The driving engine of the NewSpace economy

Not so long ago, we talked about the NewSpace economy – in other words, the space services market, the global turnover of which is currently about $350 billion.

One of the key segments of this market is the launch services industry, responsible for launching and transporting goods into orbit. Today, the market as a whole is valued at $9.88 billion. However, according to a study conducted by Allied Market Search, this figure will increase to $32.41 billion by 2027 (provided that the level of annual investment growth of 15.7% is maintained per year).

Our editorial team has prepared a detailed analysis of the launch services market and is ready to introduce you to both its most venerable players and a number of dark horses to keep an eye on, as this industry continues to mature.

Key segments of the orbital launch services market

In order to better understand the structure of the launch services market, we will divide it into key segments.

The payload segment is the threshold value for the mass of cargo that the launch vehicle can deliver into orbit (taking into account the mass of its launcher and the fuel required to launch).

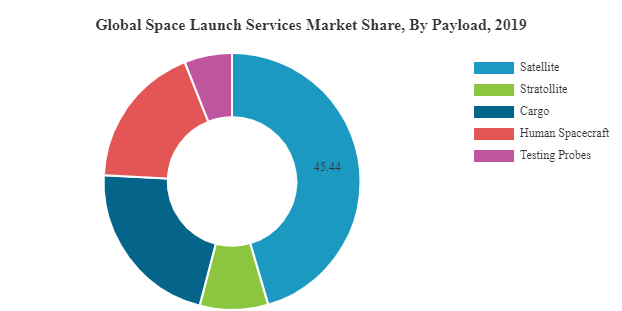

The launch services market covers the need for launching five main types of equipment into orbit:

- Satellites account for about 45% of annual space launches.

- Various cargo – their delivery (mainly to the ISS) accounts for about 22% of launches.

- Spaceships and modules are another in-demand area of the launch services market, accounting for about 17% of all missions.

- Test probes – 6% of all space launches are used to put them into orbit.

- Stratollites. By their design features, stratollites are analogous to a space balloon intended for research and meteorological work in the upper atmosphere – the stratosphere. These types of missions not only offer a variety of prospects but are also much cheaper than orbital missions: the cost of launching one stratollite is on average 100 times lower than one communication satellite. Although the launch of such a balloon does not require a traditional launch vehicle, stratollite delivery is common as a space launch service, since their use is in many ways similar to traditional satellites.

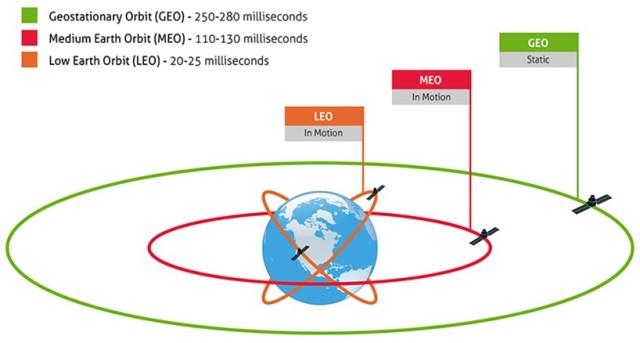

Another key aspect of the space launch market is the levels of near-Earth orbits to which satellites, space modules, and cargo can be delivered:

- Low Earth Orbit (LEO) – orbital altitudes range from 200 to 2,000 km above sea level.

- Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) – 2,000 to 20,000 km above sea level.

- Geostationary Orbit (GEO) and Geosynchronous Orbit (GSO) – both orbits are located at 35,786 km above sea level. However, in a geostationary orbit, the satellite moves synchronously with the Earth’s rotation speed and in the same direction. Due to this, the satellite hovers permanently over one point on the planet. The rotation speed of a geosynchronous orbit is also equal to one day, with the only difference being that the satellite’s motion vector is not tied to the Earth’s rotation vector. Because of this, the satellite does not hang in one position above the planet and can move along any given orbital trajectory.

