On August 22, 1976, the Luna-25 descent capsule landed 200 km southeast of Surgut in central Siberia. This event marked the close of the Soviet lunar program. Despite the fact that the Lunokhod-3 (Lunar Rover 3) craft was assembled and cleared for flight into space, the USSR never again carried out launches to the Moon.

In turn, NASA switched off all their instruments left by the astronauts of the Apollo expeditions on the moon on September 30, 1977, thus marking the symbolic end to America’s part of the lunar race. After that, the US and Soviet space programs seemed to forget about the Moon. In the 1980s, they built reusable ships, launched spacecraft to other planets, and flexed their military muscles, creating various space weapons systems. The Moon, however, had fallen out of the superpowers’ interest. It was almost two decades before the situation began to change again, little by little.

Heirs of the Cold War

The first lunar mission since 1976 was implemented by a new space player – Japan. In the late 1980s, many experts fully expected that in the near future, Japan would become a new superpower that would be able to challenge America globally. In this context, the launch of the Japanese spacecraft to the Moon looked like a very symbolic step.

It worked out pretty well for a first attempt. Launched in 1990, the Hiten spacecraft successfully tested the technology of aerial braking in the earth’s atmosphere, completed a series of flights around the Moon and launched a mini-probe (though it failed shortly after separation). However, shortly thereafter, the Japanese economic miracle came to an end. The mission which was widely perceived as the Land of the Rising Sun debuting as a major space player was consigned to remain only a tentative first step for a long time.

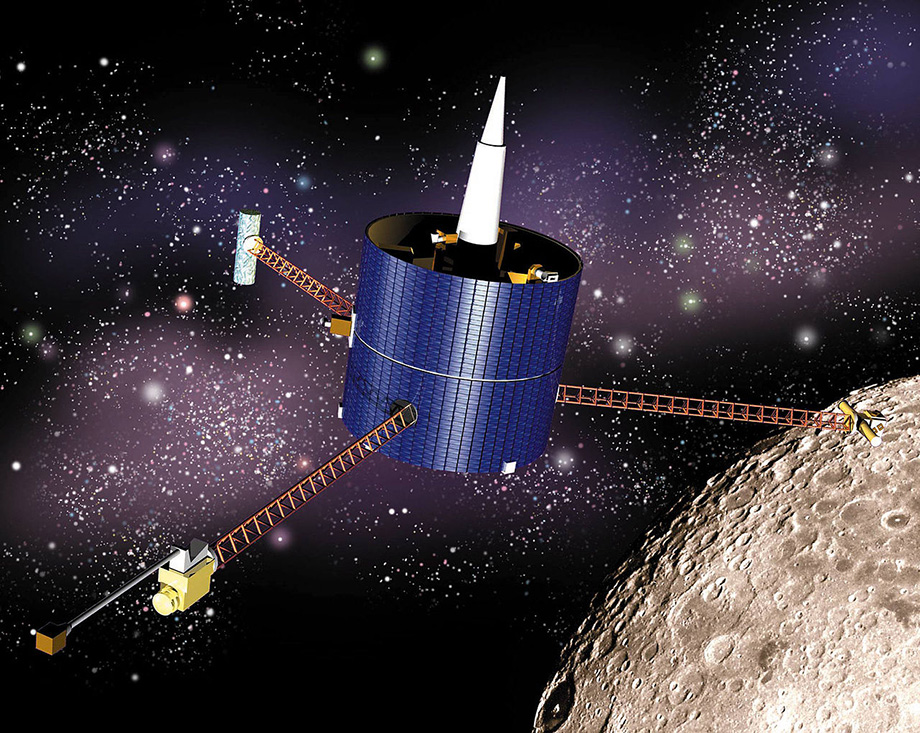

A much more important role in the return of interest in the Moon was played by the American Clementine mission. It was a very unusual project that came about largely as a result of the end of the Cold War. Initially, the Clementine spacecraft was supposed to test technologies for detecting Soviet ballistic missiles. After the collapse of the USSR, however, the original mission of Clementine had suddenly become far less relevant. At the same time, NASA was strapped for resources, as well, since funding for its programs had been decreasing for some time, which left the organization unable to carry out new missions.

