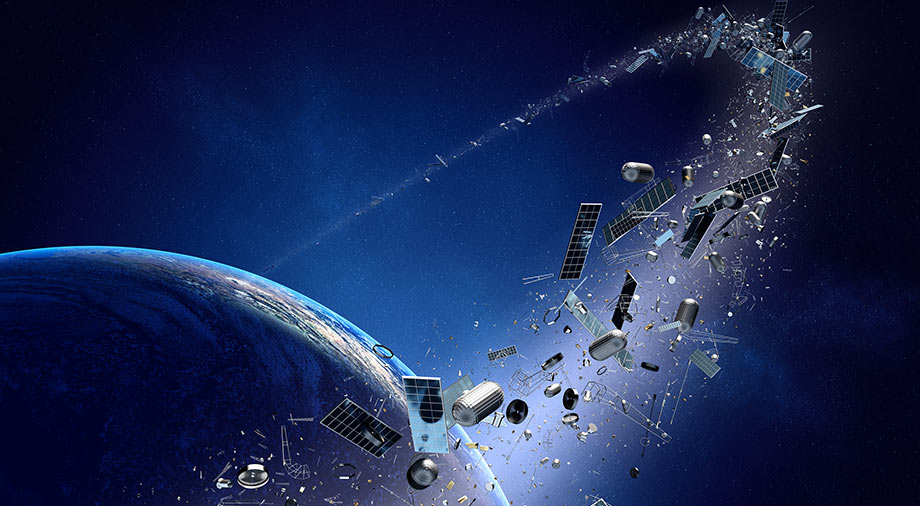

The Earth’s orbit is not what it was even a decade ago. These days, the International Space Station has to be on the constant look out for debris, and adapt in order to avoid a potentially fatal collision. At the velocities the ISS is working at, even a small screw can cause serious damage to the station’s hull.

According to different estimates, there are up to 250,000 objects in space. Most of these are the product of collisions or disused equipment. The issue may seem like “rocket science” and way too abstract in times of a real pandemic here on Earth, but scientists and satellite operators are already criticizing the irresponsible use of space. To what extent is congestion in space a problem today, and where can this lead in the future? Let’s consider the facts.

Since the first human-made satellite, Sputnik, was launched in 1957, only a few dozen were joining it in low Earth orbit (LEO) annually until 2010 says Supriya Chakrabarti, a professor of physics at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. For instance, in 1990, there were 464 active satellites around Earth. In 2020 and 2021 alone, 1,300 and over 1,400 respectively were put into space, taking the total to 7,500 active satellites in LEO as of September 2021, the United Nations’ Outer Space Objects Index states.

Naturally, space enthusiasts have no plans to stop in 2022. Donald J. Kessler, an American astrophysicist and former NASA scientist, foresaw this problem back in the 1970s when he focused on the study of space debris. He first presented his ideas in an academic paper titled “Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt.” which was published in 1978. His theory eventually came to be known as Kessler syndrome (or collisional cascading). In simple terms, he predicted that as more artificial satellites are launched into LEO, the likelihood of collisions between them will rise, eventually creating a halo of debris around Earth. His hypothesis is now materializing before our eyes with the number of satellite deployments growing exponentially.

Massive satellite constellations

Countries ranging from Japan to Algeria have plans to join in the ever-expanding satellite race. Although some missions may sound optimistic and many will fail, the idea of the current rapid pace of satellite deployment intensifying even further is worrying, given the current state of affairs.. One of the most surprising and ambitious declarations in this area, however, comes from a country that few may have expected.

Rwanda is not the first country to come to mind when we think of space-faring nations. But the African state has persisted in space exploration. As things stand, Rwanda launched only one satellite back in 2019. But its recent filing with the International Telecommunication Union raised a few eyebrows and angered established satellite operators: 327,230 orbitals in two constellations. At the time of filing, Rwandan authorities failed to indicate their motivations – aside from “making the country a hub for the African space industry” – and left even the African Union and South African space agencies “blindsided” by the move.

But it’s not just the countries that have such plans. Canadian company Kepler also filed a proposed system of 115,000 satellites, albeit through the German government. Even this number far exceeds the status quo. But at least Kepler provided an explanation for their actions: to bring in the Internet to space and provide real-time communications to other satellites.

On the other hand, companies like OneWeb and Elon Musk’s SpaceX with its Starlink service are concentrating on providing the Internet on Earth, catering to the needs of businesses and individuals respectively. The former has deployed 394 orbitals into space already and intends to have 648 operational satellites by 2022, with the next launches planned for January 2022. SpaceX currently has over 1,900 satellites in LEO. Interestingly, the satellites have recently had to dodge the Russian space station and allegedly forced the Chinese to maneuver to avoid a collision, resulting in Beijing complaining to the UN.

According to Steve Collar, chief executive of SES, these recent, seemingly overfull, filings stem from a lack of regulation on the part of the ITU, which doesn’t have the right to exercise enforcement. Given the circumstances, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission seems to have stepped up to the plate, assuming the role of the stricter regulator. At the same time, Mark Dankberg, chairman of Viasat, expressed hope that the issue may be resolved at the national level as proposed systems seek landing rights from national regulators, who in turn may be reluctant to grant landing rights to orbitals disproportionately occupying space.

It is clear that space is slowly but surely becoming a contested domain, with pioneers getting the biggest slices of the pie. So far satellite collisions have gone largely unnoticed, but the current rate of expansion threatens serious disruptions in everyday services such as ATM and GPS in the future.

How to clear an orbit from space debris

There is still hope for solutions to these growing pains, however. Japan is at the forefront of this battle. Japanese company Astroscale has already successfully tested its End-of-Life Services program by launching the ELSA-d mission in March 2021, designed to dock and remove debris from space.

Additionally, the Active Debris Removal project, aimed at taking care of larger pieces of debris, is also underway, with the ADRAS-J mission expected to start in 2023.

A satellite communications company, Sky Perfect JSAT, hopes to deploy laser satellites to destroy debris in 2026.

Japan has also been offering space junk solutions as early as 2014, when the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency announced plans for an electrodynamic tether, involving a mesh of aluminum and steel wires that would follow an unmanned spacecraft and use an electromagnetic field to gather pieces of debris that would then eventually be burned up.