Currently, the delivery of satellites and cargo to low-Earth orbit is considered one of the cheapest and most in-demand areas of the launch services market. This is primarily due to the low fuel consumption needs for launch vehicles to reach that orbit, and the moderate cost of manufacturing the launch vehicles, typically rockets, themselves. That is why many modern space startups (about 75%) are betting on conquering LEO: both investment risks, and financial costs, are significantly lower there.

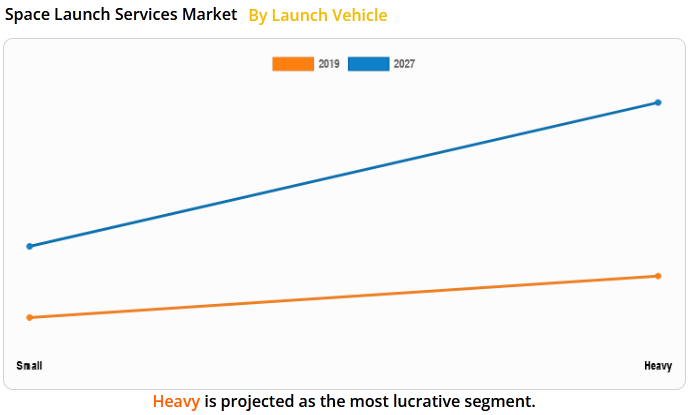

In addition, it is customary to segment the space launch market by the type of launch vehicles used. Their classification is presented below:

