In the first article of our series on the creation of the Outer Space Treaty (OST) and the legal regulation of activities in space, we talked about how the world’s leading powers worked to make outer space into an armed conflict-free zone. The initiative, built up through negotiations and UN resolutions over the course of several decades, was able to guarantee the peaceful development of orbit for many decades, and countries have by and large played by the rules.

However, the issue of conducting commercial space missions has remained unresolved. Out of concern that commercial activity in space could create the conditions for the potential interstate conflicts over space resources, the original text of the OST ignored the very possibility of private space activity.

Humanity has by and large managed to live and develop according to the laws of the market when it comes to space activity, and it was only a matter of time until technological progress allowed commercial activities to reach orbit. By the end of the millennium, competition was clearly needed throughout the space sector.

Laying the ground for commercial space launches

The text of the OST did not offer any consideration for the possibility of the private sector independently carrying out space launches. This policy was mainly lobbied for by the Soviet Union, while the United States steadily insisted on the integration of free market mechanisms into the process of space exploration. The decision turned out to be a compromise: commercial companies were allowed to participate in space missions, but their activities were completely subordinated to state bodies.

Countries began to establish their own space agencies, which would be able to bring together research institutes and industry to create a sustainable space sector.

At the time of the signing of OST, only the United States (NASA, founded in 1958), the USSR (Ministry of General Machine Building, established in 1955), Spain (INTA, 1942), and France (CNES, 1961) had their own space agencies or research institutes. The UN also launched its own Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA, 1958). Not until 1975 would Europe establish its own space agency, the ESA, which brought together the industrial and scientific potential of 22 European countries to conquer orbit.

There is no doubt that the cooperation of the space agencies around the world has had a beneficial effect on the development of the entire space industry, but the pace of this progress was extremely slow. The preparation of single space missions stretched out for years, which meant that the contractors responsible for the creation of rocket technology and equipment did not see the need to develop consistent, large-scale production capacities.

As the world’s leading commercial power,, the United States decided to be the first to start writing in the rules of this game. In 1962 (five years before the OST appeared), US President John F. Kennedy signed the Communications Satellite Act, which allowed private satellite companies to join forces to make satellite telecommunications a more accessible and profitable business.

US antitrust authorities had serious objections to the initiative, so in order for the law to be agreed upon, its authors adopted a compromise solution: private companies were allowed to merge, but all their activities had to be regulated by a number of government bodies like NASA, the Federal Communications Commission,) and directly by the President.

The Communications Satellites Act was the first example in the history of American law where private companies were involved in the process of creating space technologies, and they were given a lot of freedom of action.

Turning point 1984: Big Brother allows commercial launches

The Cold War and the space race between the US and the USSR steadily pushed the industry forward, and US lawmakers increasingly began to realize the need for private aerospace companies to have direct access to the space sector. In 1984, during the 98th Congress, the Commercial Space Launch Act (known as HR 3942) was adopted.

The legislation recognized the right of commercial aerospace companies to develop their own artificial satellites, launch vehicles, and infrastructure to launch them into space. The US Secretary of Transportation was ordered to coordinate the activities of commercial companies and exercise government oversight. After clearing Congress, the law went to the desk of President Ronald Reagan, who signed it on October 30, 1984.

Photo taken November 13, 1984, exactly two weeks after Reagan signed the Commercial Space Launch Act

Source: NASA

The Act gave private companies their first real chance to conquer orbit. All they had to do was obtain a license for space launch from the Secretary of Transportation. Although government officials still had the legal right to fully regulate the activities of licensees, and the secretary was empowered to unilaterally revoke issued launch licenses, this law undoubtedly gave a massive boost to the space launch industry in the United States.

This became especially evident at the turn of the millennium, when in 2004, during the presidency of George W. Bush, a number of amendments were made to the Commercial Space Launch Act, the most important of which allowed the commercial sector to conduct manned space missions. The amendments also introduced a “learning period” – a temporary ban on intervention by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the regulation of the activities of private space companies (in November 1995, control of the Commercial Space Transportation Administration was transferred to the FAA).

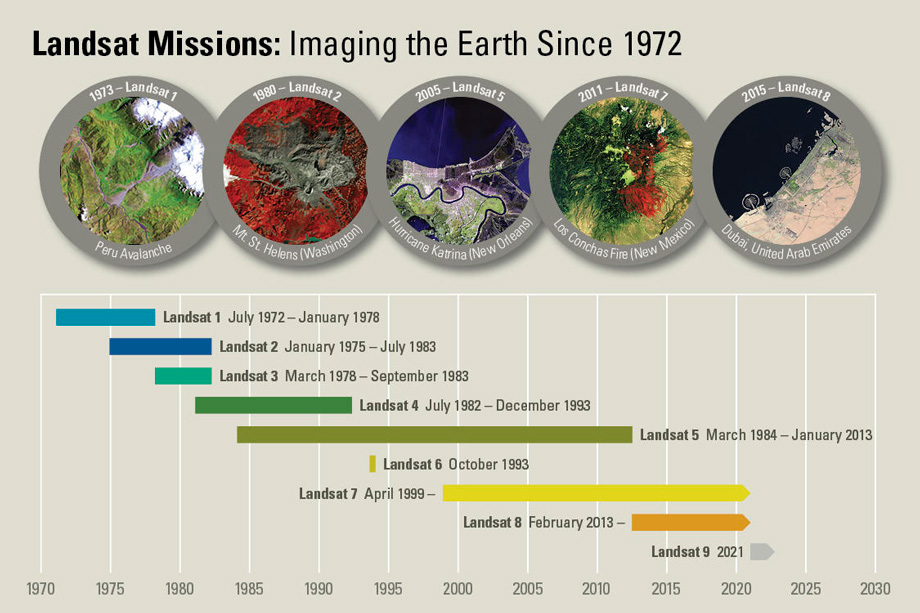

Also in 1984, the Land Remote Sensing Commercialization Act was passed, transferring the government’s Landsat satellite program, which had been in operation since 1972, to private ownership. The law allowed private satellite monitoring companies to conduct remote Earth observation and helped the industry grow in the future by attracting third-party investment and private capital to the process, thus easing the burden on the US federal budget.