In this situation, NASA and the US military came to a mutually beneficial agreement. They decided to pool their resources and use Clementine as both a scientific probe for interplanetary research and a tester of new technologies. The device was launched in January 1994 (incidentally, on a converted ballistic missile), after which it made several flights by the Moon.

Subsequent analysis of Clementine’s data offered a big surprise. During one of its flights by the Moon, Clementine scanned its south pole with radar. After studying the characteristics of the signal it reflected, scientists found that there were indications of ice at the bottom of the Moon’s deepest polar craters, which are never illuminated by the sun’s rays.

It is worth saying that the presence of ice at the lunar poles has been suggested back in the 1960s. Moreover, analysis of a regolith sample delivered by Luna-24 once unexpectedly showed the presence of water. But only after the Clementine mission did scientists start seriously talking about the possibility of ice deposits on the Moon. The probe’s data actually woke up the scientific community. It turned out that Earth’s nearest neighbor still held many secrets, and there was only one way to reveal them.

The beginning of the lunar renaissance

In 1998, NASA launched their Lunar Prospector spacecraft. It was the first full-fledged lunar mission from the US in a quarter century. Over the next year, Lunar Prospector successfully completed its scientific mission, taking many readings. The data it collected unequivocally confirmed Clementine’s find; there were indeed reserves of water in the polar regions of the Moon.

Curiously, even the conclusion of the Lunar Prospector mission was planned so that it could check for the presence of ice on the Moon one last time. The device was deliberately directed into a circumpolar crater in the hope that the impact would eject a substance that would contain water. Unfortunately, the experiment was not successful, as astronomers failed to record the cloud raised by the fall of Lunar Prospector. But despite this final misfire, the mission’s results were compelling enough to form a consensus in the scientific community that there was indeed ice on the Moon.

The return of interest in the moon fortunately coincided with progress made by a number of countries in space exploration. The Moon was an excellent testing ground for new space players to build and operate interplanetary vehicles. Thus, the first decade of the 21st century saw a whole series of debut lunar missions.

The first was the European spacecraft SMART-1, launched in 2003. It completed its scientific mission and tested several new technologies, including an experimental electric propulsion system. It was followed by China’s Chang’e-1 and India’s Chandrayan-1. They entered lunar orbit and successfully carried out work there for several years. Chandrayan-1 even repeated the Lunar Prospector’s experiment, dropping an impact probe into the Shackleton polar crater. This time, scientists were able to record the probe’s crash plume, and thus confirm the presence of ice.

After a long hiatus, Japan returned to the moon with the Kaguya spacecraft, – at that time the most complex and expensive spacecraft in their history. The probe met expectations with a rich harvest of scientific data. The ordinary public will remember it for its magnificent images showing the rise of the Earth over the lunar surface.

NASA has also sent several spacecraft back towards the Moon, the most famous of which being the LRO. Thanks to the LRO’s onboard camera, it was able to photograph the landing areas of the Apollo expeditions and the tracks left by the astronauts, as well as to find the landing sites of the Soviet spacecraft Luna and Lunokhod.

The next decade of lunar study was dominated by China. In 2010, they sent their Chang’e-2 spacecraft to the Moon. Its main goal was to find a suitable landing site for the next Chinese lunar mission.