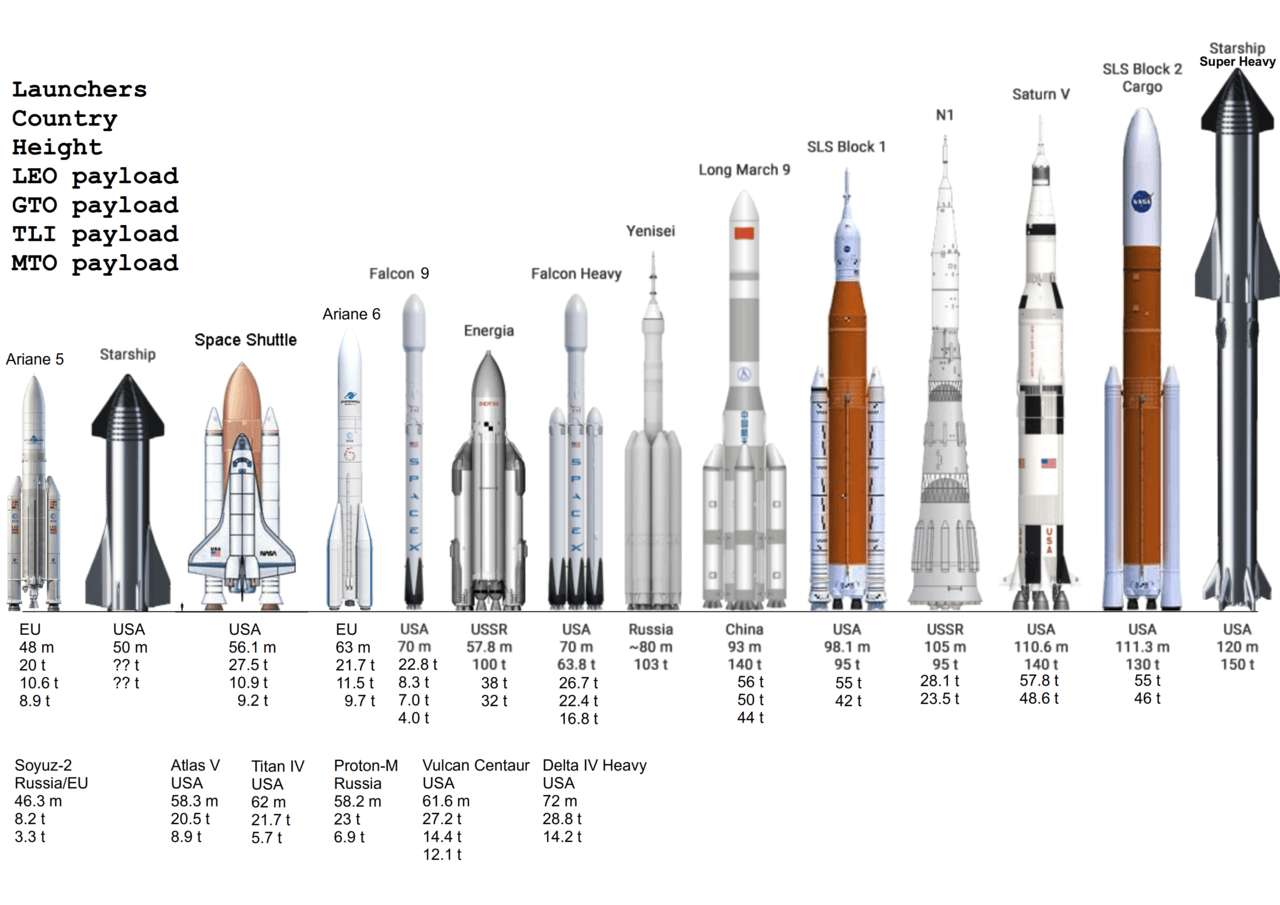

- Lightweight launch vehicles – less than 2-ton payload (Vega from Arianespace, Alpha from Firefly Aerospace).

- Medium-duty launch vehicles – with payloads from 2 to 20 tons (“Soyuz-2”).

- Heavy-duty launch vehicles – with the ability to carry from 20 to 50 tons of cargo (Ariane 5, Falcon 9).

- Super-heavy launch vehicles – with payloads exceeding 50 tons (Falcon Heavy and Saturn-5).

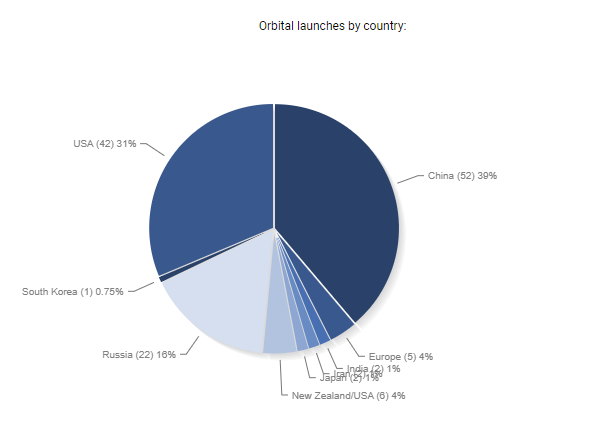

The space launch market is also characterized by regional divisions. At the moment, China can claim to be the market leader, with 39% of launches being handled by Chinese-based companies. The United States is the runner-up, with 31% of launches. and Russian and European launches account for only 20% of the market combined (16% and 4%, respectively).

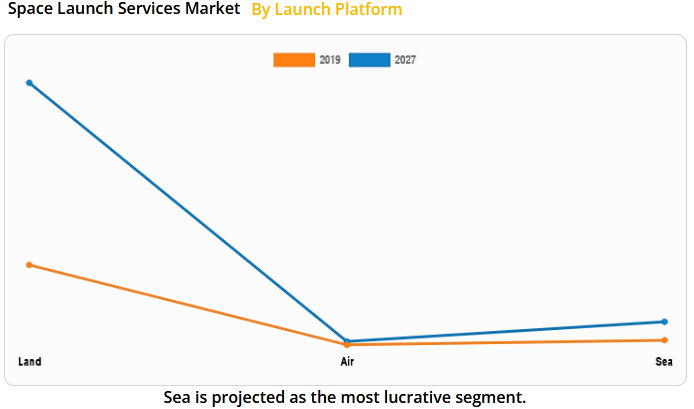

The launch services industry is also subdivided into the platforms from which launches are carried out:

- Ground – Ground-based launch pads.