Thanks to the advent and further modernization of the Land Remote Sensing Commercialization Act, by 2010, 31% of the total number of space launches in the United States were from the private sector. This was an obvious triumph for the American legal framework, and it led to the emergence and further development of such giant companies as SpaceX, Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic, and others.

In turn, the Land Remote Sensing Commercialization Act gave a tangible impetus to the development of the remote sensing market, which today participates in programs to monitor weather, fight climate change, protect the environment, inform civil engineering, and even support precision agriculture from orbit.

The Space Laws of 1984 would serve as the catalyst that would rocket the US into being by far the world’s leading space power. But in the mid-2010s, the Americans made an even bolder attempt to commercialize space.

Green light for the extraction of extraterrestrial resources

The OST defined near-Earth and space resources as the property of human civilization and all countries of the world, regardless of their economic development. And although American laws allowed private space companies to launch rockets and build spacecraft, they did not in any way address the issue of extracting the solar system’s riches.

Then the situation suddenly changed. On November 25, 2015, US President Barack Obama signed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act into law, giving commercial aerospace companies the right to extract and use for their own purposes any fossil resources and minerals that they can extract with their own efforts on planets, satellites, asteroids, or other areas of space.

The Act untied the hands of private market players in the cosmic mining of gold, platinum, iridium, tungsten, silver, osmium, and other non-ferrous metals. The law also allowed for the processing and in-place use of mined aluminum, iron, titanium, cobalt, and other metals as materials for the construction of planetary outposts. Extracted and purified water and oxygen could also be processed on-site and used to supply crews in long-term space or planetary missions.

Ammonia, hydrogen, and oxygen mined in orbit were also allowed to be processed for further use as rocket fuel. The creation of spacecraft fuel processing technology, combined with the production of purified oxygen and water, could solve the problem of long-term space travel and pave the way for the next generations of space explorers to organize manned missions to the most remote regions of the solar system.

The only limitation the law imposed was a ban on the appropriation and private use of organic life forms found in the process of exploring space and celestial bodies. Eric Anderson, co-founder of US asteroid mining company Planetary Resources (acquired by ConsensSys at the end of 2018), called the signing of the bill in 2015 “the biggest recognition of property rights in history.”

In 2017, two years after the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act was adopted in the US, Luxembourg became the first European country to allow commercial companies to extract and appropriate resources mined in space. In the same year, the United Arab Emirates, Portugal, and Japan entered into an agreement with Luxembourg on the joint and coordinated extraction of extraterrestrial minerals.

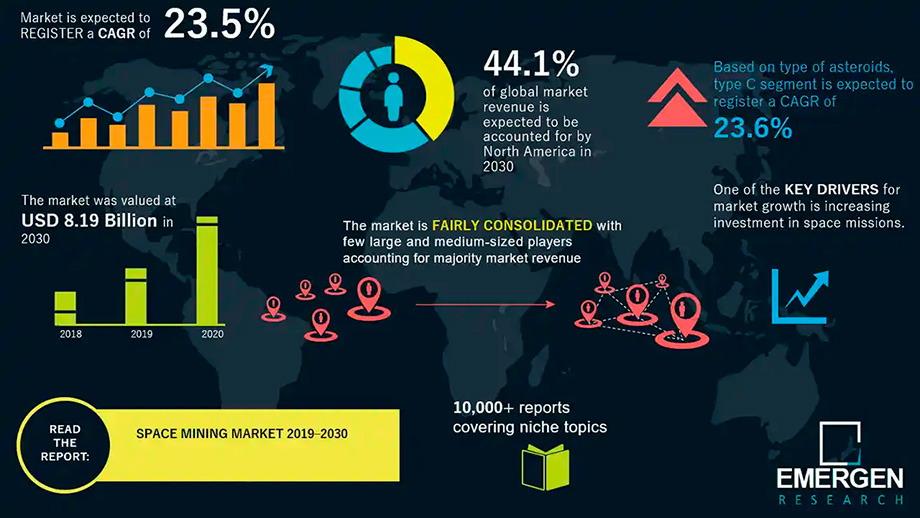

This shift has not been without pitfalls. After the US adopted its law on the extraction of extraterrestrial resources, it faced criticism from some signatories of the Outer Space Treaty and third-party scientific institutions, who saw it as a violation of the provision forbidding the nationalization of space resources. Despite arguments to the contrary, it was the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act that launched the development of a number of private initiatives for the extraction of extraterrestrial resources, which include companies such as AstroForge, Trans Astra Corporation, ispace, and Moon Express.

According to a financial forecast by Mordor Intelligence, the US space mining market in 2021 was estimated at $11.36 billion, and its average annual growth rate through 2036 will be around 13%.

The rather slow growth of the space mining market is still associated with the high costs and time required for the development and launch of space harvesters, so investors in the NewSpace industry so far remain reluctant to stake claims.

Some investors find it much more profitable to invest in solving more pressing problems in orbit, such as cleaning up space debris. Legislators are ready to meet them halfway, creating an appropriate legislative framework for the regulation of this activity, which we will discuss in the next installment of our What is allowed in Space series.