In 2014, China allowed private capital into its space sector for the first time, enabling businesses to contribute to the commercial development of launch vehicles and satellites. Over the next 10 years, Beijing gradually reduced its state presence in the aerospace industry, allowing local entrepreneurs to set new trends in the sector. The majority of the market is still dominated by state-owned companies (particularly those under the national CAS and CASC conglomerates), but private businesses have begun to fill a necessary niche in the design of small and medium-sized rockets, as well as a range of small satellites and CubeSats.

The successful adoption of the American model of integrating private business into the aerospace sector has allowed China, if not to catch up, then at least to come very close to the military and space potential of the countries of the North Atlantic bloc in just a few years. This has caused great alarm in the West. Today, we will focus on new developments in China’s military-industrial space complex and examine what the Chinese development model has in common with the approach of its main strategic competitors.

Three Chinese satellite mega-constellations

At the end of May 2024, the satellite company Shanghai Lanjian Hongqing Technology Company (Hongqing Technology), 48% of whose shares are owned by the Chinese rocket manufacturer Landscape, submitted a request to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to deploy a constellation of 10,000 satellites. This constellation will operate in 160 different orbital planes, creating a unified network for satellite communication, navigation, and monitoring in low Earth orbit (LEO: 600 km) called Honghu-3.

Conceptually speaking, Landscape is very similar to SpaceX and it aims to build reusable launch vehicles with a payload capacity of up to 21 tons capable of deploying numerous satellite clusters into LEO (some modifications of the Falcon 9, meanwhile, have launched up to 60 Starlink satellites into orbit at once). Another similarity is its focus on vertical takeoff and landing (VTVL) technology. SpaceX was the first to widely use this technology, which significantly reduces the cost of putting payloads into orbit. Landscape aims to replicate SpaceX’s by placing its own Starlink analog into orbit.

Credit: LandSpace Technology

The Honghu-3 military satellite mega-constellation will allow the PRC to “keep an eye” on 160 orbital planes simultaneously while focusing on monitoring various areas of interest. This represents almost total coverage of the entire hemisphere of the Earth in real-time with the possibility of rapid signal retransmission, including using China’s own laser telecommunications systems.

The Honghu-3 is the third satellite mega-constellation China has announced, having been unveiled as part of Beijing’s plans to strengthen its LEO presence. In November 2023, the Chinese private satellite manufacturer Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology raised $943 million to build a mega-constellation of 12,000 so-called G60 “Starlink” satellites (one wonders if Mr. Musk receives a percentage for lending his trade name to the Chinese).

Several private companies located in Shanghai, including major firms like Shanghai Alliance Investment, have acted as the main investors of venture capital for this project. Despite the substantial amounts of non-state funding, however, it should be understood that many private companies and incubation centers involved in the funding and creation of the G60 “Starlink” system, including Guosheng Capital, Hengxu Capital, and CAS Capital, are ultimately subordinate to the state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). This means that their activities are directly managed by the country’s military-political leadership.

In the first phase of deployment, the G60 “Starlink” constellation will consist of 1,296 satellites, which will be placed into orbit in several stages via more than 36 rocket launches. After deployment in Earth’s polar orbit, each of the G60 “Starlink” satellite clusters will take its orbital position and will organize several main activities: satellite communication and navigation (in the Ku, Q, and V frequency bands), broadband signal relay, navigation, and geospatial positioning.

2024 will mark the starting point for China’s G60 “Starlink” mega-constellation. At the beginning of August 2024, China plans to launch the first 18 G60 satellites, most likely using the Long March 6A launch vehicle, which was developed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) in collaboration with the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST).

China only plans to put 108 satellites into orbit in 2024, or less than 1% of the total constellation. This relatively small figure is likely due to China’s limited access to powerful reusable liquid-fuel launch vehicles, which could significantly increase the deployment rate of subsequent G60 satellites. That said, possible solutions may emerge from Chinese startups currently competing to develop reusable VTVL rockets. The most ambitious private player showing progress in this area is Landspace, which is developing the Zhuque-3 launch vehicle, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Earlier, in 2021, China announced Guowang, its most ambitious constellation. Upon full deployment, Guowang will consist of about 13,000 satellites in low and medium Earth orbits. Together, the Guowang satellite network and the G60 “Starlink” mega-constellation are set to become the main competitors for the American Starlink constellation, which will ultimately be made up of around 42,000 satellites. Civilian broadband communication is just one of the reasons driving the development of the Chinese Starlink competitor: Russia’s war in Ukraine has highlighted another crucial mission that the system could perform if needed: providing sustainable satellite communication for the Chinese military.