- Surface – floating launch pads.

- Air – using an aircraft as a launchpad.

The space launch services market is quite multifaceted and includes many branches and nuances. However, to better understand the development trajectory of the current NewSpace industry, it’s worth first digging into its history.

The emergence and development of the space launch services market

The conditions for the formation of a commercial space launch market first began to crystallize around the 1950s, during the heyday of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union and the birth of human rocketry in general. The space race between these two countries gave rise to closed markets, which worked according to a simple formula: “state money for the implementation of state-space programs.” The rockets and technologies used to develop space capability remained the sole property of their respective nation-state and were often considered a critical component of national security.

However, this situation changed dramatically in the 80s. In France, private company Arianespace was admitted to the non-military segment of the space market, which provided services for the launch of communications satellites into low-earth orbit. It was Arianespace’s experience, and the private companies that followed, that laid the foundation for our current, competitive launch services market. This competition only really kicked off, however, at the turn of the new millennium.

The turning point in the development of the commercial space launch services market came on December 3, 2013, when SpaceX successfully launched a 3.2-ton SES-8 communications satellite into the geo-transfer orbit (GTO). The launch vehicle was a Falcon 9 v1.1, with a GTO payload of 4,850 kg; and 13,150 kg for low earth orbit (LEO).

The Elon Musk-founded company set an interesting precedent: by significantly reducing the cost of launching launch vehicles, it spurred a number of other commercial entities and investors to join the new space race, emboldening them to challenge such industry giants as the French Arianespace and the American United Launch Alliance (ULA) – though far from all succeeded.

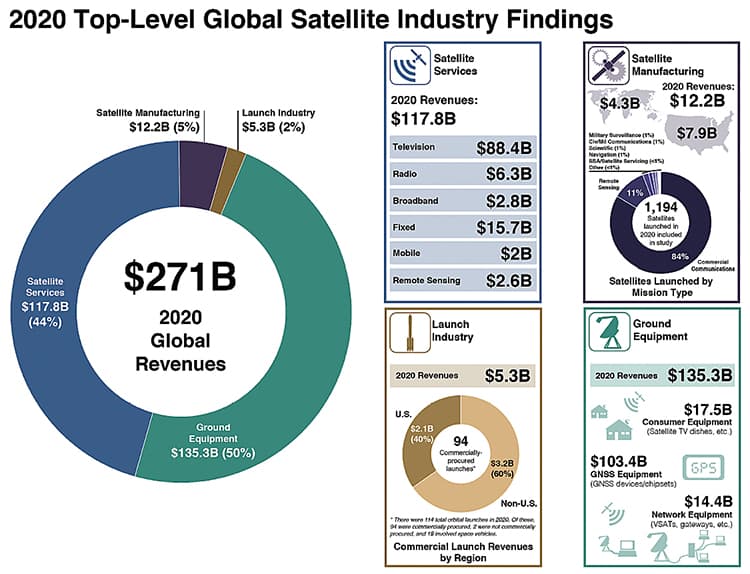

According to the analytics and engineering firm Bryce Space and Technology, in 2021, there were 165 leading commercial launch services companies – but only seven actually launched satellites and cargo into orbit. That is not a lot – considering that in general, about 75 percent of the entire NewSpace economy (approximately $271 billion) is in the business of creating, maintaining, and launching satellites into orbit.

However, the picture becomes a little less rosy if launch and cargo delivery is considered as a separate industry: in this case, its global turnover amounts to only $5.3 billion (proceeds from the 94 successful launches in 2020).

Obviously, this is too small a piece of the pie for any significant amount of hungry mouths – the competition in the launch services market is very tough, yet every year brings in new blood and new firms willing to take on the challenge.

