The 60-year period during which the legislative and legal framework for streamlining activities in space was formed has led the entire sector into a classic jurisprudence trap. Excessive bureaucracy has given rise to a real “asteroid belt” of licenses and procedures that disrupt dozens of space launches every year.

In an effort to ease the bureaucratic constraints on the industry, officials are working tirelessly to create new laws and modify existing legal frameworks. But is this leading to even more “junk” in NewSpace’s legal orbit?

How realistic are fines for orbital debris?

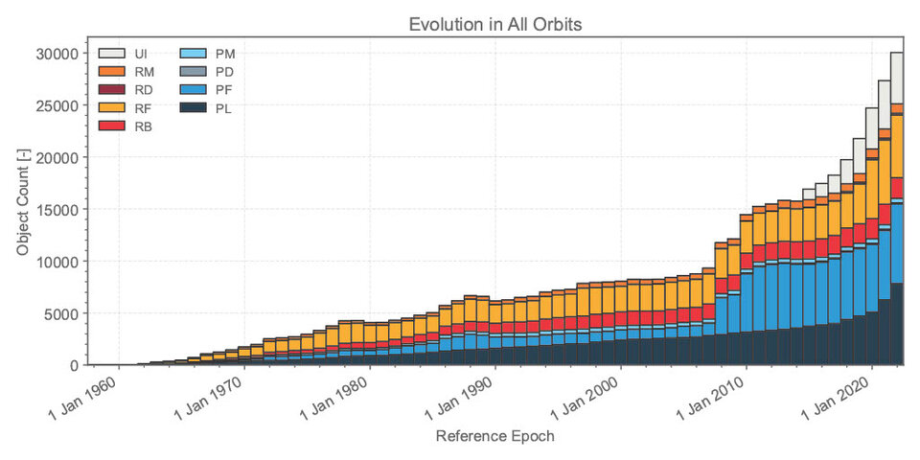

According to the data from astrophysicist and analyst Jonathan McDowell’s study Space Activities in 2022, the year 2021 saw 1829 types of various payloads delivered into orbit, primarily satellites. In 2022, this figure increased to 2500 cargoes sent to orbit.

In addition to positive trends that testify to the industry’s growth, these figures also signal an upcoming problem that humanity has yet to solve – the widespread presence of orbital debris. The main danger from the increasing number of satellite launches is that when these satellites reach the end of their operational lives, most of them remain in their previous orbit, steadily increasing the risk of collision with new spacecraft every year.

A video published by the European Space Agency (ESA) in 2019 provides a graphic visualization of debris of different diameters clogging the Earth’s orbit. The animation of space junk was created with the help of observations from the ESA IZN-1 lidar tracking station, located in the mountains of the active volcano Teide on the Spanish island of Tenerife.

McDowell’s figures also confirm official ESA data on the level of debris pollution in near-Earth orbit. According to the ESA Space Environment Report 2022,, there are currently 30,000 tracked space debris fragments in orbit,, ⅔ of which are in the prime satellite deployment territory of low Earth orbit (LEO).

In light of all the risks that these figures lay bare, Europe puts forward new advisory initiatives and legislation acts at the UN every year. Thus, in March 2023, at the 62nd session of the Office for Outer Space Affairs, there were calls for a more comprehensive exchange of information between European countries about the paths of satellites to increase the overall level of situational awareness in orbit.

Within Europe, this strategy is already working. A document on specific tools and methods for enhanced information sharing was recently presented by a number of countries, including Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Finland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. At the latest meeting of the UN Committee for the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, a compendium of standards from states and international organizations was presented for the mitigation of space debris.

