by a common dream. But without the contribution of our compatriots, it would never have become a reality.