Military applications are often initially tested on Shiyan military satellites. The name “Shiyan” translates as “experiment,” and the scarce information that Beijing reveals about these satellites hints that they serve as demonstration platforms for a range of military space technologies. Over the past two decades, China has launched more than 30 Shiyan series satellites into orbit. The latest, Shiyan-23, was launched on a Long March 4C rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on May 12, 2024.

Credit: Weibo @China航天

Encouraging the private sector to create satellite mega-constellations is an understandable move for Beijing: production orders for thousands of satellites attract investors and reduce the burden on China’s national aerospace sector. However, upon closer examination, it is clear that the regulatory state is not wholly divorced from this process, as it constantly provides direction to the private sector regarding what exactly it wants to receive.

Quickly adopting the American space economy model, wherein private companies are actively encouraged to engage with the American military-industrial complex (MIC), China has given the green light to dozens of private companies to contribute new concepts and technological solutions to the Chinese space market. Many of these solutions are aimed at extending the operational lifespans of Chinese satellites in orbit through the implementation of orbital servicing and refueling systems.

Orbital refueling stations and space tugs

The deployment of satellite mega-constellations will require the infrastructure necessary for their maintenance, especially orbital refueling stations (specifically for cryogenic fuel). One recent report, titled “The Logistics of PLA Satellites in Orbit,” which was published by the Chinese Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) on March 18, 2024, claims that China has already completed the development of a refueling station, which will operate in geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO). The report notes that this station can be used to refuel both civilian and military satellites.

Beijing issued a request for the development of an orbital refueling station in 2018, after which active work began. As of today, PLA technicians are being trained to control the orbital station from ground-based flight control centers. The Chinese government has also reached out to commercial aerospace enterprises to encourage their participation in developing this nascent technology. Successful demonstration and subsequent large-scale deployment of orbital refueling stations will significantly enhance the resilience of China’s satellite constellation, greatly extending the operational lifespan of its satellites in orbit.

Among other space capabilities that China seeks to develop are space tugs for deorbiting satellites. In 2021-2022, China confirmed the existence of such a tug, named Shijian-21, which was developed by SAST. After being placed into orbit, Shijian-21 approached the defunct Beidou-2 G2 navigation satellite, performed a docking maneuver, and, using its maneuvering thrusters, transferred the “dead” satellite into a more distant “graveyard” orbit.

It should be noted that this space tug technology can also be used for military purposes, namely for approaching and intercepting enemy combat satellites. In recent years, various analytical and intelligence agencies have published reports indicating that both Russia and China have been developing these kinds of satellite weapons, which can selectively counter critical American and allied satellites.

Despite Beijing officially labeling the American Starlink system as a threat to its national security, however, Musk’s satellites are unlikely to be targeted, since the Starlink constellation is too large for such “space boarding” tactics to be effective. That being said, other U.S. military satellites, such as large, solitary spy satellites and SATCOM relays that operate in geosynchronous Earth orbit, could indeed be priority targets for Chinese interceptor satellites.

Spaceships: Shenlong’s third flight

Another domain of space technology that China has been trying to gain ground over recent years is spacecraft, both manned and unmanned.

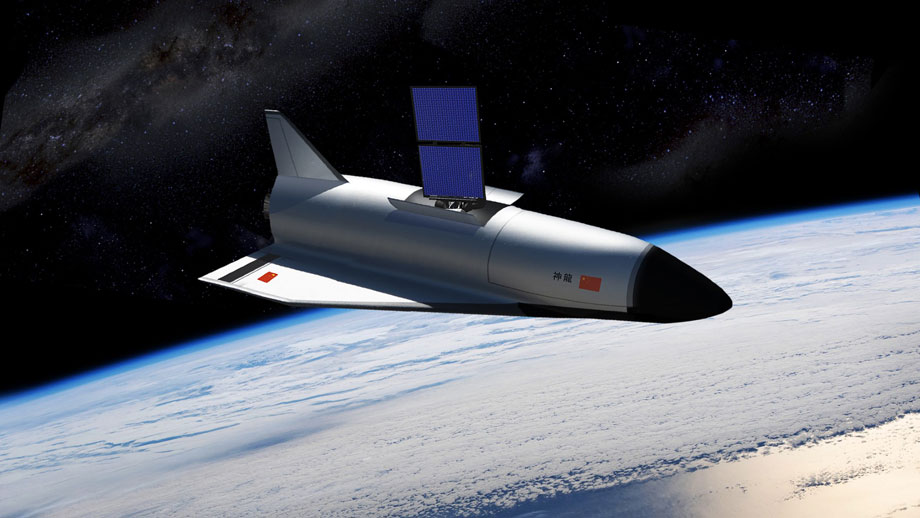

One of the latest developments in this area was the launch of the Shenlong reusable spacecraft (currently in an unmanned version), which China placed into orbit aboard a Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan launch center on December 14, 2023. This was the third launch of the Shenlong spacecraft, with the first two occurring in 2020 and 2022.