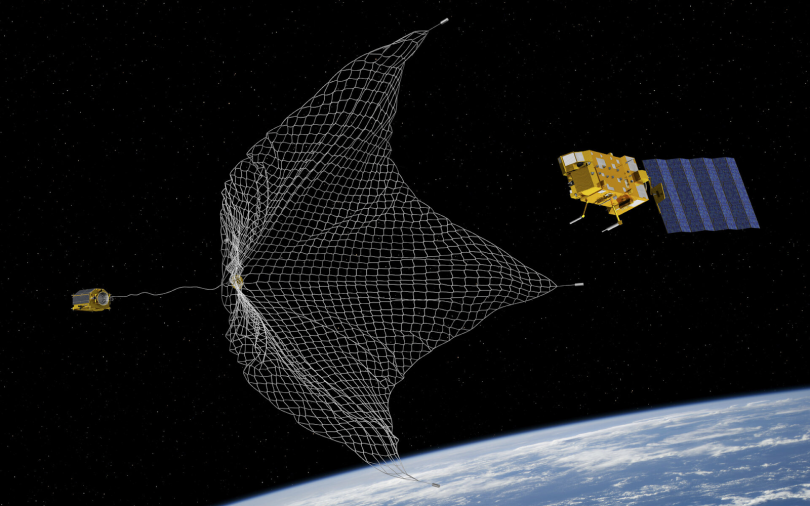

In an attempt to tackle orbital pollution, ESA has suggested carefully following the new guidance from IDAC (Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee), while continuing to adhere to the Active Debris Removal (ADR) policy. The European strategy for moderating launches and disposing of the most dangerous near-Earth objects, which has been proposed to replace the American business as usual model, is predicted by computer models to have an extremely positive effect on cleaning up orbit in the near future.

Despite all the advantages, even the most optimistic NASA and ESA models indicate that even with a sharp decrease in space launches, which seems quite unlikely in 2023, collisions in orbit will occur at least once every 10 years. Each of these unplanned encounters could spawn tens or hundreds of new fragments moving through LEO and other orbits. Even the smallest fragments, when traveling at the speeds of escape velocity, pose a mortal danger for active satellites.

In order to prioritize targets for removal, the ESA advises using the Space Sustainability Rating (SSR) index, which provides the most up-to-date information on orbital contamination based on six different criteria.

ESA offers a fairly good strategy for cleaning up orbit, but despite only being at the planning stages, it has already been mercilessly smashed against the monolith of ossified European bureaucracy. The ownership rights to certain objects, despite them no longer beinig functional, do not allow the ADR initiative to remove them from orbit without the prior agreement of their owners. These legal feuds can drag on for years, during which the orbit is being even more intensively oversaturated with expired satellites.

Another lame horse that slows down the entire team is the legal responsibility that is divided equally between the company that removes the space junk and the company that left it in orbit. In the event that a cleaning satellite which deviates from the orbit of a spent super-heavy rocket stage then causes damage to third-party satellites, the company that produced the damaged satellite will seek legal recompense.

It is worth asking at this point whether young European startups be willing venture into a a completely new field with such a high degree of legal risks. There is no way one can answer affirmatively with any certainty. But today, the legal reality in space is precisely this: the costs of junk in orbit is paid by both those who create it and those who come to clean it up.

Just don’t blow it up! The American approach

In December 2022, American legislators also took up a solution to the problem of orbital pollution. The Orbital Sustainability Act (or ORBITS Act), introduced in Congress back in September 2022, and was passed unanimously in the Senate on December 21, 2022. The law called for the allocation of $150 million for its implementation from 2023-2027.

The law would require NASA, in collaboration with the private sector and government agencies, to create a map of orbital debris which pose the greatest danger to satellites in low Earth orbit. While the ORBITS Act does not provide clear procedures for classifying and removing dangerous objects from near-Earth space, it directs NASA to open a separate program to address this issue.

The Act specifically calls on NASA to encourage and facilitate the development of technologies to remove orbital debris, and allows the space agency to bring private companies and commercial initiatives into the effort to clean up orbit. In addition to activities aimed at the direct removal of orbital debris, ORBITS will contribute to the creation of a regulatory framework to prevent future orbital debris. According to legislators, these standards will have to be updated every five years in order to best meet emerging challenges.

The bill was warmly welcomed by America’s private aerospace sector. Thus, the satellite service industry group CONFERS cheered the legislative initiative, noting that the orbital debris crisis needs to be addressed with the support of both the government and the American space industry.

The optimism of private companies somewhat overshadows an earlier study conducted by NASA’s Office of Technology, Policy, and Strategy of NASA, which points out the poor weak cost effectiveness of methods aimed at clearing orbit. The report states that these technologies recoup their costs only after 10 years of operation. Long payback periods, coupled with the costs of building orbital debris removal systems, are slowing down the influx of new investments to finance these projects.

