In the first installment of our series, we talked about the most famous unsuccessful lunar missions. Now let’s talk about the failures in the conquest of deep space. Most of them are connected in one way or another with Mars, although space technology has also failed on the way to other celestial bodies. But first things first.

One missing sign

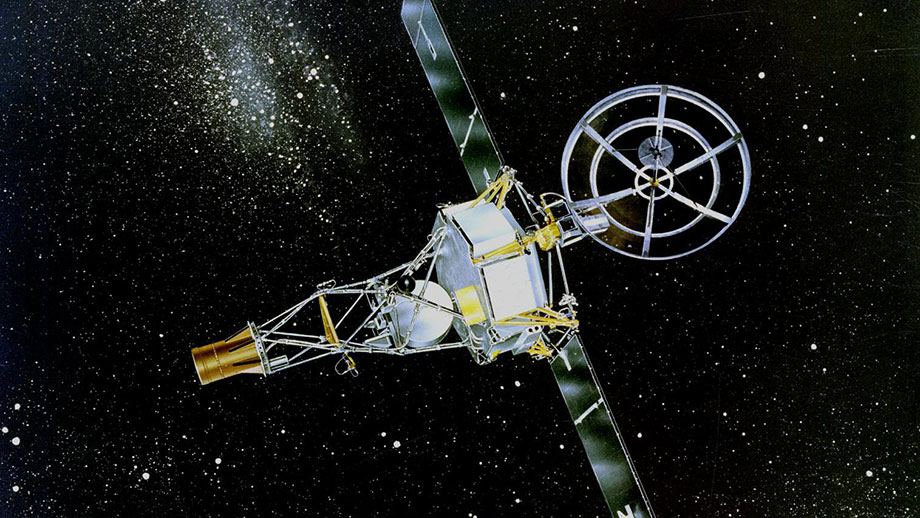

July 1962. The USA was still far behind the USSR in the space race, and was trying to turn the tide in any way it could. Particularly high hopes were pinned on Mariner 1. The spacecraft was set to fly to Venus, about which practically nothing was known at that time.

However, Mariner 1 failed to make it to Venus, it couldn’t even leave Earth’s atmosphere. During launch, a radio beacon malfunction caused the Atlas carrier rocket’s antenna to lose contact with the ground guidance system. The on-board computer took control, but this only made things worse. The Atlas rocket’s engines received a series of erroneous commands, and the rocket began to fly way off course. Finally, for security reasons, the rocket had to be scuttled in the atmosphere.

source: d2pn8kiwq2w21t.cloudfront.net

In the course of subsequent analysis, it turned out that everything happened due to a single missing character in the control program. The press dubbed it “the most expensive hyphen in history” (the cost of the lost device was $18.5 million, which, adjusted for inflation, is now equivalent to about $180 million). To be completely accurate, it wasn’t a hyphen specifically that was missing, but a line at the top of the symbol. But this was little comfort to the designers. Luckily for NASA, the identical Mariner 2 spacecraft, launched a month later, managed to complete its predecessor’s mission and reach Venus.

Aborted Mars 3 Transmission

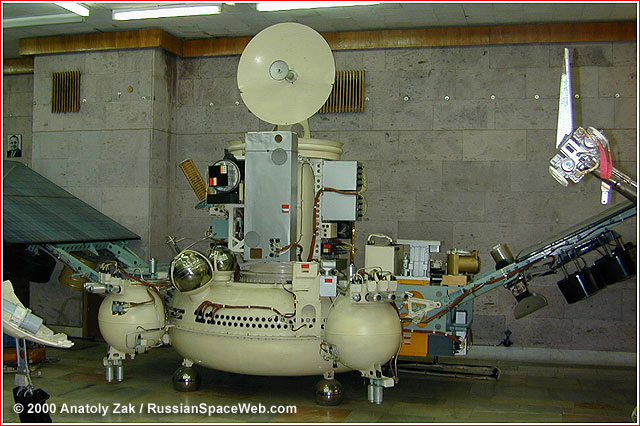

Even today, landing on Mars is considered a rather tricky enterprise. Back in the early 1970s, when our knowledge of the planet left much to be desired, and technology was much more primitive, it was far more difficult. It is all the more surprising that Soviet engineers managed to solve this problem. It is even more surprising that this, without exaggeration, outstanding success did not even bring anything to the USSR.

