The scientific revolution that took place towards the end of the 17th century transformed the world. The technologies which resulted from it helped to partially automate processes that previously required full human participation. The successful combination of water and fire led to the creation of steam engines, and an understanding of the basic principles of barometric pressure led to the ability to make the first voyages under water.

The Birth of the Submarine

The first idea for submersible vessels came from William Bourne. A former naval artilleryman in the British Royal Navy, he studied mathematics after his service and developed a blueprint for a hermetically sealed wooden submarine that was covered with waterproof leather. It was assumed that the boat would have to be lowered beneath the water with the help of a special vice, which then had to squeeze the boat, reducing its volume and releasing the air trapped inside, thereby allowing the apparatus to not float.

source: live.staticflickr.com

William Bourne’s submarine would remain a mere vision, as he was never able to create an experimental prototype. Nevertheless, the basic principles necessary for the implementation of underwater navigation were formulated, and it only remained to wait for a new enthusiast to undertake to bring them to life.

The first practical example of a submarine was built in 1620. It was built by Dutch physician Cornelius van Drebbel, who was living in England at that time. Structurally, his boat was similar to William Bourne’s design: the apparatus was also a sealed rowing boat which was covered with oiled leather. Inside the boat there was room for several rowers, and air was supplied to the cabin using air tubes that were supposed to remain above the surface of the water after the submarine submerged.

A prototype of the submarine successfully completed sailing trials, in which it was able to dive underwater to a depth of 12-15 feet (3.6 – 4.5 meters) and remain submerged for 3 hours. The Dutch designer was even able to demonstrate his invention to King James I. Despite successful trials and the vessel’s well-developed stern, the English king and Royal Navy officers were not delighted with van Drebbel’s invention. At that time it was difficult to come up with a practical application for such submarines, and while the vessel may have performed well sailing beneath the Thames, it would still be several centuries before the submarine could be properly realized as a weapon of war.

The first submarine design to use a ballast tank, a device that could fill with water (to sink the boat) and then release water under pressure (to float), was invented by the Italian Giovanni Borelli. The ballast tanks were giant bags made of oiled goat skin which were built into the vessel’s hull. With the help of a swivel rod, water was forced out of the skins to lighten the weight of the boat, helping it to surface. Borelli’s drawing was only presented to the world 69 years after its actual creation in 1749, when a short article describing the design of the boat was published in a journal called Gentleman’s Magazine. Like William Bourne’s submarine, Giovanni Borelli’s submersible was never built or put into service.

The history of the first submarines shows how difficult the path was for early inventors, whose unique machines were many centuries ahead of their time. The lack of practical use for submarines caused a lack of demand for diving technology, which put a halt to the development of submersibles until the end of the 19th century, when submarines began to be equipped with the first gasoline (American Holland VII, 1895), and subsequently diesel engines (French Aigette, 1904).

Steam Power: Steam Turbines and Pumps

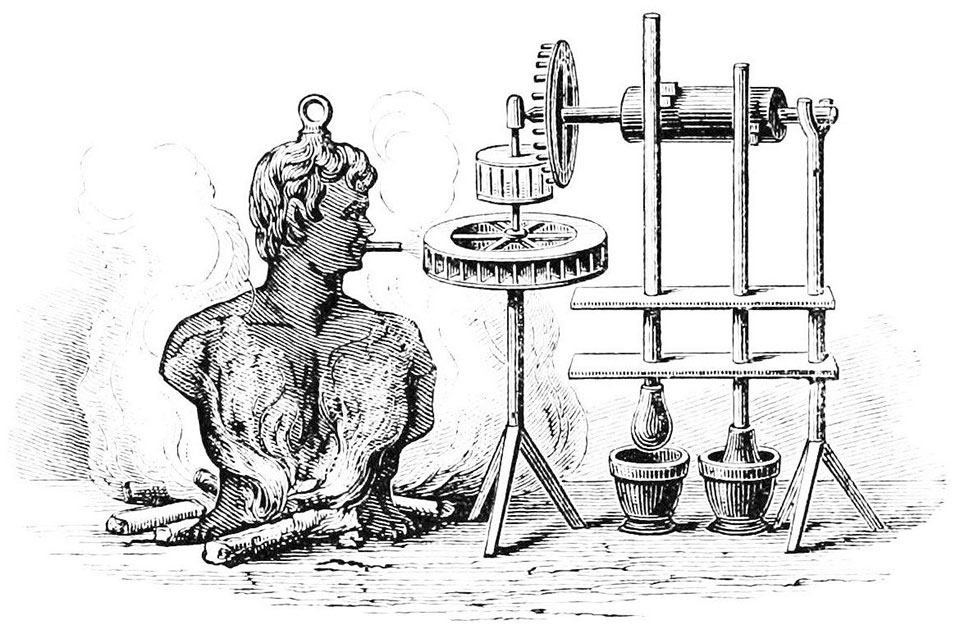

Although crude steam engine technology was most likely known to the ancient Greeks, modern technological innovators improved it significantly. The creation of the first steam turbine is attributed to the Italian Giovanni Branca. His book La Machine, which was first published in 1629, contained a concept prototype steam engine – a steam turbine, which, driven by steam from boiling water, was capable of driving a horizontally fixed wheel equipped with flat blades. Using a gear mechanism, the wheel caused the rotation of a rotary shaft, which itself drove two mortar-like pistons up and down to grind material in pestles.

source: wikimedia.org

69 years later, in 1698, British-born Thomas Savery used a similar design to patent his own steam engine, which he called “”a new invention for raising of water and occasioning motion to all sorts of mill work by the impellent force of fire, which will be of great use and advantage for draining mines, serving towns with water, and for the working of all sorts of mills where they have not the benefit of water nor constant winds.” Four years later, in 1702, he made a presentation to the Royal Society of London of his steam pump for pumping water. According to the minutes of his speech,

“Mr. Savery entertained the Society by showing his machine that raises water with the power of fire. He was thanked for demonstrating the experiment, which, as expected, was a success and was approved.”