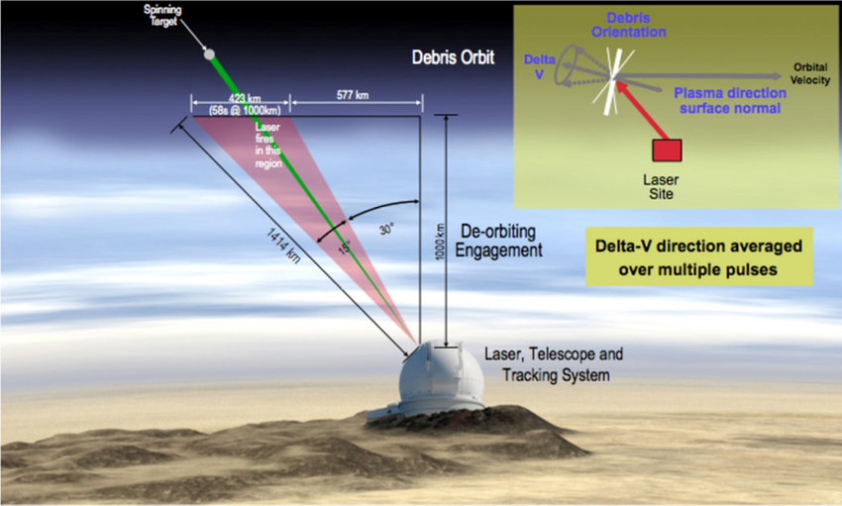

A carefully-crafted legislative framework will likely be able to stimulate growth in this sector, but even here, companies that have taken on this “dirty work” could face a number of legislative difficulties. This is particularly the case with the use of laser systems to eliminate small-diameter debris particles, as they could, when placed in orbit, be technically classified as satellite weapons. And although a NASA study concluded that the strength of these devices would be only around a thousandth as strong as they would need to be to disable satellites, the technology will remain in its infancy until there are regulations which can delineate its use.

Source: E. Victor George, Centech Corporation

Preventive measures to prevent the collision of spacecraft in orbit have drawn the attention of US lawmakers to the issue of tracking space traffic. This resulted in the Space Safety and Situational Awareness Transition Act of 2022 being introduced into the House of Representatives on December 14, 2022, but it failed to receive the necessary support. However, the bill’s authors insist that this is only the beginning of a difficult journey to create a solid legislative framework designed to solve situational awareness problems for the civilian space sector.

However, the strongest move to prevent new debris from entering orbit was made on April 18, 2022, when Vice President Kamala Harris, speaking at Vandenberg Space Force Base, announced a US initiative to completely abandon the testing of anti-satellite direct takeoff missiles (ASAT). The White House insists that its initiative does not ban countries from developing or stockpiling anti-satellite missiles, but simply asks other parties to refrain from conducting their own live tests.

A total of 16 ASAT weapon tests have been conducted by various nations to date, resulting in over 6,300 pieces of orbital debris, of which about 4,000 remain in orbit. The American initiative has unfortunately not yet received direct international approval, especially from US adversaries like Russia and China.

Bureaucracy and licensing scandals: how can we implement space law today?

It is not just orbit that is full of junk – the space industry itself also has to deal with a great deal of bureaucratic garbage. First and foremost, there have been an increasing number of scandals surrounding the issuance of licenses for space launches. There have also been quite a number of frankly unserious applications received by international bodies regulating space launches.

In October 2021, the Rwanda Space Agency (RSA) submitted an application to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to launch 327,230 satellites into space. This would be a remarkably ambitious plan for the RSA, given that at the time of its application, the country had only a single satellite, the RwaSat-1, in space launched into orbit from the ISS in 2019.

Despite its very limited experience in space, RSA chief executive Francis Ngaba has said for several years that the Rwandan initiative is an alternative to Starlink’s satellite broadband network, as the full deployment of SpaceX’s satellite constellation is constantly hampered by the protracted process of obtaining launch licenses from US regulators. The irony of this story is that, according to rumors, these slots for 300,000 satellites were being eyed for purchase by OneWeb founder Greg Weiner, and in February 2023, RSA licensed Starlink to include Rwanda in its broadband Internet coverage area.