China has now launched Shenlong into Earth’s orbit for the third time, but there is still little information about the mysterious spacecraft. It is known that it works in an orbit of approximately 600 km and that communication with Earth most likely occurs at a frequency of 2280 MHz. From the experience of Shenlong’s first two flights, it is also clear that the secret spacecraft is designed for extended orbital missions: Shenlong’s second voyage lasted a total of 276 days, after which it landed on a specially modified runway on May 8, 2023.

Image credit: Erik Simonsen/Getty Images

If this information is correct, then Shenlong may be very similar to the American Boeing X-37B reusable spaceship, whose demonstration flights have been observed in recent years.

In the first week after Shenlong’s most recent launch, observers noticed that it released 6 unidentified objects during its orbit, which, upon further analysis, turned out to be inert debris that accidentally reflected a signal from satellites operating near Shenlong’s flight area. During Shenlong’s first two flights in 2020 and 2022, independent observers observed mysterious objects orbiting alongside the main spacecraft, having possibly been released from the vehicle. At that time, experts concluded that Shenlong likely launched small satellites, service modules, or simply a simulated payload.

However, the lack of information from official Chinese sources and the general veil of secrecy that surrounds its space program means that both the basic purpose of the Shenlong itself, as well as its potential payloads, are unknown. Officially, Beijing continues to claim that it is carrying out the Shenlong demonstration flights with the aim of “conducting verification of reusable technology to ensure the peaceful use of space.” However, increasing tensions in Asia, particularly around the Korean Peninsula and the island of Taiwan, suggests that the main mission of the new Chinese spacecraft is likely military.

The development of the Chinese launch vehicle fleet and the problem of toxic fuels

While the Shenlong spacecraft is currently being launched into low Earth orbit by the Long March 2F rocket, China continues to expand its fleet of launch vehicles, focusing on the development and implementation of reusable modules. Today, there is fierce competition among the country’s private rocket-building companies to see whose VTVL rockets will become China’s equivalent of the Falcon 9, ensuring the capability for easy and large-scale deployment of satellite mega-constellations.

In 2023, the Chinese aerospace company CAS Space demonstrated the successful landing of its experimental VTVL module, which successfully touched down on a sea platform from an altitude of nearly 1 km. The landing speed of the module at the final stage of descent was 2 m/s.

Credit: CAS Space

Elsewhere, CAS Space has developed the solid-fuel rocket Lijian-1 (also known as Kinetica-1), which in January 2024 launched a payload of 5 satellites into orbit. Among them was Taijing-4 03, a satellite equipped with a synthetic aperture radar and a processor that employs artificial intelligence algorithms for faster target detection on Earth. In 2025, CAS Space plans the first demonstration flight of its new solid-fuel rocket Lijian-2, which will be capable of delivering 7.8 tons to a sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) or 12 tons of payload to low Earth orbit (LEO). It is anticipated that the initial versions of Lijian-2 will be expendable, but by 2027 CAS Space promises to equip the rocket with a reusable first stage capable of vertical landing.

Galactic Energy is another Chinese company competing in the development of reusable launch vehicles. This startup is creating the reusable Pallas-1 rocket, which features kerosene-oxygen rocket engines produced by Cangqiong. The first demonstration launch of Pallas-1 is expected to take place at the end of 2024. The rocket will be capable of delivering up to 3 tons of payload to SSO and up to 5 tons to LEO.

The private aerospace company iSpace has also scheduled the launch of its reusable Hyperbola-3 rocket, which uses liquid methane and oxygen (methalox) fuel, for 2025. This rocket has a payload capacity of up to 8.5 tons deliverable to low Earth orbit (LEO). Another notable methalox rocket is the Zhuque-3 from Landspace, which we previously discussed in the context of its deployment of satellite mega-constellations.