How SpaceX made launching cheap(er)

It can be said that SpaceX revolutionized the field of commercial launch services by innovating significant cost reductions for launching cargo and communication satellites into low-Earth orbit thanks to the addition of return modules in their Falcon 9 rockets. These modules allowed SpaceX to reuse their launch vehicles, opening up notable savings on operational and launch costs. By 2013, the average price tag for a SpaceX launch to geo-transfer orbit was $15 million lower than that of their direct competitors from Arianespace. At first, Musk was accused of dumping (artificially lowering) prices for launch services, but over time, competitors have recognized the obvious: to compete with SpaceX, you first need to start with yourself.

Citing Musk’s positive experiences, ULA and Arianespace have announced a reorganization of their services and announced their intent to release new classes of launch vehicles that will compete with Musk’s Falcon in the next decade.

It isn’t just the addition of return modules to launch vehicles that have led to price reductions for satellite and cargo launches. According to Bryce Space and Technology, about 75% of companies involved in the delivery of goods into orbit rely on the construction of small launch vehicles. This is where miniaturization plays a role – the smaller other components of the launch vehicle are, such as sensors, the more payload can be carried to orbit. Thanks to this, smaller vehicles become capable of carrying a large payload at the same fuel consumption. In addition, light and ultralight launch vehicles are clearly cheaper to manufacture and operate.

The development of new fuel types for launch vehicles has also significantly contributed to launching cost reductions. For example, SpaceX’s Starship super-heavy rockets have a mass of 4,800 tons. 78% of the fuel for Super Heavy rockets is oxygen, with methane making up only the remaining 22%. For a single launch, Starship consumes $500,000 of fuel, and its payload for launching cargo into low-Earth orbit is 150 tons. SpaceX claims that with a high frequency of Starship launches, the cost of every 150 tons of cargo delivered to orbit could be as little as $1.5 million (approximately $10 per kg of payload). These numbers may seem a little fantastic, but Musk insists these prices can be reached by livestreaming Starship launches. For comparison, delivering 150 tons of cargo currently via the super-heavy Falcon Heavy will run a price tag of at least $70 million.

For all of NewSpace’s innovations, however, cost reductions of this scope are not common. In 2020, NASA decided to increase the cost of sending commercial cargo to the ISS from $3,000 to $20,000. At the same time, it will be necessary to pay twice as much for the return delivery of cargo to Earth: $40,000 instead of $6,000. Nasa explained that the prices “not reflected in full the cost of using NASA resources and were used primarily to stabilize this market segment”.

NASA’s new pricing policy successfully motivated several independent commercial space companies to devote themselves to the issue of rising prices for orbital cargo delivery, which resulted in a number of successful space startups and interesting engineering solutions, such as the creation of hybrid engines.

Private space companies and promising startups

In the NewSpace field, there are dozens upon dozens of bright-eyed startups and firms all vying for a piece of one of the most cutting-edge and technologically innovative markets on the planet. Covering all of them may be beyond the scope of this article – but here are the highlights of the biggest and most promising players in the industry.

Firefly Aerospace is an American company headquartered in Austin, Texas. It currently has two light and medium-duty launch vehicles in its arsenal: Firefly Alpha, which has been certified and put into production, and Firefly Beta, which is under development. The payload capacity of the Firefly Alpha light rocket is 1 tonne of payload, and the Firefly Beta prototype will be able to carry up to 8 tonnes of cargo to LEO, and up to 6 tonnes of cargo to HEO. In addition, Firefly Aerospace has already secured a $93.3 million contract with NASA to deliver cargo to the Moon as part of the Artemis project. That launch is scheduled for 2023.