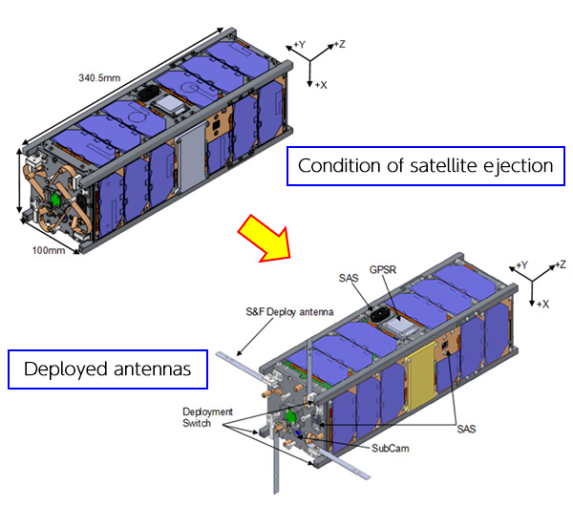

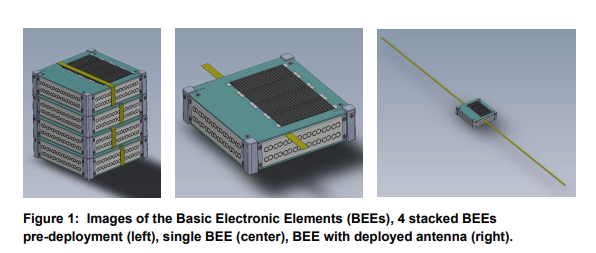

There are precedents in which certain devices have reached orbit despite not being permitted by regulatory authorities. In January 2018, the Indian launch vehicle PSLV launched a payload into orbit which included a constellation of four SpaceBEE pico satellites produced by California-based IoT startup Swarm Technologies. This may seem like just another story of a company deciding to launch satellite routers into orbit, but there was an important nuance.

A month earlier, on December 17, 2017, Swarm Technologies had received its second refusal from the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to launch four of its pico satellites. The commission considered the company’s work on resolving bugs to be insufficient, and the satellites themselves did not meet the requirements for safe operation in orbit. The SpaceBEE pico satellites’ 10×10×2.8 cm size made them too difficult to track in orbit, and if orbital objects cannot be tracked, there is a big risk that they could collide with other satellites that cross their orbit.

Source: Swarm Technologies/FCC

Despite the FCC ban, Swarm chose not to remove its satellites from the Indian rocket. Its motives are still unclear. Perhaps the company was simply naively counting on obtaining a license from the FCC at the very last moment, or perhaps it simply chose to defy the rules. The paradox of the existing Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967 is that even if the SpaceBEE’s pico satellites disappear from radar and turn into space debris, responsibility for any damage they caused will be borne by India, since it was from Indian territory that the PSLV rocket which put the satellites in orbit took off January 12. But Swarm Technologies did not go unpunished, as they were fined $900,000 after an FCC investigation. However, even in 2018, this was a relatively small price to pay for such audacity.

What lesson can we draw from the story of Swarm Technologies and the FCC? On the one hand, it testifies to the obvious “sluggishness” of regulatory procedures and the process of obtaining licenses overall. The situation is aggravated by the fact that the FCC is not an international regulator with universal jurisdiction, but rather only operates within the United States. In order to operate a space broadcast network on certain frequencies, private companies sometimes have to wait for licenses from a number of national communications agencies that regulate this activity in other countries. And the time is coming when there could be financial speculation with licenses – after all, we remember the case when the Russian State Commission on Radio Frequencies did not grant its permission to the British OneWeb, since the broadcasting frequency of British satellites was the same as that of the Russian Arctic communication station.

On the other hand, the congestion of this regulatory and legal sphere is significantly slowing down the development of the entire satellite telecommunications market today, and it is difficult to imagine when new technologies like quantum communication, which China is already testing today, will be able to make their way into this bouquet. Possible options for creating an overall international regulator for conducting space launches could somewhat simplify the situation, but this idea is rightly opposed by national regulators like the FCC and ITU, which over the years have managed to accumulate a whole base of their own regulatory and legal standards. No one is ready to allow “chaos in orbit” caused by new legal regulations.

In September 2022, the FCC agreed to the latest revision of Orbital Debris Rules, primarily aimed at improving the state of affairs in LEO. Thus, all satellites operating at altitudes of 2000 km and below should be artificially reduced from their orbit into the atmosphere no more than five years after the end of their operation (previously this period was 25 years).

It is possible that the domain of licensing permits for space missions will be able to follow a similar route. The area is now clearly lacking in flexibility, transparency, and most importantly speed in adopting the kind of approvals expected by aerospace companies.