Gravity-2, developed by Orienspace, is expected to be the true heavyweight in China’s rocket industry. The company claims that its latest rocket will be capable of delivering up to 25.6 tons of payload to low Earth orbit using rocket engines that run on kerolox (a mixture of kerosene and liquid oxygen). A similar fuel mixture will be used in the reusable Tianlong-3 rocket from Space Pioneer, which will closely resemble SpaceX’s Falcon 9 in design.

Regarding China’s use of rocket fuel, it is worth noting that in the race for new space achievements, Beijing has prioritized neither the safety of its citizens nor environmental protection. The country continues to use hazardous fuel mixtures, such as nitrogen tetroxide, liquid hydrazine, and red “smoky” nitric acid, to launch rockets from deep inside mainland China, rather than from coastal areas as Western countries do. As a result, in the event of accidents, debris from dangerous rockets falls near populated regions, contaminating the surroundings with toxic chemicals.

It is worth noting that, in the mid-20th century, American rocket manufacturers also experimented with hazardous “smoky” nitric acid, but discovered its harmful effects on the human body. As a result, more environmentally friendly rocket fuel alternatives eventually replaced this fuel mixture, whose name comes from the reddish-orange haze it produces.

However, during this period a Chinese scientist, Qian Xuesen, was working with American counterparts testing various hazardous fuels. He was later detained by U.S. intelligence agencies on suspicion of collaborating with the Chinese government. Subsequently, he was deported to China, where, drawing on his experience in the United States, he came to lead the Chinese space program. The dangerous direction of Beijing’s rocket development industry, which continues to fuel Chinese rockets with simple, cheap, and highly toxic propellants, is largely a result of his decisions.

The use of hazardous propellants, the development and demonstration of anti-satellite weapons (the latest documented test dates back to 2007), and attempts to place nuclear weapons in orbit all indicate that Beijing is seeking not entirely peaceful dominance in the global space sector. The increasing militarization of space activities is evident not only in the implementation of new military space technologies but also in the active restructuring of the PLA’s space forces, with organizational and management models being borrowed from its main strategic competitor, the United States.

Division of duties: Three instead of one

The latest large-scale restructuring of the Chinese military, which began in the spring of 2024, has introduced several new cybersecurity units, including those focused on space operations.

Since launching a complete reorganization of the People’s Liberation Army in 2015, China has made significant advances in strategic management and organization. Notably, this large-scale reform led to the establishment of the Missile Forces and later the Strategic Support Forces (SSF), which were tasked with managing military space operations, cybersecurity, and electronic warfare. However, at the beginning of 2024, the role of the SSF as a single structure responsible for strategic military operations was reconsidered.

On April 19, 2024, the National Military Academy announced the division of the Strategic Support Forces into three independent units: the Air and Space Forces, the Cyberspace Forces, and the Information Support Forces. These three entities, along with the Logistics Forces (which focus on military logistics and support), will form the PLA’s auxiliary forces. Their task will be to support the four main PLA forces, which continue to be the Ground Forces, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Missile Forces.

The newly established Air and Space Forces will be responsible for organizing the interaction between Chinese aviation and space forces. This new division will handle every aspect of China’s military space activities, from launching satellites and spacecraft into orbit and managing their orbital operations to ensuring their safe return to Earth (deorbiting). The Information Support Forces will be tasked with constructing and implementing an integrated network information system designed to provide a resilient and reliable exchange of information between key elements of the PLA. The Cyberspace Forces will focus on defending against cyberattacks, conducting intelligence operations, and engaging in electronic warfare.

The reorganization of the People’s Liberation Army and the disintegration of the SSF are likely aimed at making each department more independent, while also enhancing the quality of their specialized expertise. As can be seen, China is not only adopting the American model of involving business in strengthening national security but is also effectively copying its key organizational structures. The newly established Air and Space Forces of the PLA have much in common with the U.S. Space Force (USSF).

Although only 10 years have passed since its most recent reforms, Beijing has demonstrated a clear ability to assess the major weaknesses of its military and remove obstacles. This has resulted in the recent purge of senior leadership in the Strategic Support Forces, which ultimately led to the dissolution of the SSF altogether. Purges are also occurring at the top management level of critical defense-related companies. China has replaced three times as many top managers in the military sector in 2024 as compared to 2023. This could indicate that corruption in large defense contracts remains China’s Achilles’ heel, despite severe penalties (including the death penalty) for such activities.

Time will tell how well the new auxiliary units of the PLA perform, but the mere fact of their existence demonstrates that China continues to carefully analyze military threats and is not shying away from borrowing management and organizational models from its main strategic competitor.