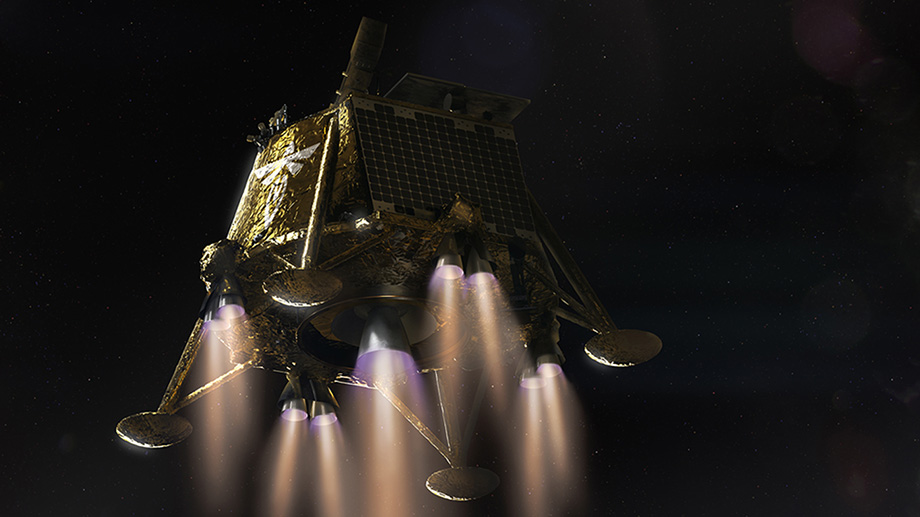

Chang’e-2 achieved its mission, which allowed China to move to the next phase of its lunar program. In December 2013, “Chang’e-3” became the first visitor from Earth since 1976 to make a soft landing on the surface of a satellite of our planet. It delivered not only a platform with scientific instruments, but also the 140-kilogram rover Yutu, the first wheeled vehicle on the Moon since Lunokhod-2.

If the early Chinese lunar missions were a repetition of old Soviet and American achievements, then the Chang’e-4 showed that China has moved on to conquering new milestones. In January 2019, Chang’e-4 became the first vehicle in history to make a soft landing on the far side of the moon. From a technological point of view, this was a daunting task. To ensure the landing, China had to first put a special relay satellite into an orbital position from where both our planet and the far side of the moon can be seen at the same time. This significantly increased the total price of the mission, but the PRC did not skimp on the costs.

Like its predecessor, Chang’e-4 also carried a lunar rover on board. In addition, as part of the mission, the Chinese carried out a rather curious experiment to try creating a closed biosphere in a sealed cylinder. It ended in partial success: a camera installed inside the cylinder recorded the germination of a cotton seed. This is the first time in history that a plant has sprouted on another celestial body.

In 2019, India tried to make their own move with the Chandrayan-2 mission. However, while its orbital module successfully entered selenocentric orbit, the lander with the first Indian lunar rover Vikram unfortunately crashed.

China, on the other hand, has continued to methodically conquer the Earth’s nearest neighbor. In 2020, they launched their new Chang’e-5 spacecraft, which successfully delivered the first lunar soil sample in the 21st century back to Earth. Next up for China is a mission to deliver a sample of regolith from the South Pole, scheduled for 2024.

Private Companies on the Moon

In 2007, the nonprofit organization XPrize and Google launched the Google Lunar X PRIZE. It will be awarded to the team that would be the first to build and land a self-propelled vehicle on the lunar surface, travel 500 meters, and transmit high-definition video and images back to Earth. However, after a number of deadline extensions, the contest ended in 2018 without a winner. It proved far more difficult than the organizers anticipated.

Nevertheless, Google Lunar X PRIZE played an important role in the further history of the space industry. After the end of the competition, some of the teams participating in it decided to continue working on the creation of their lunar craft anyway, intending to see their work through to the end. Finally, the Israeli SpaceIL managed to do it; in February 2019, their Beresheet probe became the first private vehicle in history to travel to another celestial body and successfully orbit around it.

Unfortunately, the Beresheet’s attempt to land on the moon in April 2019 ended in failure due to a malfunction of its inertial sensor. The main engine shut off prematurely and eventually the probe crashed around an area known as Mare Serenitatis (Latin for Sea of Serenity). Nevertheless, the Beresheet spacecraft clearly demonstrated that we have entered a new era in which private companies are able to build their own spacecraft and then launch them to the Moon on private rockets.