On December 2, 1971, the Mars 3 mission lander entered the atmosphere of the Red Planet. An extremely complex method was used for its landing, consisting of a combination of parachutes, braking engines and a system that diverts the parachute container with the spacecraft’s engine (the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers subsequently landed on Mars using the same method).

Mars 3 made a soft landing. Shortly thereafter, the apparatus began transmitting the first-ever panorama of the Martian surface. But just 14.5 seconds after the start of the communication session, Mars-3 fell silent forever. Mission control received only a chaotic set of stripes from which nothing could be discerned. What exactly happened is still unknown.

It is unlikely at that time that anyone in the USSR could have imagined that Mars-3 would stand as the high point of Soviet efforts to study the Red Planet. Subsequently, noSoviet spacecraft ever again managed to make a soft landing on Mars.

“Phobos-1” and the letter “V”

Mars became a real graveyard for Soviet space technology. None of the missions launched to the Red Planet in the 1960s and 1970s managed to complete of the tasks assigned to them. In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union made a new (and ultimately final) attempt to succeed, relying on a pair of Phobos stations that had an identical design. At that time, they were the largest vehicles ever sent into interplanetary space. “Phobos” were called upon to carry out a very ambitious program for the study of Mars, as well as to land descent vehicles on the surface of the moon of the same name.

source: www.russianspaceweb.com

However, less than two months after its launch, the mission control center lost contact with Phobos-1. Attempts to re-establish contact were unsuccessful. During the subsequent debriefing, engineers established that, as with Mariner 1, everything happened due to a missing character in the computer program responsible for controlling the device. In this case, the letter “V”.

As for “Phobos-2,” it still managed to reach the Red Planet and even complete the first stage of its scientific mission. But when the station was preparing to land descent vehicles on Phobos, mission control lost contact. Efforts to re-establish contact were unsuccessful.

Sudden death of the Mars Observer

If the USSR has always had catastrophic bad luck with Mars, then NASA, on the contrary, usually succeeded. But in 1993, the agency received an extremely painful reminder of how treacherous the Red Planet could be. Just three days before the new and very expensive Mars Observer was supposed to reach Mars, NASA lost contact.

Engineers then made a number of attempts to restore contact with the apparatus, but to no avail. The Mars Observer failed completely for reasons that remain a mystery to this day. It is assumed that the device’s engine exploded, but we will not likely ever be able to verify this.

source: wikimedia.org

The death of the Mars Observer was a serious blow to NASA’s reputation. Many engineers and designers say that cases of sudden loss of communication with spacecraft still give rise to very unpleasant “flashbacks” and fears that their mechanical offspring could share the fate of the Mars Observer.

The expected failure of Mars 96

In 1996, Russia attempted to demonstrate to the world that rumors of the imminent death of its space program were greatly exaggerated by launching the Mars 96 mission. It was a very, very ambitious project. Mars 96 was supposed to go into orbit around the Red Planet, and then drop a couple of small landing stations, as well as a number of probes, onto its surface.

At the same time, the design of Mars-96 was based on that of the Phobos stations. Of course, the developers claimed that they took into account all of their predecessors’ shortcomings. At the same time, considering the Russian space program’s chronic problems with funding and the unfortunate experience of Soviet missions to Mars, many independent experts were rather skeptical about the project’s prospects and estimated its chances of success at 50-60%.

Whether Mars 96 could have carried out its mission or not, we will never know. Due to the failure of the upper stage of its launch rocket, the device remained trapped in near-Earth orbit, and fell back to Earth after several orbits. Interestingly, the exact crash site of Mars 96 has never been established. Initially, it was reported that its surviving fragments (including those containing plutonium-238 radioisotope thermoelectric generators) fell into the Pacific Ocean. Later, evidence appeared that some fragments of the station could have reached South America. If so, they have so far not been found.