ABL Space Systems – founded in 2017, this LA-based company was until recently considered a dark horse in the launch services market. That all changed this year when ABL Space Systems signed a contract with U.S. defense concern Lockheed Martin for 58 launches of its RS1 small launch vehicle. The launches are scheduled to take place over the next decade. In addition, a number of contracts have been concluded with the U.S. Air Force and private company L2 Aerospace, which will likely be the main clients for the production and operation of the RS1 multipurpose two-stage rocket. The rocket has a payload of 1,350 kg, which the RS-1 will be capable of placing into low-Earth orbit for $12 million per launch. Thanks to these contracts, ABL Space Systems’ capitalization has increased significantly and is currently estimated at $1.3 billion.

SpaceX is one of the most commercially successful space companies in the world. In September 2021, this American company, founded by entrepreneur Elon Musk, became the first commercial company to successfully send a crew of NASA astronauts to the ISS on its Crew Dragon spacecraft. In addition, it launched over 1,000 communications satellites into orbit last year as part of its Starlink global internet program. 2020 also marked the Falcon 9 rocket’s seventh flight, which clearly demonstrated the long-term viability of reusable space modules.

Isar Aerospace is another example of a successful start-up, this time from Germany, with famed automobile brand Porsche among its main investors. The brainchild of Isar Aerospace is the Spectrum, a two-stage low-payload launch vehicle capable of delivering up to 1,000 kg of cargo to LEO. Last year, the company was able to attract $187 million in investment. Industry watchers will have a chance to judge whether these investments will pay off very soon: Spectrum’s first launch is scheduled for the end of 2022.

Arianespace is a true veteran of the market, having been engaged in commercial launches since the mid-80s, and will soon conduct its 300th successful launch. Recently, the company underwent a management reshuffle, merging the company into the larger Ariane Group (which also includes the French aerospace firm Airbus). The Arianespace rocket fleet has three carriers: the light Vega, the medium Soyuz-2, and the heavy Ariane 5. Ariane 5 has actually established itself as one of the most reliable rockets in history, having completed 81 successful launches in a row.

United Launch Alliance is a joint American venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Founded in 2006, the company has three main types of launch vehicles in its rocket fleet: Atlas-5 (one-time two-stage medium-lift missile), Delta-2 (medium-light launch vehicle, which is now being phased out), and Delta-4 (which is produced in several versions, from medium to heavy). Delta-4 also uses cryogenic components in its fuel: liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. Today, ULA performs about 10 launches per year. But the number of planned launches has dropped by almost a third-ever since SpaceX received permission to carry out government launches.

Gilmour Space Technologies is an Australian company headquartered in Brisbane. Her story began in 2012. Over the past year, Gilmour has raised about $65 million in investment to develop its solar-synchronous orbit (SSO) launch program for Eris lightweight rockets, with a payload of 215 kg. The main difference between Eris and its direct competitors is the presence of a hybrid engine in its launcher, which allows operators to reduce the use of chemical fuels – significantly reducing the cost of launch.

Skyroot Aerospace is the first commercial Indian NewSpace company, founded in 2018 by two scientists who were previously involved in the Indian National Space Program. At the beginning of this year, the company received $11 million in funding, and by May this figure reached $14.9 million. Skyroot Aerospace is developing a Vikram rocket, which will be capable of launching up to 315 kg of cargo into low-Earth orbit, and up to 225 kg into geostationary orbit. The company has now completed ground tests of the first stage rocket engine and is looking forward to the first flight tests.

Blue Origin is an aerospace company founded by American billionaire and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. Although Blue Origin is not involved in space-based cargo transportation and satellite launches, its successes should be mentioned. In July 2020, its six-seat New Shepard spacecraft achieved its first suborbital flight and reached an altitude of 100 km. New Shepard consists of two modules: a rocket launcher and a space capsule with a capacity of up to six people. In addition, NASA has recruited Blue Origin to create manned lunar modules as part of the Artemis program, and Bezos himself recently announced his ambitious plans to create a commercial orbital space station – Orbital Reef.