NASA was the first space agency to take advantage of this trend. Several years ago, it announced the launch of its CLPS (Commercial Lunar Payload Services) initiative, aimed at attracting commercial firms into lunar development. Its essence is quite simple: NASA provides fixed-price contracts for cargo to be sent to the moon, while the company receiving the contract independently organizes the entire delivery process, finding an available launch vehicle, buying or building a descent vehicle, and ensuring the placement of cargo. This way, NASA frees itself from numerous organizational and technological concerns while supporting the development of the private industry. The typical contract amount under the CLPS program is about $80-90 million.

NASA has already issued seven CLPS contracts. They were received by Intuitive Machines, Astrobotic Technology, Firefly Aerospace, and Masten Space. If all goes according to plan, the first private cargo missions to the moon by Intuitive Machines and Astrobotic Technology should start as early as 2022, with Firefly Aerospace and Masten Space following in 2023.

However, the CLPS program is not the only support option private industry has to get to the moon. Another way is to conclude contracts to launch operators, as was done by the US-New Zealand Rocket Lab. The company received a contract from NASA to launch their experimental CAPSTONE satellite. The device will test the stability of the orbit into which the LOP-Gateway orbital station is planned to be launched in the future, as well as test an autonomous navigation system. At the moment, the launch of CAPSTONE is scheduled for March 2022.

The Artemis Program and the Planned Return of Humans to the Moon

CLPS and similar initiatives are not an end in themselves for NASA. Rather, their aim is to simplify the main task of returning people to the moon. This time, however, missions would not aim for astronauts to stay for just a few days, but rather to establish a long-term presence.

It all began in 2017, when the administration of the newly-elected US President Donald Trump buried a project which had been developed by his predecessor to organize a manned expedition to a near-earth asteroid, which was planned to be transferred to a circumlunar orbit. Instead, officials decided to use the SLS super-heavy rocket and the Orion spacecraft to organize landings on the moon, followed by the creation of a base in the South Pole region – somewhere near the deposits of ice, which would greatly simplify the task of organizing a long-term human presence.

Initially, the first manned American landing on the moon in the 21st century (the Artemis III mission) was scheduled for 2028. But in 2019, the Trump Administration decided to speed up the program and announced its intention to achieve this goal by 2024. However, the US Congress did not share this enthusiasm, and did not provide Artemis with the necessary additional funding, which in fact put an end to the entire initiative. NASA recently announced the expected postponement of the Artemis III mission to 2025. However, according to a number of recent expert assessments, this date is likely to be repeatedly shifted further and further back. Thus, it is possible that the ultimate return of humans to the moon will occur in 2028, as originally planned.

Another important element of the American lunar program will be the LOP-Gateway orbital station mentioned earlier. In addition to NASA, the space agencies of Europe, Canada, and Japan will take part in this project. As of today, the launch of the first two elements of the station (an electric motor module and a small living compartment) is scheduled for the end of 2024.

The US isn’t the only space power with plans to land people on the Moon. China also has its own lunar project, and is developing its own super-heavy rocket and components of a manned system capable of delivering taikonauts (the term for Chinese astronauts) to the moon. This year, China signed an agreement with Russia on the creation of a joint lunar station.

Due to the traditionally secretive nature of the Chinese space program, it is still difficult to name any specific dates when the taikonauts will be able to plant China’s red flag on the moon. By most estimates, however, it could happen as early as the early 2030s, and perhaps even earlier. Thus, should there be further delays in the Artemis program, China has an excellent chance to lead the second lunar race.

Much will depend on the result of the two tests which will take place next year. The first will be the Artemis I mission, in which NASA will test their SLS super-heavy rocket and Orion spacecraft in full configuration for the first time. The device will have to achieve orbit around the Moon, and then return to Earth. The second milestone will be the first orbital test of SpaceX’s Starship. It was recently chosen by NASA as their vehicle for delivering American astronauts to the lunar surface.

But no matter how the first flights of the SLS and Starship end up, one thing can be predicted with confidence: in the coming years, we’re going to be seeing a lot more of the Moon in our headlines.