The swan song of the Japanese space program

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Japan was perceived by many in the West as the next superpower. Its economy was growing rapidly, and the country itself was actively conquering new areas, including space. These efforts culminated in the Nozomi mission, which set its sights on Mars. If successful, Japan would become the third country in history to explore the Red Planet using a spacecraft.

Nozomi was launched in July 1998. Since the power of the Japanese rocket was not enough to directly send the device to Mars, the spacecraft had to perform a gravity maneuver near the Earth for additional acceleration. However, the operation went wrong, and Nozomi went into an improper orbit.

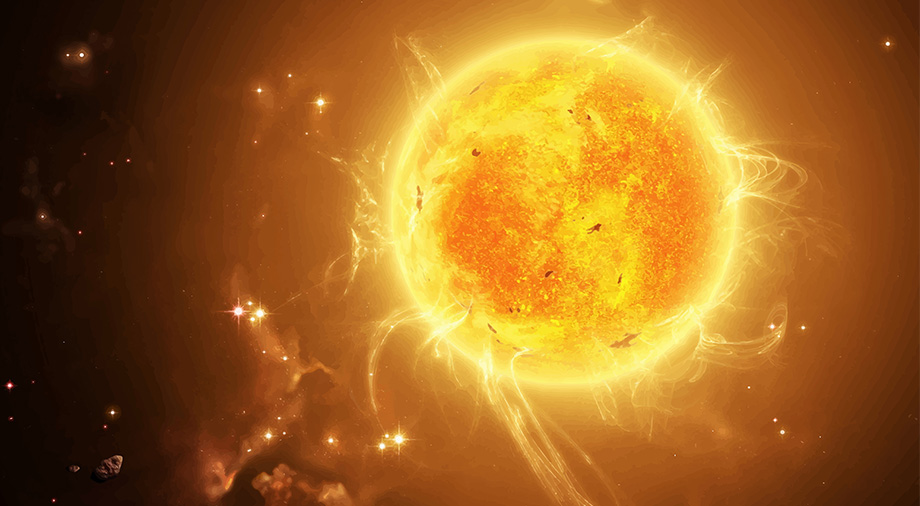

At the cost of a great expenditure of fuel, the spacecraft was nevertheless able to be directed to a new trajectory, ensuring its arrival to Mars in 2003. But during the flight, Nozomi was hit by a solar flare, which disabled its fuel heating system. By the time the probe reached Mars, the hydrazine in its propulsion system had frozen. Nozomi could not make the necessary maneuver to enter orbit and simply flew past the planet. Since then, Japan has never launched vehicles to Mars again, and the crown for the next superpower has assed to China, which has managed to achieve a number of rather impressive successes in space.