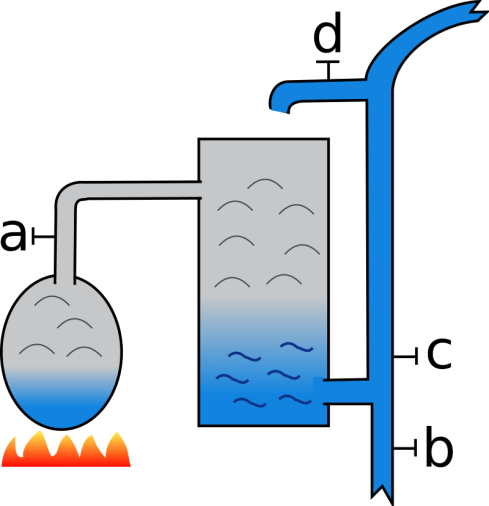

Thomas Savery’s steam pump was not an engine in the full sense of the word, as it had no piston elements, and the pumping of water was accomplished by means of the vacuum created in the cylinder.

source: wikimedia.org

In 1702, the machine went into production and hit the market. The main customers for the invention were British miners, who came up with the idea of using the Savery pump to clear water from mines.

However, the pump struggled to meet expectations for its performance in the unforgiving environment of underground mines: in some areas, the flow of groundwater was so strong that the boiler simply didn’t have the capacity pump out water fast enough, which resulted in the cost of maintaining drainage pumps significantly exceeding the money earned from coal mining. Savery’s steam engine was prone to exploding and, when placed at a sufficient depth, threatened to block off the entire mine shaft in the event of an explosion. Placing the pump deep within mines also risked partial or complete flooding of the boiler, which would require the procurement of a second pump in order to rescue the first, which was extremely unprofitable.

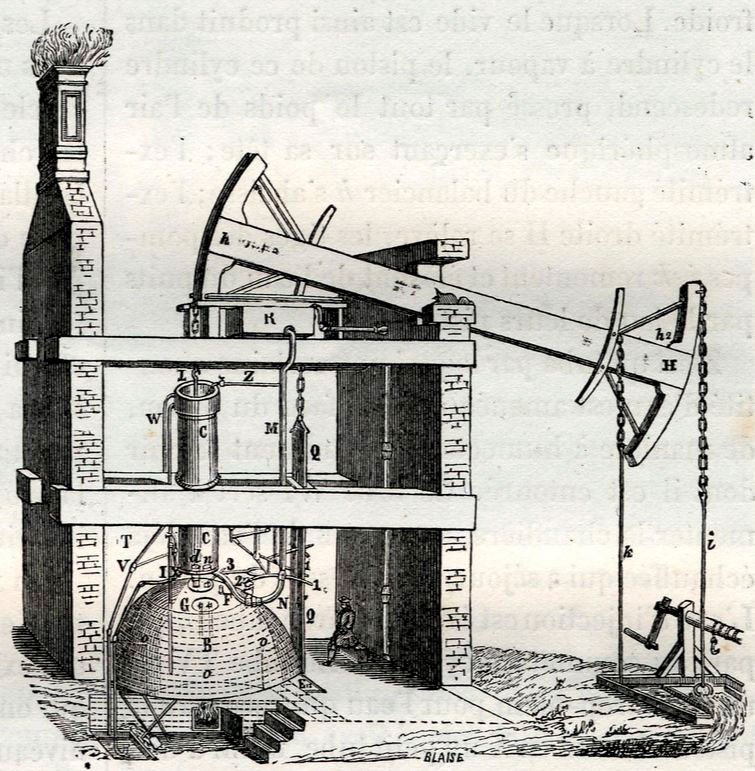

It was clear to Savery that the power of the steam that pumped out the water alone was insufficient. He decides to partner with a local middle-class blacksmith, Thomas Newcomen, who, together with his partner John Colley (whose name would also go on the patent for the new device), re-designed the Savery pump to increase its power by connecting atmospheric pressure and piston mechanism.

Newcomen’s atmospheric steam engine had a metal cylinder into which piping-hot steam from the boiler. The steam cylinder was cooled with cold water through a water pipe valve, resulting in a pressure drop that created a vacuum inside the cylinder. The suction force of this vacuum drove the piston, which was responsible for the operation of the pump. The first versions of Newcomen’s atmospheric steam pump were capable of producing up to 6-8 full piston strokes per minute. Subsequently, Newcomen would refine some elements of his condenser cylinder, thereby bringing this figure up to 10-12 cycles per minute.

source: www.historycrunch.com

Newcomen’s atmospheric engine would become the prototype of James Watt’s steam engine, a design that would explode in popularity as the central steam engine of the industrial revolution.

The fruitful partnership of the two Thomases from England, Savery and Newcomen, is an excellent example of the business relations which emerged throughout Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was these partnerships which in the distant future would lead to the total and widespread commercialization of production, and would give the necessary impetus for their subsequent automation and modernization.

The delineation of the “Modern Era” is somewhat misleading, since not all peoples entered this era at the same time. Nevertheless, one thing remains obvious: the arrival of the Modern Era completely transformed and transformed human civilization, making it Eurocentric and spreading new standards of scientific activity, economics, philosophy and culture throughout the Earth. It is the scientific revolution, supported by the evidence-based empiricism of the Modern Era, that will bring humanity close to another revolution, the industrial one, which we will talk about in the next part of our cycle dedicated to the history of the development of science and technology.