Virgin Galactic is a company headed by American billionaire Richard Branson and headquartered in New Mexico, and is a direct competitor to Blue Origin in the suborbital tourism market. Its arsenal includes not only the manned Spaceship 2-class VSS Unity spacecraft but also the ultra-low-payload launch vehicle (200 kg) LauncherOne, which is being developed by Virgin Orbit, part of Branson’s Virgin Group. The first commercial launch of the LauncherOne rocket occurred on June 30, 2021, and seven satellites were successfully delivered to orbit.

While some of these startups are still far from their first commercial launches, their developments have already set the trend of the launch services industry. Primarily, a trait these companies all share in common is a bet on the modularity and mobility of manufactured components, as well as the widespread use of advanced 3D printing technologies coupled with high-strength metals and alloys.

Trends and prospects of the launch services market for 2027

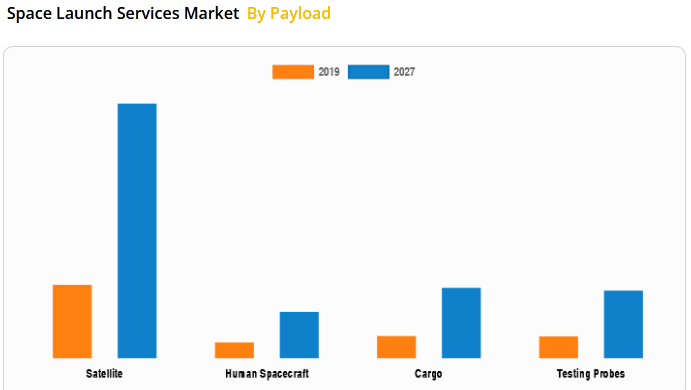

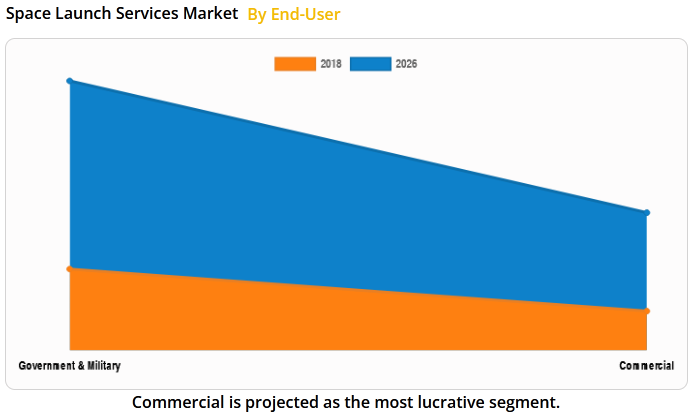

According to the results of studies conducted by Allied Market Research, by 2027, the existing positive growth rates of the launch services market are likely to continue.

An almost threefold increase in the number of satellites, cargo, manned spacecraft, and modules launched into orbit is predicted to occur, as well as a growing commercial interest in the use of stratollites.

Ground launches are expected to increase significantly over the next six years, with surface launches making up a smaller portion of launch technologies. Air launches will likely remain in their current position.

For commercial space launches, an increase in the use of super-heavy launch vehicles is projected. This is probably the result of NASA’s Artemis lunar program, as well as long-term plans for the colonization of Mars – which will likely require over one hundred tons of cargo simply for the creation of the initial bases.

Cost reduction trends for both component manufacturing and cargo delivery are likely to continue. In addition, the growth in investments both from government institutions and private investors has and will continue to have a beneficial effect on the development of the launch services market for space launches and cargo transportation.

Along with this, several factors have a significant negative impact on the industry. First of all, this is the high levels of initial outlays for launch preparations, as well as a noticeable shortage of qualified personnel. Another criterion inhibiting the growth of the industry is the increasing resistance to adapt to new technologies. Most investors are still afraid to invest their money in projects that are not only technically complex but prone to failure even with industry-leading staffing and equipment.