The Failed Space Odyssey of 1999

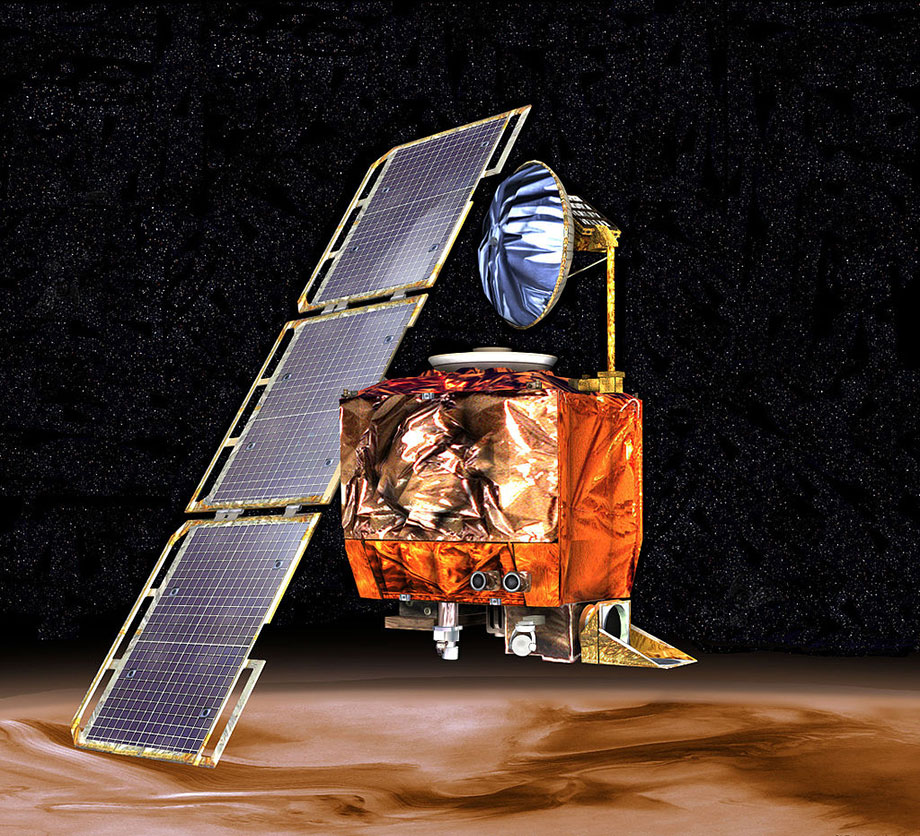

NASA was supposed to pass the year 1999 under the sign of Mars. In September, it planned to send the Mars Climate Orbiter to the Red Planet. It was supposed to do climate research, as well as serve as a repeater for the Mars Polar Lander mission, whose landing was scheduled for December of that year.

On September 23, the Climate Orbiter began a braking maneuver to enter orbit around Mars. It quickly became clear that something had gone wrong. Communication with the device was interrupted earlier than planned, and it was not possible to restore it.

source: wikimedia.org

Subsequent analysis of the data showed that the Orbiter’s flight path did not go as planned. The probe passed at a very short distance from the surface of the planet and simply burned up in its atmosphere. The cause of the error shocked experts. It turned out that it all boiled down to a discrepancy between two measurement systems. The software of the mission control center computers used imperial units (lbf), while the onboard Mars Climate Orbiter computer used newtons. Because of this contradiction, the apparatus deviated from its intended course.

A similar fate befell the Mars Polar Lander. After entering the atmosphere, the apparatus fell silent forever. According to experts, the probe was also most likely doomed by a software bug which caused it to prematurely turn off its braking engine and crash.

Failed comet voyage

The new century has been quite favorable to NASA’s interplanetary missions. Embarrassing accidents are almost a thing of the past, and even Mars has ceased to cause problems, and the periodic landings of American rovers on the Red Planet have thus become expected as a matter of course.

But still, there has been one unpleasant exception in NASA’s otherwise successful 21st Century of successful interplanetary missions: the 2002 CONTOUR mission. It was supposed to make flybys of at least three comets, but the device was fated to never reach any of them. Shortly after CONTOUR released its solid propellant engine in order to perform a planned maneuver, contact with it was lost. Later, telescopes found several objects on the spacecraft’s trajectory, which indicated it had been destroyed

As with the Mars Observer, an engine explosion was cited as the most likely cause of CONTOUR’s doom. It is unlikely that we will ever know whether this is actually the case, or whether the apparatus was destroyed by something else.

Repetition is mother of learning

In 2011, Russia again tried to demonstrate to the world that it remains a great space power and is still capable of carrying out interplanetary missions. Her goal was again Mars, or rather, its moon Phobos.

Alas, the Russian space program had not learned enough from the inglorious fiasco of Mars 96. Instead of starting over and launching some relatively simple and inexpensive probe to Mars as a test of their aptitude that could be used to test equipment and gain experience, they went right back to building a huge and extremely complex apparatus called the Phobos-Grunt. It was entrusted with an exceptionally ambitious goal – the delivery a soil sample

All this led to the repetition of the disaster of 15 years earlier. Like Mars 96, Phobos-Grunt suffered an upper stage failure, got stuck in low Earth orbit, and eventually joined Russia’s Pacific space constellation. The first Chinese probe for Mars research, Inho-1, shared the same fate.

If the failure of Mars-96 could still be attributed to the hardships of the 1990s in Russian space, then Phobos-Grunt clearly demonstrated that Russia’s struggles in space were not simply a matter of money, but a matter of the degradation of the Russian space industry. This was so clear that China and India, which had previously planned joint interplanetary missions with Russia, subsequently abandoned their plans.

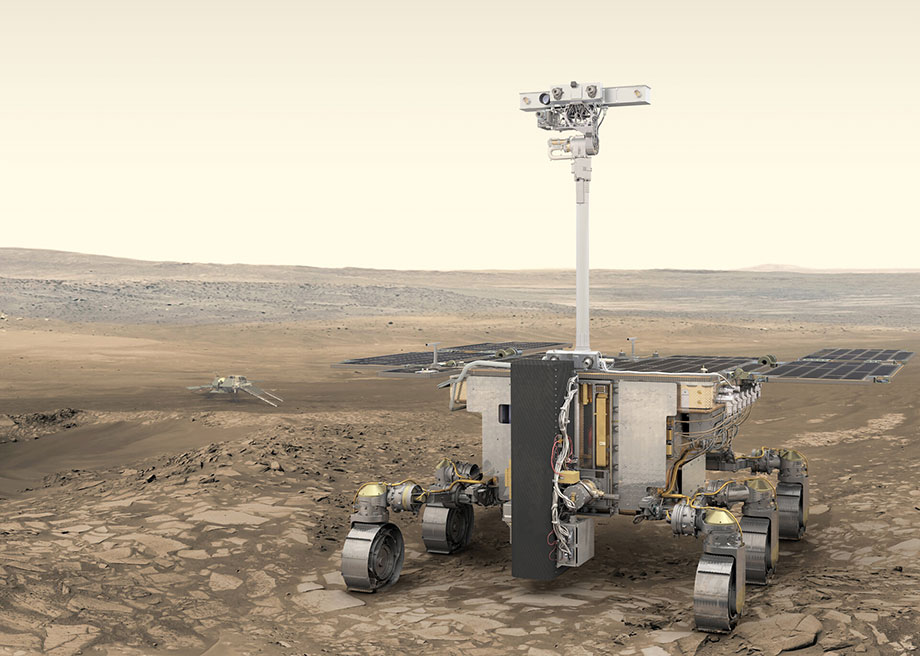

A Hard landing for the ESA

Since its inception, the European Space Agency (ESA) has made two attempts to make a soft landing on Mars. The first was the Beagle 2 probe. On February 25, 2003, the spacecraft separated from the Mars Express apparatus and began to descend to the Red Planet. ESA received regular telemetry until the moment of landing, after which the Beagle 2 fell silent and never made contact again.

The mystery of Beagle 2’s failure was answered only in 2015, when the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) device managed to find and photograph the crash site. The reason turned out to be as maddening as it was simple. During landing, one of the shock-absorbing air bags did not completely deflate, making it impossible for the probe to deploy its solar arrays.

In 2016 Schiaparelli module met the fate of Beagle 2. It was part of the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) mission, and was supposed to work out a technique for atmospheric entry and demonstrate the possibility of a soft landing on the surface of Mars. While the module successfully handled the first part of its mission, it could not handle the second. 50 seconds before landing, mission control lost the signal. A few days later, the MRO photographed the crater left at the Schiaparelli crash site. A subsequent investigation determined that due to a malfunction in the inertial measuring unit, the module incorrectly determined its altitude and fired its parachute prematurely.

source: www.esa.int

A third attempt to land a European apparatus on Mars was scheduled for February 2023. Its main star was to be the Rosalind Franklin rover, whose task was to search for the existence of traces of life on Mars. But after the start of a large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, ESA severed all ties with the aggressor country. As a result, the Rosalind Franklin lost its rocket and landing system, and for the moment remains stranded on Earth. Even according to the most optimistic estimates, the first ever European rover is now unlikely to be launched before 2026-2028.